Chapter 105Track Surfaces and Lameness

Epidemiological Aspects of Racehorse Injury

Racing Surfaces

The Risk of Injury on Different Racing Surfaces

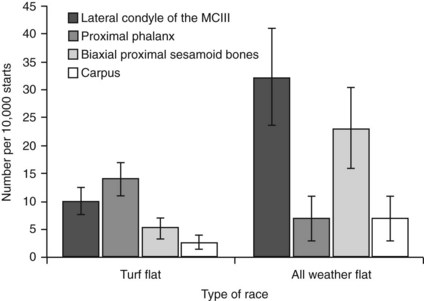

Fractures predominate as a major type of injury, and the bones distal to the carpus or tarsus are most often affected.3,4 Postmortem investigations conducted in the United Kingdom have enabled estimates of the risk of different types of fracture on different racing surfaces (Figure 105-1).8 The overall incidence of catastrophic distal limb fractures in all-weather flat races was 0.74 per 1000 starts compared with 0.37 per 1000 starts in turf flat races. In other words, the relative risk (RR) of catastrophic distal limb fracture on all-weather surfaces compared with turf was 2.0 (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.3 to 3.1). There were also significant differences in the risk of certain types of fracture on these surfaces. In particular, fractures of the lateral condyle of the third metacarpal bone (McIII) were 3.2 times (95% CI 1.6 to 6.6) more likely to occur on all-weather surfaces than turf racecourses, and biaxial proximal sesamoid bone (PSB) fractures were 4.6 times (95% CI 1.8 to 11.6) more likely to occur on all-weather surfaces than turf racecourses.8 Some fracture types were more common on the turf. For example, catastrophic fractures of the proximal phalanx were twice as common (RR 2.0; 95% CI 0.6 to 6.7) on turf than on all-weather surfaces.8

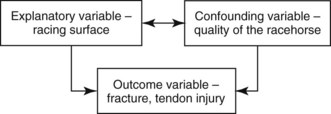

Even within a racing jurisdiction, direct comparisons between turf and all-weather tracks should not be made without consideration of all potential explanatory factors. For example, in the United Kingdom the prize money available and class of flat race held on the all-weather racecourses are generally lower than for flat races held on turf. This is obviously potentially an important confounding factor, as one of the reasons for poor performance may be subclinical or previous injury. It is therefore possible that horses in all-weather flat races are inherently more likely to sustain an injury, regardless of the surface on which they are racing. The type of surface may be important, but it is imperative to consider all potential factors in the same analysis. In order to deal with confounding variables, epidemiologists build multivariable or multiple regression models. These models adjust the size of effect and significance of risk factors by accounting for the effect of other confounding variables that are associated with both the outcome and other explanatory variables (Figure 105-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree