Chapter 43 Tuberculosis in Elephants

Tuberculosis (TB) is an ancient disease of both humans and animals. Tuberculous scarring has been observed on bones from 21 of 48 mastodon skeletons recovered in North America (dating to the last Ice Age), and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from the human form of TB has been isolated from a 17,000-year-old bison bone.24 Tuberculosis and its treatment in elephants was described by Ayurvedic physicians in Asia more than 2000 years ago.28,40

A case of TB in an elephant at the London Zoo in 1875 was the first published report in modern times,17 although the archives of the European Elephant Group indicate an even earlier case in an Asian bull named “Hans” who died in 1802 from TB at Jardin des Plantes, Paris, at age 18 years.16 Numerous case reports appeared in the literature in the twentieth century.*

I examined medical records of 379 elephants from 1908 to 1992 and found only eight cases of TB.42 This retrospective study’s failure to reveal the significance of TB for elephants may be attributed to the sample population, which included elephants from Elephant Species Survival Program (SSP)–participating zoos in North America, but not privately owned elephants (from which records were not available). In addition, surveillance for TB among elephants even in zoos lacked uniformity and consisted largely of intradermal testing, now known to be inaccurate. Also, routine necropsies of elephants and evaluation of ill elephants for the presence of TB were not performed.

The year 1996 is often heralded as the date that TB “emerged” as a disease of concern for elephants, with outbreaks of TB in elephants in North America.4,43,44 Subsequent outbreaks in Europe have since been reported.18,34,45

DEFINITION

Tuberculosis is caused by bacteria in the genus Mycobacterium, which comprises more than 100 species. Mycobacteria infect a broad range of species, including humans, nonhuman primates, domestic and nondomestic ungulates and carnivores, marine mammals, psittacine birds, reptiles, and fish. Species susceptibility to specific mycobacteria varies.46

The term mycobacteriosis describes disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), also called “atypical mycobacteria” or “mycobacteria other than TB” (MOTT). Most NTM are saprophytes found in soil or water, but they may occasionally cause disease in humans and animals. Mycobacterium elephantis, a rapidly growing, newly described mycobacterium, was isolated from a lung abscess of an elephant that died of chronic respiratory disease.61 This same organism was isolated from 10 human sputum samples and one human lymph node specimen in Canada; however, there was no epidemiologic link between these reports.63

ETIOLOGY

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tb) is the predominant disease-causing agent in elephants, although TB cases have been caused by M. bovis. Mycobacterium szulgai, an uncommon NTM species, has been associated with fatal disease in two African elephants.30 Mycobacterium avium is often isolated from elephants50 but has not been associated with clinical disease.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Frequency and Distribution

Both African and Asian elephants are susceptible to TB. I am aware of 34 known cases of TB affecting 31 Asian and 3 African elephants in the United States between 1994 and 2005.15 Five cases were reported in Europe in 2002,34 with two subsequent cases in 2005.45 More frequent reporting of the disease in Asian but not African elephants may reflect closer human contact related to the use of Asian elephants for performances and rides. Likewise, the vast majority of cases occurring in female elephants may be a result of their higher number in captivity and the greater likelihood of human contact with cows than bulls. The disease occurs in captive elephants in Asia as well.6–10,47,54,55 There are no reports to date of TB in wild elephants.

Reservoirs

The reservoirs for M. tb and M. bovis are infected humans and cattle, respectively.25 Transmission may occur via respiratory or alimentary routes. Feces, urine, genital discharges, milk, and feed or water may contain contaminated droplets. In elephants, M. tb has been isolated from respiratory secretions, trunk washes, feces, and vaginal discharges. The M. avium-intracellulare group can survive in the environment and, unlike the M. tb– complex group, does not need a host to survive. Thus, infection is not always acquired from another infected animal. Clinical disease in elephants from M. avium has not been reported.

PATHOGENESIS

Infection versus Disease

Infection with mycobacterial organisms does not necessarily imply active disease. Several possible scenarios may result after exposure to an infectious source (Table 43-1). Tuberculosis is estimated to infect latently one third of the global human population and causes approximately 3 million deaths yearly. Latent TB infection (LTBI) in humans is characterized by a positive intradermal test but a lack of clinical disease and no evidence of active shedding of live bacilli. In LTBI, bacterial organisms are sequestered but may reactivate at a later date. Individuals with LTBI are a reservoir for future active cases, and although only an estimated 4% to 10% of latently infected humans with normal immune status will develop active TB during their lifetime, the identification and treatment of individuals with LTBI and at high risk for activation remain an effective means of control.48

Table 43-1 Possible Scenarios after Exposure to Active Tuberculosis (TB)

| Scenario | Pathogenesis | Tuberculin Skin Test Status (In Humans) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | All bacteria are killed, and no disease results. | Negative |

| 2 | Bacteria multiply, and clinical disease results (primary TB). | Positive |

| 3 | Bacteria become dormant and never cause disease (latent TB). | Positive |

| 4 | Latent organisms reactivate and cause active disease. | Positive |

Host Immunity

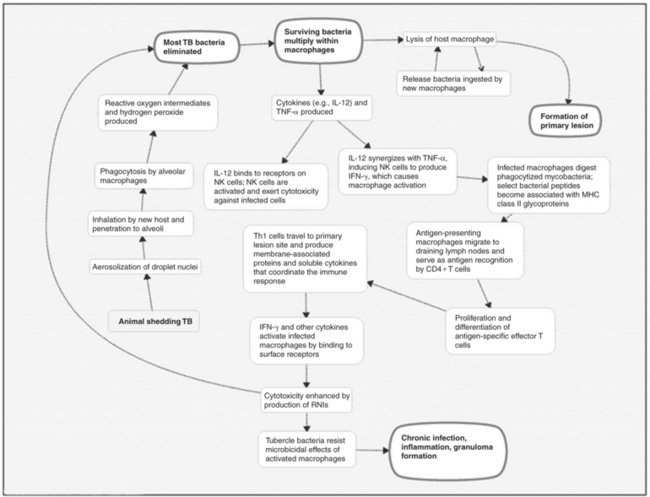

The immune response to TB infection is both cell mediated and humoral. A comprehensive discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter, but Figure 43-1 presents a basic outline. For further details, see Schulger and Rom,59 Salgame,57 and Boomershine and Zwilling5 or current immunology texts.

CLINICAL SIGNS

Tuberculosis is characteristically a chronic wasting disease; thus the term “consumption” was used to describe the disease in humans in the early twentieth century. Signs in elephants may include weight loss, wasting, and weakness.22,40,44,58 Coughing or dyspnea have been reported53,56,60 but appear to be uncommon. Exercise intolerance may be noted in working elephants. Ventral edema has been reported, but other pathologic factors may have been the inciting cause.53,60 In many cases, clinical signs are absent. Of the 34 cases mentioned earlier, 12 were asymptomatic and diagnosed postmortem. In some of these cases, TB was considered an incidental finding. Elephants that show wasting antemortem will have advanced and possibly disseminated disease on postmortem examination.

DIAGNOSIS

Antemortem Tests

The reader should consult the most current online version of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Guidelines for the Control of Tuberculosis in Elephants.64

Direct Tests

Acid-Fast Bacteria Stain.

Mycobacteria do not readily accept Gram’s stain but may be detected by acid-fast bacteria (AFB) stains such as Ziehl-Neelsen. A positive AFB trunk wash smear is suggestive of TB but not definitive because other organisms (e.g.,Nocardia) are also acid-fast. In general, acid-fast staining has low sensitivity (50% in humans) and is nonspecific, particularly in geographic areas where NTM are typically isolated.11

Culture.

Isolation of mycobacterial organisms is the method identified in the 2003 Guidelines64 to establish a definitive diagnosis of TB in elephants. A trunk wash technique is used in which (1) approximately 60 mL of sterile saline is instilled into the trunk, (2) the trunk is elevated for 20 to 30 seconds, (3) the trunk is lowered into a zippered plastic bag, (4) the elephant is told to forcibly exhale (the usual command is “blow”), and (5) the sample is transferred to a secure screw-top tube for submission to the laboratory. Samples should be sent only to laboratories capable of culturing mycobacteria. Three samples collected on separate days within 7 days are required. The Guidelines64 include a detailed description of the procedure, or see Isaza and Ketz.26 Elephants must be trained to accept the procedure.

Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques.

The MTD has a rapid turnaround time (2.5-3.5 hours) and can detect low numbers of organisms. In smear-positive patients, the MTD is comparable to culture with BACTEC 460, and both tests demonstrate a sensitivity and specificity of about 96%. In smear-negative patients, the sensitivity is 72% and the specificity 99%. In one study the MTD was positive on 14 elephants from which M. tb or M. bovis was cultured, positive on 15 elephants from which TB was not isolated, and negative on 6 culture-positive elephants.50 A positive MTD and negative culture result may represent infection with low-level shedding below the detection capabilities of culture or nonviable organisms. Failure of the MTD to detect the 6 culture-positive elephants may be explained by improper specimen collection and transport, specimen sampling variability, laboratory procedural errors, inhibitors, sample misidentification, or transcriptional errors. (The test is not validated for elephants and never will be.) Further research is needed.

A PCR technique is under investigation to detect mycobacterial organisms in trunk wash samples. Experimentally, this PCR has detected very small numbers of mycobacteria using M. bovis–spiked trunk washes, but further work is needed to better determine test sensitivity and specificity.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree