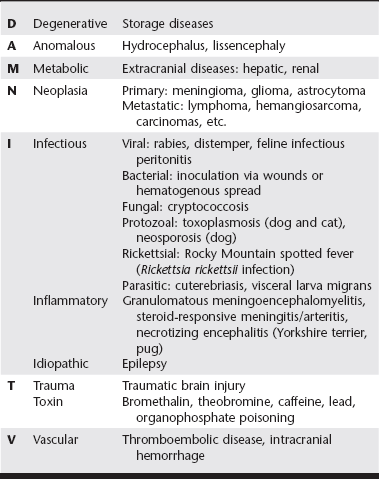

Chapter 230 Once extracranial causes of seizure are ruled out, the many primary intracranial causes of seizure must be considered. In patients with localizing neurologic deficits (e.g., cranial nerve dysfunction or lateralized proprioceptive deficits), intracranial disease is more likely than extracranial disease. A classification scheme such as DAMNIT-V can be helpful for organizing this large list of disorders. See Table 230-1 for a compilation of differential diagnoses using the DAMNIT-V scheme. Definitive diagnosis of intracranial causes of seizure commonly requires advanced imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography and cerebrospinal fluid analysis, which usually cannot be done until the patient is in stable condition and seizures are controlled. Basic historical and signalment data can be useful in ranking the relative likelihood of each of the differential diagnoses. In dogs younger than 6 months of age, infectious or anomalous diseases are most common. In dogs between 6 months and 6 years of age, idiopathic epilepsy is most common, and in dogs older than 6 years of age, neoplasia is most likely. In younger cats, infectious and anomalous diseases are most common. In outdoor cats, parasitic diseases like cuterebriasis should be considered, and in catteries and multicat households, feline infectious peritonitis becomes more likely.

Treatment of Cluster Seizures and Status Epilepticus

Differential Diagnoses and Diagnostic Workup

Intracranial Causes of Seizure

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine