Chapter 158 Thermal Burn Injury

INTRODUCTION

Thermal burn wounds are relatively uncommon in veterinary medicine. The most common sources of burns in small animals include electric heating pads, fire exposures, scalding water, stove tops, radiators, heat lamps, automobile mufflers, improperly grounded electrocautery units, and radiation therapy.1 Most burn wounds can be managed the same as traumatic wounds (see Chapter 157, Wound Management). Like traumatic wounds, burn wounds can be labor intensive and expensive for the owner. In addition, numerous metabolic derangements can adversely affect the patient, prolong hospitalization, and complicate the recovery.

DEFINITIONS

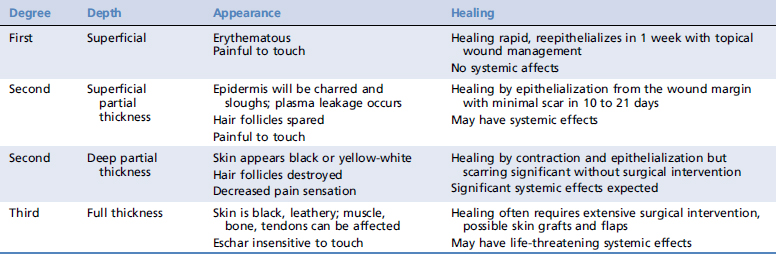

Although these are now considered older terms, many physicians still like to refer to burn wounds as first-degree, second-degree, and third-degree injuries (Table 158-1).1,2 First-degree burn wounds are superficial and are confined to the outermost layer of the epidermis. The skin will be reddened, dry, and painful to touch.

Patients with burns involing more than 20% of their total body surface area (TBSA) can have serious metabolic derangements. Patients with more than 50% of their TBSA involved have a poor prognosis, and euthanasia should be discussed with the owners as a humane alternative. TBSA can be estimated in animals using percentages allotted to body area using the rule of nines as described in Table 158-2.1-3

Table 158-2 Estimating Total Body Surface Area Burned

| Area | Percentage (%) | Total % |

|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 9 | 9 |

| Each forelimb | 9 | 18 |

| Each rear limb | 18 | 36 |

| Thorax | 18 | 18 |

| Abdomen | 18 | 18 |

| TOTAL | 72 | 99 |

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

The patient should be assessed immediately for airway, breathing, and circulatory compromise as for all trauma patients (see Chapter 2, Patient Triage). Following a full physical examination, including inspection of the patient from head to foot pads, an assessment of the degree and TBSA of the burn wounds should be performed to help determine prognosis and the extent of treatment necessary. Blood should be collected for evaluation of packed cell volume, total solid and electrolyte levels, and blood gas parameters, minimally.

Metabolic Derangements

Fluid losses can result in hypovolemic shock (see Chapter 65, Shock Fluids and Fluid Challenge). After initial shock resuscitation with isotonic crystalloids up to 90 ml/kg IV in dogs (50 ml/kg in cats) and synthetic colloids or blood products, if needed, total fluid delivery rate during the first 24 hours should be 1 to 4 ml/kg body weight × % TBSA burned.2 After 12 to 24 hours, when vascular permeability is stabilized, a constant rate infusion (CRI) of synthetic colloids (e.g.,hydroxyethyl starch, dextran-70) may be beneficial at a rate of 20 to 40 ml/kg/day. Plasma is given at 0.5 ml/kg body weight × % TBSA burned in humans, although this has not been investigated in dogs and cats. By 48 hours after injury, plasma volume is mostly restored, and thus patients are at high risk for generalized edema and fluid overload from the high initial demands for fluid replacement.3 Ideally, fluid therapy should be adjusted for the individual patient based on cardiovascular stability, central venous pressure (0 to 10 cm H2O), and urine output (>1 ml/kg/hr).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree