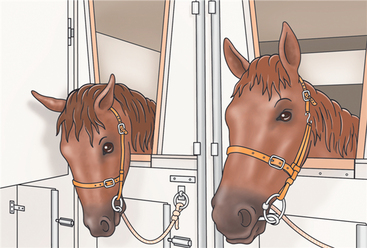

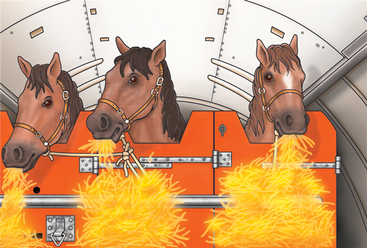

CHAPTER 10 Horses have been transported from place to place for thousands of years, with records indicating that this species was moved by sea up to 3500 years ago. Horses were “caged” and usually held below deck. Even in these early times, transport resulted in the increased death rates of those horses transported below deck. In contrast, those shipped on deck generally experienced better health (Hayes, 1902). The difference was ascribed to better air quality on deck than below. By the 1800s horses were transported in horse-drawn vans, followed by rail transport in the mid-late 1800s (Creiger, 1989). This became the major mode of cross-country transport until the 1950s, although it was found that some horses travelled better than others. Therefore, it often has been assumed that transporting horses by road, sea, or air was inherently stressful. Over the recent decades, the stress arising during transport has been a subject that has attracted much more interest than in the past (Creiger, 1982). Appreciating the problems inherent in transport requires “hands on” experience. This can be difficult to obtain because transport companies are highly specialized and have little room in a competitive commercial environment for well-intentioned amateurs. Indeed, these companies retain a highly skilled cadre of individuals (grooms) who routinely participate in the transportation of horses. As a consequence of this, many people (including a significant proportion of those intimately involved with the horse industry for many years) have a very limited understanding of the horse transport industry (Leadon, 1973; Leadon, 1999; Marlin, 2004). An understanding of this industry and its inherent problems is essential, given the prevalence of national as well as international trade and competition of horses that exists today. For example, it is common for horses in Europe and the United Kingdom to venture to the Breeders Cup in the United States, the Japan Cup, and to Hong Kong and the Magic Millions or Melbourne Cup carnivals (Australia) and other invitational races. Additionally, horses are routinely transported to the Olympic Games and World Equestrian Games and numerous similar sporting events (Leadon, 1999; Marlin, 2004) This chapter outlines the evolution of the horse transport industry and describes some of its current practices, with particular reference to air transportation. Potential sources of stress within the transport environment are then identified, and methods of quantifying the severity of these stressors are discussed (McCarthy et al., 1990). The transport of horses necessitates their being limited to a restricted space. This confinement brings with it inherent problems in ensuring effective respiratory function (particularly, appropriate functioning of the mucociliary escalator), as well as heat dissipation and ventilation, which, if not dealt with properly, can result in a variety of adverse outcomes for the horse (Copas, 2011; Rackyleft and Love, 1989). One of the most serious is the rapid development of “shipping fever,” or pneumonia or pleuropneumonia. Thus, appropriate management and veterinary care prior to, during, and after transport can help reduce the prevalence and severity of shipping fever. Therefore, the chapter concludes with a series of recommendations to horse owners and veterinarians, with the aim of optimizing the health of horses during transport (Leadon, 1999). Land transport of the horse may have had its origins in the eighteenth century. There are various reports of the carriage of horses in custom-built horseboxes. During the reign of Queen Anne in England (1702–1714), a horse may have been carried in this way, either for a bet or to transport it to a race meeting without “tiring it.” This development was accelerated by the transport of Elis, the subsequent winner of the English St. Leger, by road in 1836 (Leaden, 1973). This horse was transported several hundred miles from his home stabling to the racecourse faster than he could have traveled by being led or ridden, which was the usual custom. Massive gambling wagers were undertaken as a result of this innovation. Rail transportation became the vogue from the 1850s till the 1950s, particularly for long-distance movements. Motor vehicles were used between the 1920s and the 1950s for short-distance journeys. This form of transportation replaced rail carriage in the 1950s with the progressive evolution of sophisticated vehicles over the decades (Creiger, 1989). There are limited statistics that reflect the traveling activities of the competition horse industry. In excess of 250 events that represent the elite sector of the equestrian disciplines, are held in Europe each year under the auspices of the Federation Equestre Internationale (FEI, 2012). Worldwide, the FEI sanctions more than 1200 events on all continents. Thus, on the basis of an average of at least 100 horses entered in the elite FEI-sanctioned events in Europe, this would involve more than 250,000 movements of horses for these purposes alone. It is hard to estimate the number of horse movements related to all shows or competitions for horses on an annual basis, but it appears likely that this number could be in the millions. These estimates reflect the overall extent of these activities, which, by definition, must be accompanied by the movement of horses. The racing industry in the United Kingdom documents over 9500 races per annum with approximately 92,000 starters in these races. Similar figures for Ireland show about 2400 races annually with approximately 30,000 runners. Again, this will represent a very substantial number of horse movements in this sector (Racing Post, 2012). The true size of involvement of the air transport industry in the shipment of horses is also impossible to quantify with certainty, but many horses are transported by air. Common routes for horses to travel are from the United States to Europe, the United Kingdom, or Ireland; from South America to the United States or Europe; from the United States, Europe, the United Kingdom, Ireland, or South America to the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and the Antipodes. In the period of the massive increase in investment that occurred in the bloodstock industry in the 1980s, the activities of one Irish-based cargo airline, Aer Turas, were devoted almost entirely to the transport of more than 8000 horses by air annually. These 8000 horses were mostly those traveling between the “tripartite countries,” that is, Ireland, the United Kingdom, and France. Currently, major international carriers, such as KLM, Lufthansa, and Polar, to name but three, are carrying more than 10,000 horses each year. For example, KLM cargo has 85 dedicated horse stalls for the transportation of horses in the cargo bay of their “heavy” jets (KLM, 2012). Market forces greatly influence these totals, as may be evidenced by the profound decrease in the importation of horses by air from Europe into Australia totaling more than 800 in the mid-1980s to less than 100 in 1991 (Wallace, personal communication). Similar changes have accompanied the global financial crisis of 2007 with a resultant dramatic change in the profile of horse transportation by air. However, with the progressive increase in sport horses being transported over long distances by air, the effect of the downturn has not been as profound as occurred in the early 1990s. Athletic horses may be carried either in trailers (floats) or in modified vans. In Europe, trailers, or “floats,” are usually designed to carry two or three horses, but in the United States, similar trailers can carry six, nine, or even more horses. The chassis of heavy-goods trucks are often combined with purpose-built coachwork to provide individual stall accommodations for valuable athletic horses (Figure 10-1). These vehicles may vary considerably in appearance, internal volume, and layout. They are usually designed to carry four, six, or nine horses. There is accommodation for “grooms” (trained professional horse handlers) to travel with these horses, usually in the ratio of one groom to up to nine horses. The individual access to horses that is afforded by the vehicle design allows for the provision of food and water for the horses while the vehicle is moving. Food, in the form of hay and water, is often provided at least every 4 hours, with many variations, depending on individual cases. Journey durations can vary from a few hours to several days. The usual practice within this elite sector of the horse transport industry is for overnight rest in stables to be provided after every 24 hours of transport. Air transport of horses utilizes either a jet-stall system, in which horses travel in a fully enclosed “air stable,” or an open-stall system (Figure 10-2), in which there is a lesser degree of enclosure. The open stall system is usually utilized when the entire aircraft (which would be a freighter type in configuration) or a considerable section of it has been chartered by a horse transport agency. Today, nearly all commercial transportation involves use of jet stalls, as these restrict the movement of horses and also minimize the amount of space taken by each animal in the cargo bay. These stalls measure 294 cm (117”) long, 234 cm (93.6”) wide, and 232 cm (92.8”) high, with the horse floor space being 188 cm (75.2”) by 234 cm (93.6”). In a three-horse configuration, each horse has 75 cm (30”), with this being approximately 50% in a two-horse configuration. The numbers of horses that are carried in open-stall systems is determined by the type of aircraft in which they are carried and the sizes of the horses to be transported. Three horses can be accommodated across the width of a narrow-bodied airplane (e.g., a Boeing 727-200) in triple stalls. This number can be extended to four horses, provided they are relatively narrow in conformation, in quad stalls. Wide-bodied jets (e.g., a Douglas MD-11 and Boeing 747, the latter being the most common vehicle for carrying horses by air) can accommodate up to seven horses across their width. The normal practice of the horse air transport industry is that the ideal personnel-to-animal ratio should be one groom for every three horses on the airplane. However, this ideal is not always attainable because of the restricted number of seats available on some aircraft. Horses are usually offered hay ad libitum while the aircraft is in flight, and water is usually offered regularly (maximally every 6 hours) and following landing and during refueling stops (Leadon 1999; Marlin, 2004).

Transport of horses

History of the transport of performance horses

Size of the present-day horse transport industry

Air

Current methods of transport of athletic horses

Air

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree