Chapter 8 Theriogenology of Sheep and Goats

Sheep and goats are very fertile animals, with reproductive potential far superior to that of most other domestic animals. Specific assessment of the reproductive system should always be preceded by a complete physical examination to determine general health status and to detect problems that warrant therapeutic or management intervention (see Chapter 1). Animals need to be productive (i.e., healthy) before they are able to be reproductive—in other words, sex is a luxury. Of relevance in this context, a single range ewe usually does not undergo the same sort of reproductive manipulation or physiologic stress as that typical for a donor used in an embryo transfer (ET) program.

Male Reproduction

Anatomy and Physiology of the Male

The anatomy of the reproductive organs of the ram and buck is similar to that of other ruminants. The penile urethra is surrounded by the corpus spongiosum penis (CSP) throughout its length. The urethra terminates as a vermiform appendage. Blood enters the CSP proximally and exits through two exhaust veins located on the free portion of the penis. Contractions of the urethralis and bulbospongiosus muscles force blood rhythmically through the CSP, producing the characteristic pulses of urine observed during normal micturition. The most prominent structure of the penis is the corpus cavernosum penis (CCP). It consists of cavernous space supported by fibrous trabeculae. This cavernous tissue is located on the dorsal surface and partially surrounds the CSP. At its origin in the pelvis the CCP is composed of two crura that join before leaving the pelvis. The entire penis is surrounded by the tunica albuginea. The two paired retractor penis muscles arise from the coccygeal vertebrae and pass around the anus to become two distinct muscles that attach to the ventrolateral surface of the penis at the distal bend of the sigmoid flexure. The penis normally is held in an S-shaped bend (the sigmoid flexure) except during erection and ejaculation by the retractor penis muscles.1

The testicles are suspended away from the body within the pendulous scrotum. The scrotum is composed of undulating epidermis that may or may not be covered by wool or hair, depending on the breed and husbandry practices. A rich plexus of blood vessels, lymphatics, and sweat glands lies beneath the skin. The dartos, a smooth muscle layer, is connected to the vaginal tunics of the testicle by the scrotal fascia. The scrotal fascia is the connective tissue that typically is broken down in separation of the skin from the testicle during routine castration. The vaginal tunics are outcroppings of the peritoneum and form a protective covering over the testicles. The space between the two layers of vaginal tunic (parietal and visceral) as it reflects around the testicle normally contains a small amount of peritoneal fluid. The scrotal septum, composed primarily of the dartos muscle, divides the scrotum into two halves.2

The testicle itself is surrounded by a thick layer of fibrous connective tissue known as the tunica albuginea. The parenchyma of the testicle is composed of seminiferous tubules that contain the germ cells and their supporting cells (Sertoli cells). The seminiferous tubules drain into the rete testes, which in turn is drained by 10 to 12 efferent ducts. These ducts drain into the head of the epididymis, which is located on the dorsal craniolateral aspect of the testicle. The body of the epididymis curves around the lateral portion of the testes and ends caudomedially as the tail. The tubular structure is reflected dorsally and becomes the vas deferens.2 Rams and bucks have a full complement of accessory sex glands. The small bulbourethral glands are located caudally in the pelvic cavity on either side of the pelvic urethra and can be palpated rectally. These animals also have lobulated vesicular glands, disseminate prostates, and a widening of the vas deferens known as the ampulla.3 Spermatogenesis requires approximately 49 to 60 days from the start of germ cell division until the spermatozoa are released from the seminiferous tubules. Another 10 days to 2 weeks are required for the sperm to pass from the seminiferous tubules through the epididymis.4

Puberty and Seasonality

Ram

Puberty typically occurs in the ram at 6 months. It is defined as the point at which the ram develops an interest in sexual activity and produces spermatozoa in sufficient numbers to achieve pregnancy in ewes. The exact age at puberty depends somewhat on breed and time of birth. Rams born early in the spring are older at puberty than late-born lambs. Moreover, rams that are periodically exposed to cycling ewes tend to reach puberty earlier.5 Rams are seasonal breeders: Sperm quality, daily sperm output, and sexual activity are modulated by the increased periods of darkness that are typical of fall (in the Northern Hemisphere). This seasonality in the ram also is manifested by an increase in the testicular circumference (by approximately 1 to 2 cm). The increase in melatonin, which is secreted from the pineal gland during the dark hours as day length shortens, is responsible for many of the physiologic mechanisms associated with transition of the ram from the nonbreeding to the breeding season.6 Manipulation of light-dark intervals and the use of melatonin can alter the breeding season of rams, but the practicality of these procedures is debatable.7

A change in the sexual attitude of the ram toward the ewe as day length decreases defines the onset of the breeding season. He becomes more sexually interested in the female, and courtship behavior occurs more frequently. Rams display a typical flehmen response to females in estrus after sniffing the vulva region and urine from the estrus female. The ram often strikes out at the female with one front leg before mounting her.6

Buck

Breed, age, and nutrition contribute to the onset of sexual maturity in the buck.8 The age at puberty depends on the breed, ranging from 2 to 3 months in pygmy breeds to 4 to 5 months in Nubian and Boer bucks. In most breeds of goats raised in the temperate environment of the Northern Hemisphere, sperm is present in the ejaculate at 4 to 5 months. At this age, however, semen quality is poor, and the animals are not suitable for breeding.9 Nubian and Boer bucks begin exhibiting libido behaviors at 10 to 12 weeks and start producing good-quality semen at approximately 8 months.8,9

Natural adhesions of the urethral process and glans penis to the prepuce make the immature buck incapable of copulation. This attachment begins to separate at 3 months, and fertile mating is possible at 4 to 5 months.8,9 Fast-growing, well-fed, and well-managed kids are able to breed sooner than starved males of the same age.

Outside the normal breeding season, many bucks have depressed libido, reduced pheromones, decreased scrotal circumference (SC), lower rates of viability of spermatozoa after freezing, and a larger number of abnormal spermatozoa. All of these changes reflect lower levels of LH and testosterone. LH and testosterone concentration, libido, and odor presence in the buck peaks in the fall.10,11 Sexual behavior of the buck includes actively seeking does in estrus, courtship (kicking, pawing, muzzling, grunting, and flehmen), mounting, intromission, and ejaculation. Ejaculation occurs spontaneously and is characterized by a strong pelvic thrust with a rapid backward movement of the head.9 After ejaculation, the buck dismounts and shows no sexual arousal for a few minutes to several hours.

1. Beckett S.D., Wolfe D.F. Anatomy of the penis, prepuce, and sheath. In Wolfe D.F., Moll H.D., editors: Large animal urogenital surgery, ed 2, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1998.

2. Heath A.M., Purohit R.C. Anatomy of the scrotum, testes, epididymis, and spermatic cord (bulls, rams, and bucks). In Wolfe D.F., Moll H.D., editors: Large animal urogenital surgery, ed 2, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1998.

3. Ashdown R.R., Hancock J.L. Functional anatomy of male reproduction. In Hafez E.S.E., editor: Reproduction in farm animals, ed 4, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1980.

4. Pineda M.H., Faulkner L.C. The biology of sex. In McDonald L.E., editor: Veterinary endocrinology and reproduction, ed 3, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1980.

5. Price E.O., Borgwardt R., Dally M.R. Heterosexual experience differentially affects the expression of sexual behavior in 6- and 8-month old ram lambs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1996;46:193.

6. Fitzgerald J., Morgan G. Reproductive physiology of the ram. In Youngquist R.S., Threlfall W., editors: Current therapy in large animal theriogenology, ed 2, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2007.

7. Nett T.M. Controlling seasonal reproduction: emphasis on the male, Proceedings Annual Conference of the of the Society for Theriogenology. Nashville: Tenn; 1991.

8. Smith M.C., Sherman D.M. Goat medicine. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1994.

9. Goyal H.O., Memon M.A. Clinical reproductive anatomy and physiology of the buck. In Youngquist R.S., Threlfall W.R., editors: Current therapy in large animal theriogenology, ed 2, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2007.

10. Hill J. Goat reproductive management, Proceedings of the Symposium on Health and Diseases of Small Ruminants. In American Association of Small Ruminant Practitioners. Nashville: Tenn; 1996.

11. Wilddeus S. Reproductive management for meat goat production, Proceedings of the Southeast Region Meat Goat Producers Symposium. Tallahassee, Fla: Florida A & M University Press; 1998.

Breeding Soundness Examination in the Ram

Physical Examination

A complete physical examination should be performed on all rams. The ram can be restrained by placing him on his rump in a sitting position1–11 (see Chapter 1).

Examination of Reproductive Tract

The scrotum should be palpated to ensure that both testicles are present, approximately equal in size, and of firm consistency; any localized swellings or areas of induration should be noted. The head and tail of the epididymis is palpated to detect swelling, pain, or signs of inflammation. Epididymitis is a relatively common problem in rams. Any ram exhibiting signs of epididymitis should be considered to be infected with Brucella ovis until proved otherwise. The spermatic cord should be examined specifically for deformities in the vascular plexus and vas deferens. The penis usually can be extended by pressing down around the external preputial orifice and grasping the protruding penis with a gauze pad (Figure 8-1). Occasionally the sigmoid flexure may need to be straightened to assist in extending the penis. The penis is then carefully inspected for evidence of active lesions or old scars. The penis can be held in extension by wrapping a strip of gauze around the junction between the free portion of the penis and the prepuce. This method also is helpful in collecting semen by electroejaculation. The penis generally is easier to extend when the animal is being held up on the rump than when it is in lateral recumbency.

Scrotal Circumference

To determine the SC, the clinician should pull both of the ram’s testicles ventrally into the scrotum and measure it at its largest circumference, using a tape measure marked in centimeters. Care must be taken with breeds that have heavy scrotal wool, because wool may falsely enlarge the measured circumference. Taking the average of several measurements can increase the accuracy of the SC value obtained. The tape should be snug on the scrotum, while barely indenting the skin, so that the tape does not slide out of position (Figure 8-2). SC in the ram is highly heritable and appears to be related to sperm output and age at puberty.1,2

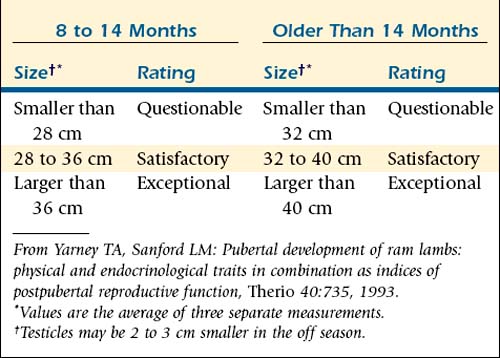

For selection of ram lambs, the testicular diameter at 170 days provides a long-range prediction of postpubertal testicular size and sperm output.3–5 SC is a major criterion for selecting replacement rams. Minimum accepted SCs of 30 cm for ram lambs weighing more than 150 lb, 33 cm for 12- to 18-month-old rams, and 36 cm for rams weighing more than 250 lb have been suggested.1 Strictly on the basis of age, rams at 8 to 14 months should have SCs of 28 to 36 cm to be classified as satisfactory and more than 36 cm to be classified as exceptional. Rams older than 14 months should have SCs of 32 to 40 cm to be classified as satisfactory and more than 40 cm to be classified as exceptional.10

Scrotal size usually is greatest from August to October. Smaller testicular measurements (0.5 to 1.5 cm less) are to be expected when rams are tested outside of the normal breeding season (February to April) or during periods of extreme sexual activity.1,2 (Table 8-1)

Semen Collection

The penis is extended as described previously. The ram is then placed in lateral recumbency to collect semen by electroejaculation. The same electroejaculators described for use in bucks are used for rams (Figure 8-3). The clinician inserts the tip of the ram’s penis and the urethral process into the warmed glass or plastic tube. Some rams ejaculate at this point of the examination. The rectum is cleared of feces and a lubricated electric rectal probe is carefully inserted. The clinician massages the accessory sex glands by moving the probe back and forth in a cranial to caudal direction 8 to 10 times while gently forcing the tip of the probe ventrally. Mild electrical stimulation is then applied for 5 seconds. The ram typically vocalizes during this procedure and attempts to escape. After the ram relaxes, the massage and electrical stimulation are repeated until the ram ejaculates into the tube. The spiraled urethral process straightens during the ejaculatory process. The collected semen is evaluated for sperm motility and morphology and the presence of inflammatory cells.2,11

Semen Evaluation

Sperm Motility

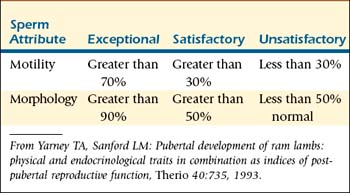

A drop of raw semen is first examined under low power (100×) to estimate the concentration and motility of spermatozoa. A drop of warmed saline is placed on the slide. The clinician then dips the corner of a coverslip into the drop of raw semen and mixes it with the drop of warmed saline. The resultant mixture should allow observation of the motion of individual spermatozoa. If the semen mixture is too concentrated to allow identification of individual spermatozoa, a new preparation should be made with less semen. With experience, the observer will be able to determine the amount of semen to place on the coverslip to make an adequate slide. The examiner should visually estimate the number of progressively motile sperm. A common error is to overestimate the percentage of progressively motile sperm. Such errors can be minimized by mentally “freezing” the microscopic image before making the motility estimate. One helpful technique is to determine whether more or less than 50% of the spermatozoa are motile. After making that determination, the observer can try to arrive at the nearest 25% and then the nearest 10%. The observer also should record the number of round cells present in each image. If more than two round cells are seen in each medium-power field, a smear of the semen should be made for cytologic evaluation (e.g., with Wright’s stain). The presence of white blood cells indicates inflammation or infection. The presence of early nucleated round germ cells indicates an aberration of spermatogenesis. Rams should have more than 30% progressively motile cells for a “satisfactory” rating and more than 70% for an “exceptional” rating 2,11,12 (Table 8-2). Motility usually is depressed outside the breeding season.

Sperm Morphology

A slide is next prepared for examination of spermatozoa morphology. A small drop of semen is placed on the edge of a slide, and a ribbon of eosin-nigrosin stain is placed slightly closer to the center of the slide. The corner of a second slide is dipped into the semen drop, and the resultant “hanging drop” of semen is mixed with the ribbon of stain. The second slide is then pulled across the first slide in a manner similar to that for creating a blood smear. The amount of semen placed on the edge of the second slide is determined by experience. The resultant smear should have an even distribution of cells. Spermatozoa should be spaced so that individual cells are easily distinguished but each field has approximately 10 cells. The slide is allowed to dry and then examined at 1000× with an oil-immersion lens. The observer should count at least 100 cells and determine a percentage of normal spermatozoa.

Abnormalities usually are recorded as either primary or secondary. Primary abnormalities involve the head and midpiece of the spermatozoa, whereas secondary abnormalities involve the tail (Figure 8-4). The type of abnormality can be used to estimate the severity of problems in rams with an excessive number of abnormal cells. Abnormalities of the head and the acrosome are associated with severe testicular aberrations. Tail abnormalities often are associated with less severe problems or diseases of the epididymis. Round droplets of cytoplasm on the tail usually are seen in young rams and are associated with overuse, immaturity, or mild testicular degeneration. Droplets also can occur in samples taken from rams out of season. At least 50% to 70% of the observed spermatozoa should be morphologically normal for the ram to be considered a satisfactory breeder; more than 80% to 90% normal is considered exceptional11 (Table 8-2).

Breeding Soundness Prediction

The SC, progressive motility, and percentage of normal spermatozoa can be combined to classify rams into categories to help predict their usefulness in a breeding flock. Rams that are classified as satisfactory in all categories can be expected to impregnate approximately 50 ewes in a 60-day breeding season. Rams that receive exceptional ratings can be expected to impregnate 100 ewes during a 60-day breeding season. Any ram that does not receive at least a satisfactory rating in all categories should either be culled or retested in 60 days. The decision to cull or retest should be based on the severity of observed lesions and the economic value of the individual animal.2,10–13

Ancillary Tests

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography can be used to evaluate the testicles of rams (or bucks). Changes from the normal homogeneous testicular parenchyma such as hyperechoic and hypoechoic areas are indicative of fibrotic changes or cystic structures. The examiner should not confuse the normal hyperechoic mediastinum that is found in the center of the testicle for a fibrotic lesion. The mediastinum appears as a distinct round area in the center of transverse images of the testicle and as a hyperechoic line on longitudinal images (Figure 8-5). The epididymis and spermatic cord also can be examined for fibrosis and cystic structures. Areas of fibrosis or degeneration and testicular abscesses usually can be visualized. 2

Testicular Biopsy

Testicular biopsy performed using a 14-gauge biopsy needle will retrieve tissue for direct examination of the testicular architecture. Testicular biopsy plus examination is useful in determining atrophy, degeneration, and hypoplasia. This technique usually is relegated to use in valuable animals. The clinician aseptically prepares the testicle and anesthetizes an area of skin. The biopsy needle is then inserted into the dorsum of the testicle while avoiding the epididymis, with care taken not to penetrate the mediastinum. Tissue can be fixed in either Bouin’s solution or 10% formalin for routine histopathologic analysis.14

Serologic Screening

Serologic screening in the form of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for Brucella ovis should be performed annually in all rams at the time of the BSE.2,13 Brucella ovis is a major cause of decreased infertility in flocks with multiple rams. B. ovis infection can have a significant impact on the production level of the flock by decreasing the number of multiple births, decreasing conception rates, and increasing the lambing interval. Ram epididymitis due to B. ovis is a contagious venereal disease that generally affects mature rams. The bacterium is transmitted through homosexual activities or by ewes during the breeding season. Ewes exposed to infected rams do not become permanently infected but serve as mechanical vectors for the spread of the disease. Thus all rams that test positive for B. ovis should be culled immediately.11

Breeding Soundness Examination in the Buck

All breeding bucks need to be evaluated for breeding soundness 3 to 4 weeks before onset of the mating season. As in the ram, the examination of the buck should include a physical examination, reproductive examination, measurement of SC, and semen collection and evaluation. BSEs are able to evaluate only the physical soundness and semen quality of the buck. A satisfactory rating cannot guarantee the buck’s ability to produce live offspring.2,15 Attempts to assess libido in the buck greatly aid in a complete reproductive evaluation. The libido measurement described for the ram can be adapted for the buck. 2

Physical Examination

Physical examination of the buck must include a general examination for health, with particular attention to assessment of body condition and musculoskeletal condition (feet and legs). To be a satisfactory breeder, a buck should be in good body condition. Use of thin or excessively fat animals should be avoided for breeding (see Chapter 2).15,16 The buck should be free of known genetic defects such as hernias, jaw malformation, cryptorchidism, supernumerary teats, and intersex condition. Bucks should not be phenotypically polled.

Examination of Reproductive Tract

Examinaton of the reproductive tract includes evaluation of the testes, epididymis, spermatic cord, and penis. Testes should be examined for size, symmetry, and consistency. A buck should have two large, oval testes of equal size; they are firm during the breeding season and slightly softer during the nonbreeding season. If only one testicle is present, the male should be disqualified as a potential breeder. Ultrasonography may be useful in aiding detection or confirmation of abnormalities.14–16 Gross changes in the epididymis are fairly rare in goats. The clinician should examine the penis for abnormalities when collecting a semen sample. The penis must be manually extended from the sheath so that a careful examination can be made. The urethra extends beyond the tip of the penis for approximately 2 to 3 cm, forming the urethral process. When bucks have a history of urinary calculi, the urethral process usually is removed during treatment because it is a common area of obstruction. The loss or removal of the urethral process appears to have no detrimental effect on the buck’s fertility.16

Scrotal Circumference

Because of its high correlation with testicular size and capacity for sperm production, SC is important in the buck. Its use in the evaluation of breeding soundness, however, is not well defined. SC is measured in the buck as described for BSE in the ram. SC in 45-kg dairy goats has been reported to be 25 to 28 cm, with larger bucks having SCs of 34 to 36 cm.15,16 No age and breed standards exist for SC in meat goats. In 1999, as measured with the Georgia and Southeast Meat Goat Buck Performance Test, SCs in 45-kg, 7-month-old Kiko and Boer bucks averaged 26 to 29 cm.17

Semen Collection

Semen may be collected with an artificial vagina (AV) in a trained buck or by means of electroejaculation.14 Electroejaculators should be 25 to 30 cm long and 2 to 3 cm in diameter. Many ram probes can be adapted for buck use. An AV can be built from a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipe or radiator hose with an inner liner made of a cut section of bicycle inner tube. An AV also can be purchased. The length of the AV should be 18 to 22 cm, and its outside diameter should be 6 cm. It should be filled with warm water to maintain proper turgor and warmth (38° to 40° C). A semen collection cone should be placed at one end. A nonspermicidal lubricant is placed in the open end.

For the electroejaculation procedure, bucks are restrained in chutes or held against the wall. The rectum is cleaned of feces and a well-lubricated probe is inserted. The prostate is massaged five to six times, electrical current is applied through the probe for 4 to 6 seconds, and then the probe turned off for 3 to 4 seconds. This pattern is maintained until ejaculation occurs (usually four to five cycles). Libido cannot be assessed when semen is collected using an electroejaculator. During and after collection, semen should be protected from direct sunlight and temperature shock, and sperm motility should be evaluated within 10 minutes.2

Semen Evaluation

The volume of normal buck ejaculate is 0.5 to 1.5 mL (with an average of 1 mL). Semen is evaluated for color and for sperm characteristics of gross and progressive motility, morphology, and concentration.16 Both semen quality and semen quantity may vary with age, season, temperature, and breed and even between individual animals within the same breed. Normal values for semen evaluation in the buck are as follows27:

Volume of semen: 1 mL (with a range of 0.5 to 1.5 mL)

Sperm motility: 80% (with a range of 70% to 90%)

Sperm concentration: 4 billion (with a range of 2 to 5 billion)/mL

Normal sperm morphology: 80% (with a range of 70% to 90%)

BOX 8-1 Minimum Acceptable Reproductive Criteria for a Satisfactory Potential Breeder Buck

Modified from Memon MA, Mickelsen WD, Goyal HO: In Youngquist RS, editor: Current therapy in large animal theriogenology, Philadelphia, 1997, WB Saunders.

Volume is measured directly from the graduated collection vial. Volume is of some value in evaluating semen collected using an AV, but of limited value when electroejaculators are used. The color of semen depends on the number of spermatozoa per milliliter; it can range from whey-like to milky to creamy. Gross motility is measured as described for the ram. Even though concentration is not routinely assessed in field conditions, it is advisable to include this measurement in the evaluation. Concentration can be easily assessed using a hemocytometer and a commercial Unopette system for white blood cell count.16 Morphology can be determined by examination. An eosin-nigrosin–stained smear is evaluated using a 1000× objective; the examiner measures primary or secondary abnormalities in 100 to 200 spermatozoa per slide, as described for the ram (see Figure 8-4). Normal values for a buck to be classified as a satisfactory potential breeder are listed in Box 8-1. A questionable potential breeder may require reevaluation after 8 weeks or need to be culled. The classification of unsatisfactory as a potential breeder may be assigned for reasons other than semen quality (e.g., cryptorchid, lameness). Bucks showing depressed libido, slightly decreased SC, and increased sperm abnormalities should be identified and culled.14,15

Selection and Management of Males

Ram

A ram with good-quality semen, adequate testicular size, and good libido can breed 100 ewes in a 17-day breeding season.2,7,11 Most producers in North America, however, use 3 to 3.5 rams per 100 ewes. Yearlings and mature rams can be expected to service 35 to 50 ewes, whereas ram lambs should be expected to service only 15 to 25 ewes.2 Adjustments should be made for multiple sire breeding units. It is desirable to always have more than three rams to a multiple sire unit, because this tends to alleviate some of the territorial fighting among rams.2

Libido and serving capacity testing can provide useful information regarding how many ewes a ram can be expected to service or even if a ram should be retained.7–9 Serving capacity tests are performed to measure how many times a ram services ewes during a defined period. One report suggests that the test serving pen should be approximately 3 m by 5 m and in clear view of rams that are to be tested.7–9 Larger or smaller pens may be used, however.

Serving capacity tests also may be used to determine proper ram-to-ewe stocking ratios. These tests of flock reproduction can produce a shorter, more uniform lambing season.7–9 Adult rams achieving four to six or more breedings during 30 minutes are preferred. Rams achieving two or three breedings during 30 minutes are acceptable. Rams that appear to be sexually inactive can be tested twice. If they still appear to be sexually inactive, the keeper can paint the rumps of the test ewes with different colors of ink and leave the tested ram overnight in the pen with them. The next day the keeper should examine the ram’s chest for the colored ink.2 Still, fertility is maximized if only acceptable groups of rams are kept for breeding.

Selection of rams from high-producing ewes as measured by the number of lambs born, the weight of lambs weaned, and a history of having lambs early in the season also may have a positive relationship with fertility.2 It appears that rams born co-twin to male siblings have higher serving capacities than those born co-twin to females.2,10 Rams also should be selected for structural soundness and for the genetic traits they can pass on to their offspring, because they contribute approximately 60% to 80% of the genetics of the average flock.3

Rams should be maintained on a good nutritional, vaccination, and deworming program. Their body condition scores before breeding season should be 3.5 to 4 (See Chapter 2, Figure 2-1). Obesity minimizes willingness to breed. Rams should be sheared and their hooves trimmed before breeding season. During breeding season, free access to shelter or shady areas should be provided to minimize heat stress–associated infertility. Special care should be taken during the initial examination of rams to eliminate those that have diseases of the reproductive tract. 2

Buck

Bucks are chosen on the basis of on individual performance or progeny testing for traits such as milk production, meat traits, adaptability, and twinning rate. Prolific bucks are preferred. Birth, weaning, and yearling information is valuable in establishing the superiority or inferiority of a potential sire. Selection for growth rate and meat production should be a high priority for meat goat producers. Bucks should have good conformation and be large and muscular. Selection based on testicle size is important; bucks with the largest testicles usually produce the highest-quality sperm.2

The same serving capacity tests used for rams are applicable to bucks. Bucks with apparent defects in posture and genital tract abnormalities should be avoided. Because the intersex condition has been linked to the polled gene, the use of phenotypically polled bucks should be avoided. Changing bucks every 2 years prevents loss of vigor and reduces inbreeding in the herd. Bucks should be kept separate from does in a group on pasture or in single housing. They should be introduced with females only during the established mating season, after which their job for the year is finished. Bucks require proper nutrition, routine foot care, vaccination, deworming, and exercise (see Chapter 19).

1. Burfening P.J., Rossi D. Serving capacity and scrotal circumference of ram lambs as affected by selection for reproductive rate. Small Rumin Res. 1992;9:61.

2. Goyal H.O., Memon M.A. Clinical reproductive anatomy and physiology of the buck. In: Youngquist R.S., Threllfall W.R., editors. Current therapy in large animal theriogenology. ed 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2007:511-514.

3. Fitzgerald J.A., Perkins A., Hemenway K. Relationship of sex and number of siblings in utero with sexual behavior of mature rams. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1993;38:283.

4. Grotelueschen DM, Doster AR: Reproductive problems in rams, NebGuide (online resource): http://www.ianr.unl.edu (Lincoln, Neb, 2000, University of Nebraska Cooperative Extension). Accessed January 12, 2010.

5. Fitzgerald J., Morgan M. Reproductive physiology of the ram. In: Youngquist R.S., Threllfall W.R., editors. Current therapy in large animal theriogenology. ed 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2007:617-619.

6. Katz L.S. Sexual performance tests in sexually inexperienced rams. In: Dziuk P.J., Wheeler M., editors. Handbook of methods for study of reproductive physiology in domestic animals. Urbana, Ill: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

7. Fitzgerald J., Perkins A. Serving capacity tests for rams. In: Dziuk P.J., Wheeler M., editors. Handbook of methods for study of reproductive physiology in domestic animals. Urbana, Ill: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

8. Perkins A., Fitzgerald J.A., Price E.O. Sexual performance of rams in serving capacity tests predicts success in pen breeding. J Anim Sci. 1992;70:2722.

9. Fitzgerald J.A., Perkins A. Ram sexual performance: a relationship with dam productivity. Sheep Res J. 1991;7:7.

10. Yarney T.A., Sanford L.M. Pubertal development of ram lambs: physical and endocrinological traits in combination as indices of postpubertal reproductive function. Therio. 1993;40:735.

11. Kimberling C.V., Parsons G.A. Breeding soundness evaluation and surgical sterilization of the ram. In: Youngquist R.S., Threllfall W.R., editors. Current therapy in large animal theriogenology. ed 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2007:620-628.

12. Bulgin MS: Ram breeding soundness examination and SFT form, Nashville, Proceedings of the Society for Theriogenology, Nashville, Tenn, 1992.

13. Pugh DG: Examination of the ram for breeding soundness, Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Hudson-Walker/Vaughn Theriogenology Conference, Auburn, Ala, 1996, Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine, p 19.

14. Carson R.L., et al. Examination and special procedures of the scrotum and testes. In: Wolfe D., Moll H.D., editors. Large animal urogenital surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1997.

15. Pugh D.G. Breeding soundness examination in male goats. Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Hudson-Walker/Vaughn Theriogenology Conference,. Auburn, Ala: Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine, 1996. p 29

16. Memon M.A., Mickelsen W.D., Goyal H.O. Examination of the reproductive tract and evaluation of potential breeding soundness in the buck. In: Youngquist R.S., Threllfall W.R., editors. Current therapy in large animal theriogenology. ed 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2007:515-518.

17. Mobini S. Reproductive management in goats. Orlando: Fla, 2000;vol 14,. Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference,

Diseases of the Male: Testicular Abnormalities

Varicoceles

A varicocele is defined as a localized dilatation and thrombosis of the internal spermatic vein and is recognized as a fluctuant to hard swelling in the spermatic cord. Varicoceles are more common in rams than in bucks. This condition often is manifested as rear limb lameness and awkward posture as the ram tries to relieve pressure on the swollen cords. Affected animals may become weak and susceptible to other diseases as a result of debilitation brought on by an unwillingness to walk to obtain food and water. Varicoceles can be diagnosed by palpation and diagnostic ultrasound imaging. Abnormalities such as decreased total sperm count, reduced sperm motility, and morphologic abnormalities of the sperm often are associated with varicoceles. The exact etiology of the condition is not known, but a genetic predisposition is suspected. No easy treatment is available, and affected rams or bucks should be culled.1

Epididymitis in Older Males

Epididymitis is a rare condition in the buck but a clinically important disease in rams. Epididymitis in rams should be considered to be caused by B. ovis until proved otherwise. This is true especially in older rams that have been actively breeding in multiple sire units. However, one case report involving an outbreak of B. ovis in a group of virgin ram lambs suggests that the disease may be spread in utero or neonatally, before any known sexual activity.2 The primary means of spread is thought to be contact with mucous membranes, which results in bacteremia. The organism localizes in the epididymis and secondary sex glands. Contact can occur among rams and with recently infected ewes; venereal and oral-nasal modes of transmission also are possible.3

Swelling of the epididymis is the primary presenting sign, appearing approximately 3 weeks after the initial exposure. On gross examination, localized inflammation is present, followed by hyperplasia and obstruction of the epididymal ducts. This obstruction causes a backup of spermatozoa, the development of sperm granulomas, and pressure necrosis. The seminal vesicles also are commonly affected, which may account for the large number of infected rams that show no palpable signs of epididymitis.3 Semen collected from infected rams usually contains a large number of polymorphonuclear neutrophils, which can be seen on the motility preparations or on Wright’s-stained specimens. Microscopic evaluation of Stamp’s modified Ziehl-Neelsen–stained semen also can be a useful tool in diagnosis. The coccobacillus Brucella will stain red against a blue background. Culture for the presence of Brucella organisms is a good diagnostic tool in suspected cases.

Serologic testing for B. ovis should be considered a routine part of a BSE. An ELISA and a complement fixation test are currently available. An experimental PCR assay appears to give results similar to those with semen culture and may soon be available.3,4 Herd infections with B. ovis can result in a 15% to 30% reduction in lambing rate, depending on the chronicity of the herd problem. This decrease in reproductive efficiency results from lowered fertility in the rams, failure of the ewes to conceive, reabsorption of embryos, abortions, stillbirths, and birth of weak lambs.5,6

Recommendations outlined by Bulgin6 include the following:

• Buying virgin rams that have been serologically tested for brucellosis

• Keeping newly purchased rams separate until all rams are tested free from Brucella

• Performing palpation for epididymitis and culling all affected rams before the breeding season

• Culling all B. ovis–positive rams

• Retesting all rams in the flock 60 days after any rams are found to be seropositive

• Performing BSEs yearly on all rams

If a large number of serologically positive rams are found after a year of adherence to these guidelines, efforts should be made to determine whether a serologically negative carrier ram is present in the flock by culturing semen from all rams.

Epididymitis in Young Males

In younger rams and, less commonly, in bucks, epididymitis can be caused by a number of organisms such as Histophilus, Actinobacillus, and Haemophilus spp., as well as Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis and possibly other pathogens.7,8,9 Lamb epididymitis can be spread from ram to ram by the oral or nasal route. The organisms responsible for lamb epididymitis frequently can be cultured from the preputial cavity of rams younger than 2 years of age and commonly are found in the mucous membranes of the prepuce, penis, mouth, and nasal cavity.5 Colonization and subsequent disease of the reproductive tract may depend on the hormonal changes that occur during maturation and puberty, along with other unknown differentiating factors that allow most animals to eliminate the bacterium spontaneously while causing others to develop clinical signs.10 Experimentally, suppurative epididymitis and spermatic granulomas may be seen within 24 and 72 hours, respectively, after inoculation with some pathogens.11

Lamb epididymitis can be treated with injections of long-acting oxytetracycline (20 mg/kg intramuscularly [IM] or subcutaneously [SC]) for three treatments at 3-day intervals.10,12 Inclusion of tetracycline (20 mg/kg by mouth [PO] daily) products in the ration may be appropriate in herds experiencing a high incidence of lamb epididymitis. Treatment should be reserved for valuable lambs and cases diagnosed in the early stages, because, in most affected lambs, subsequent development of scar tissue in the epididymis prevents functional recovery.

Orchitis

Orchitis is a common condition in the ram and is occasionally seen in the buck.13–15 Scrotal abscesses may be caused by trauma or may be an extension of epididymitis. Whenever testicular trauma or infection is encountered, it should be considered a medical emergency in breeding animals. Excessive heat from one testicle can result in potentially irreversible thermal injury to the germinal epithelium of the contralateral testicle.7 All of the organisms discussed in the section on epididymitis can cause orchitis. Clinical findings include a hot, swollen scrotum (usually unilateral); inability to move the affected testicle freely in the scrotum; and pain on manipulation of the affected testicle and the scrotum. Some animals may show signs of systemic disease, pain on walking, and decrease in libido.15 In cases affecting valuable animals, hemicastration in the acute phase may prevent permanent infertility.

Sperm Granulomas

Although testicular tumors are rare in rams and bucks, granulomatous swellings are occasionally encountered. Sperm granulomas are more common in goats than in sheep, and unlike abscesses or other lesions of orchitis, they are bilateral. Formation of sperm granulomas often is caused by a partial or complete blockage of the efferent ducts draining into the epididymis.15 As pressure builds, the ducts become distended and may rupture, resulting in a severe inflammation. With accumulation of fluid, pressure continues to build, and testicular degeneration may occur. Some animals initially are fertile but lose fertility after the efferent ducts become completely occluded.

Testicular Hypoplasia and Degeneration

Testicular hypoplasia and degeneration are difficult to differentiate during an initial examination.13,15 In rams and bucks out of season, changes in testicular size and palpation characteristics may be difficult to differentiate from subtle testicular atrophy. More extreme differences are encountered in rams than in goats, but in general, the testicle in the nonbreeding season is smaller and lacks the usual resilient consistency.13 True hypoplasia can be associated with the intersex condition in bucks and with a specific chromosomal abnormality in rams.13,15

Other causes of testicular atrophy include zinc deficiency, hypothyroidism (iodine deficiency, ingestion of goitrogenous plants), starvation diets, systemic disease, and heat and cold stress. Iodine-induced hypothyroidism has been associated with decreased testicular weight, depressed spermatogenesis, and decreased libido. Atrophic or degenerated testicles become elongated, smaller, and either softer or harder. Normal testicles usually exhibit a homogeneous echogenicity on ultrasound imaging. Atrophic or degenerative testicles tend to have a heterogeneous pattern and more pronounced hyperechoic areas than do normal testicles.16 Testicular biopsy can be of value in diagnosis.

In many cases, testicular atrophy and degeneration are not treatable; the exceptions are cases caused by diet or certain diseases. In treating diet-related atrophy, ensuring adequate protein-energy intake and free access to a good-quality trace mineral supplement is essential. If zinc deficiency is suspected, reducing the legume content of the diet and adding a chelated form of zinc (zinc methionine) to the diet or trace mineral mixture will be of benefit. If iodine-induced hypothyroidism is diagnosed, the inclusion of iodine in a trace mineral mixture and the removal of goitrogenous plants from the diet are recommended; males should be kept off pastures with goitrogenous plants before and during breeding.7

Cryptorchidism

Cryptorchidism occurs when either one or both testes fail to descend from the abdominal cavity into the scrotum. The retained testicle may be located at any point along the normal path of descent. Among unilateral cryptorchids, the right testicle is retained in the abdomen in approximately 80% to 90% of affected animals.17,18 A higher incidence also has been reported in intersex animals. However, cryptorchidism is not related to the intersex condition in Angora goats. In Angora bucks, cryptorchidism is a recessive trait.19 The diagnosis is made by physical examination. Cryptorchidism is rare in ruminants, and cases often are complicated by a previous hemicastration. If either the history or physical findings suggest the presence of a testicle within the abdominal cavity, then an exploratory laparotomy should be performed to remove the retained testicle. Because this condition is thought to be heritable, cryptorchid bucks should not be used for breeding, and their sires and dams also should be culled.20

Intersex

Caprine intersex animals are referred to as male pseudohermaphrodites because a majority of them have testes. True hermaphrodites have testicular and ovarian structures and generally constitute a much smaller proportion of intersexes.21 Intersex is more prevalent among polled dairy goats (Saanen, Toggenburg, Alpine, and Damascus breeds). The polled intersex condition is rare or not reported in some breeds (e.g., Nubian and Angora).22 Cytogenetic evaluations of caprine intersexes clearly show that most polled intersexes are karyotypically female (XX), and the breeding histories of the parents indicate that intersex animals are homozygous for the polled trait.15

Affected animals are genetically female but may exhibit male, female, or mixed external characteristics.22 Generally, they are female-appearing at birth, but as they reach sexual maturity, they become larger than normal females, with masculine-appearing heads and erect hair on the neck.10 An enlarged clitoris in a doe-like animal or a decreased anogenital distance in a more masculine-appearing animal is typical of intersex22 (Figure 8-6). Intersex animals may start to smell and may act aggressively toward other goats and people during the breeding season. Some dribble urine or stretch out with a concave back and urinate forward between the legs.21 Whenever bilateral cryptorchidism is encountered, intersex should be suspected. The testes generally are intraabdominal (in the normal location of the ovaries), but they may be partially or totally descended.7 Partially descended testes may be mistaken for udders, especially when they begin to enlarge during puberty.21 Hypospadias (opening of the urethral orifice on the ventral aspect of the penis), formation of sperm granulomas, and hypoplasia of testicles all should be considered part of the intersex complex.15,23

The principal hormone produced by the gonads in caprine intersexes is testosterone, which accounts for the masculine behavior. Intersex goats can be used as teaser animals because they do not produce sperm.7 Gonadectomy generally is required if the animal is to be used as a pet. Identifying intersex animals with normal or nearly normal external genitalia is difficult. Failure to exhibit estrus, development of male behavior during the breeding season, a shortened vagina on speculum examination, and smaller-than-normal teats may be the first signs of the intersex condition.22 The breeding of phenotypically polled bucks should be avoided.

Diseases of the Male: Penile Abnormalities

Hypospadias

Several penile abnormalities may occur, albeit rarely, in sheep and goats.7,23–25Both hypospadias and short penile length are associated with intersex in goats. Such animals should be culled. Careful examination of the penis in the fully extended state may reveal existing abnormalities. Occasionally urethral rupture (occurring as a complication of urethral stones), balanoposthitis (see Chapter 12), injuries to the vermiform appendage, hair rings, and other abnormalities are identified.7

Ulcerative Posthitis

Ulcerative posthitis (enzootic posthitis, sheath rot, or pizzle rot) is an infectious, inflammatory condition of the penis, prepuce, and sheath of sheep and goats consuming high-protein diets.7,26 The disease is caused by an interaction of the local bacterial flora (e.g., C. renale) with excess urinary urea. Excess ammonia may damage the mucosal surfaces, resulting in swelling of the prepuce, necrosis and ulceration of the preputial mucosa, and straining to urinate. Removing the animals from the high-protein diet and shearing the “prescrotal” wool or hair usually will relieve the condition. Antibiotics, disinfectants, and antiinflamatory drugs may be needed in some cases (see Chapter 12).

Phimosis

Both phimosis (inability to extend the penis) and paraphimosis (inability to withdraw the penis into the prepuce) occasionally are seen in rams and bucks; both conditions can cause significant loss of libido and fertility. If they are not quickly diagnosed and treated, affected animals may be rendered infertile. These two conditions may be associated with hair ring, trauma, and balanoposthitis. In cases associated with a hair ring on the glans of the penis, inspecting the penis allows the clinician to identify the problem and remove the “ring” of hair.7 Shearing the wool or mohair just anterior to the sheath can minimize the incidence of this problem.13,15 Phimosis also may occur as a sequela to trauma, balanoposthitis, and congenital abnormalities. With traumatic injury, an adhesion may form in the sheath or in the sigmoid region, resulting in an inability to extend the penis. As a general rule, these cases may be difficult to treat. When inflammation and scarring result in posthitis, the treatment is the same as that described for balanoposthitis. The clinician can attempt to “break down” the adhesions manually. The use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (e.g., flunixin meglumine 1 to 2 mg/kg twice a day) or antibiotics (e.g., procaine penicillin 22,000 IU/kg twice daily) and lavage of the sheath with mild antiseptics may be of benefit. With phimosis, most animals experience a loss of libido and should be culled, because the prognosis is poor.15

Paraphimosis

Paraphimosis also is associated with trauma, infection, and balanoposthitis. It is slightly more common in bucks than in rams, but it is rare in both. In cases of paraphimosis, applying antibiotic cream with or without corticosteroids, replacing the penis, and placing a pursestring suture into the preputial orifice may be of value. Placement of a tube in the sheath, exiting through the orifice, allows urine drainage. The clinician should take care to ensure proper urine flow. Flushing the sheath and penis with a mild antiseptic solution, providing penile hydrotherapy, and covering the penis with medicated ointments are valuable treatments for this condition. The penis should be manually extended at least every third day so that the keeper or the clinician can monitor healing. Sexual rest should be enforced throughout recovery. The prognosis in these cases is poor, however, particularly if the condition is of greater than 2 weeks’ duration and the animal makes no attempt to retract the penis.15

1. Kimberling C.V. Disease of rams. In Kimberling C.V., editor: Diseases of sheep, ed 3, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1988.

2. Bulgin M.S. Brucella ovis epizootic in virgin ram lambs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1990;196:1120.

3. Saunders V.F., et al. Multiplex PCR for the detection of Brucella ovis, Actinobacillus seminis and Histophilus somni in ram semen. Aust Vet J. 2007;85:72-77.

4. Manterola L., Tejero-Garces A., et al. Evaluation of a PCR test for the diagnosis of Brucella ovis infection in semen samples for rams. Vet Microbiol. 2003;92:65-72.

5. Kimberling C.V. Sheep flock fertility, Proceedings of the Annual meeting of the Society for Theriogenology. Nashville: Tenn; 1990.

6. Bulgin MS: Epididymitis caused by B. ovis, Proceedings of the Annual meeting of the Society for Theriogenology, Nashville, Tenn, 1991.

7. Mobini S., Heath A.A., Pugh D.G. Theriogenology of sheep and goats. In: Pugh D.G., editor. Sheep and goat medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:129-196.

8. Ferreras M.C., et al. Unilateral orchitis and epididymitis caused by Salmonella enterica subspecies diarizonae infection in a ram. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2007;19:194-197.

