Chapter 116Lameness in the Dressage Horse

The Sport

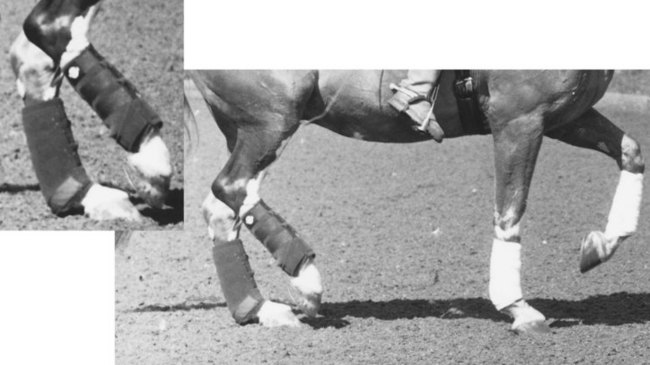

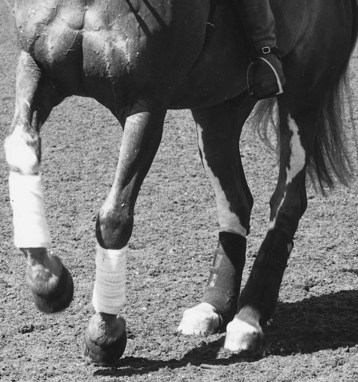

In Europe the competitive sport has been divided into three levels: L, M, and S. L covers novice level (novice and elementary); M covers medium and advanced medium; and S covers Prix St Georges, Intermediare I and II, Grand Prix, and Grand Prix Special. The movements required at each of these levels reflect the horse’s degree of collection, with the L classes expressing balance and freedom of movement, M classes requiring more collection and lateral movements, and S classes demanding ultimate collection to enable movements of maximum collection and suspension, such as piaffe, passage (Figure 116-1), and canter pirouettes (Figure 116-2). However, even the most skilled rider or trainer has difficulty selecting the right horses, because many promising young horses with excellent gaits fail to learn passage and piaffe, probably because of our insufficient knowledge of the biokinematics of collection.1