9. Walker R.L., Leamaster B.R. Prevalence of Histophilus ovis and Actinobacillus seminis in the genital tract of sheep. Am J Vet Res 47. 1928:1986.

10. Bulgin MS: Ram lamb epididymitis, Proceedings of the Annual meeting of the Society for Theriogenology, Nashville, Tenn, 1991.

11. Al-Katib W.A., Dennis S.M. Early sequential findings in the genitalia of rams experimentally infected with Actinobacillus seminis. N Z Vet J. 2008;56:50-54.

12. Ley W.B. Ram epididymitis. Agri-Pract. 1993;14:34.

13. Bruer A.N. Examination of the ram for breeding soundness. In Morrow D.A., editor: Current therapy in theriogenology, ed 2, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1986.

14. Pugh D.G. Breeding soundness evaluation in male goats, Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Hudson-Walker/Vaughn Theriogenology Conference. Auburn, Ala: Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine; 1996. p 29

15. Mickelsen W.D., Memon M.A. Infertility and diseases of the reproductive organs of bucks. In Youngquist R.S., Threlfall W.R., editors: Current therapy in large animal theriogenology, ed 2, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2007.

16. Ahmad N., Noakes D.E., Middleton D.J. Use of ultrasound to diagnose testicular degeneration in a goat. Vet Rec. 1993;132:436-439.

17. Ott R.S., Memon M.A. Breeding soundness examination of rams and bucks, a review. Theriogenology. 1980;13:155.

18. Smith K.C., Brown P.J., et al. Cryptorchidism in North Ronaldsay sheep. Vet Rec. 2007;161:658-659.

19. Skinner J.D., Van Heuden J.A.H., Goris E.J. A note on cryptorchidism in Angora goats. S Afr J Anim Sci. 1961;20:10.

20. Riddell M.G. Developmental anomalies of the scrotum and testes. In: Wolfe D., Moll H.D., editors. Large animal urogenital surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1997.

21. Basrur P.K., Kochhar H.S. Inherited sex abnormalities in goats. In Youngquist R.S., Threlfall W.R., editors: Current therapy in large animal theriogenology, ed 2, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2007.

22. Smith M.C., Sherman D.M. Goat medicine. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1994.

23. King W.W., Young M.E., Fox M.E. Multiple congenital genitourinary anomalies in a polled goat. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2002;41:39-42.

24. Smith K.C., Brown P., Parkinson T.J. Hypospadias in rams. Vet Rec. 2006;158:789-795.

25. Fuller D.T., et al. What is your diagnosis? Hypospadias and urethral diverticulum. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992;201:1232-1431.

26. Loste A., et al. High prevalence of ulcerative posthitis in Rasa Aragonesa rams associated with a legume-rich diet. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 2005;52:176-179.

Special Surgical Procedures in the Male

Castration

Castration of the normal young male is among the most commonly performed surgical procedures in small ruminants. Kids and rams are castrated for management and production reasons. Mohair production was higher in castrated goats than in intact ones.1 Castration of kids fed to slaughter increased carcass weight, dressing percentage, and external fat score while reducing internal fat score.2 Volumes of publications are available detailing the effects of age at castration and techniques used on carcass quality and growth rates. This component of meat production management is beyond the scope of this discussion; here, the focus is on the procedures for different techniques of castration.3–5

Some producers delay castration in animals intended to be used as work or pet animals, which will have an extended life span in comparison with those used for meat. An emerging trend is to delay castration in some meat goats that are fed a very high-concentrate diet and used for show before slaughter. This practice often is related to concerns of urolithiasis. Although such findings often are debated, at least one study evaluating the effect of castration on penile length and diameter and urethral diameter determined that lambs castrated before 3 months of age did not have the same penile development as in intact lambs or ones castrated at 5 months of age.6 Most important, relative to urolithiasis, the urethral cross-sectional diameter also was significantly smaller in the lambs castrated before 3 months of age when compared with that in intact lambs. The lambs castrated at 5 months of age did not show a significant difference in penile or urethral diameter from the intact lambs.6

Most producers castrate their own animals, although veterinarians may be called on to perform routine castrations in small flocks or on older animals that were not castrated at an early age for whatever reason. The most frequently used techniques are the bloodless procedures using elastrator bands or the Burdizzo emasculatome. Alternatively, traditional surgical excision of the testes may be done. Each method has advantages and disadvantages, but the method chosen often becomes a matter of individual operator bias. The elastrator band technique frequently is used in lambs and kids younger than 1 week of age in conjunction with tail docking or dehorning. It can be used up to the age of 3 or 4 months, depending on the size of the animal, but is better done earlier. The animal may be restrained with rear end up by holding hind limbs or smaller animals may be held with front and rear limbs of each side held together. The elastrator band should be placed in a disinfectant before use. Special pliers are used to place the band around the proximal scrotum, with care taken to ensure that both testicles are distal to the band. With proper placement, the band will be distal to the rudimentary teats; an important step is to ensure that the penis has not been included within the band (Figure 8-7). The elastrator band restricts blood flow to all tissues distal to the band, with subsequent avascular necrosis and sloughing of the tissue of the scrotum and testes. Sloughing usually occurs in 7 to 10 days. The resulting open tissue is a prime area for infection with clostridial organisms. Tetanus is not an uncommon sequela to castration, especially when elastrator bands are used (Figure 8-8). Therefore any animal not previously vaccinated for clostridial diseases should be administered both tetanus antitoxin and tetanus toxoid at the time of castration. The tissue distal to the elastrator band may be excised 1 or 2 days after band application, to lessen the risk of complications. If one (or both) testicles are proximal to the band, the animal will exhibit characteristics of an intact male; nevertheless, it probably will be infertile because of improper thermoregulation of the testes displaced proximally near the external inguinal ring. In such instances, surgical castration will be required to remove the remaining testis. The procedure will be more difficult than a normal castration because of fibrous tissue and adhesions. If the penis has been included in the band, the point of capture usually is at the distal bend of the sigmoid flexure. Consequent urethral obstruction and rupture will necessitate euthanasia of the kid or ram, or at the very least an urethrostomy.

Although both the elastrator band and Burdizzo emasculatome techniques are so-called bloodless techniques, many practitioners still prefer surgical castration by excision of the distal one half to one third of the scrotum with a scalpel blade or using a Newberry knife to leave two flaps of scrotal skin (cranial and caudal). The testicles are exposed and removed after making the skin incision of choice (Figure 8-9). Many clinicians prefer to place ligatures on the spermatic cord or to crush the cord with an emasculator, to ensure appropriate hemorrhage control. Care should be taken in using an emasculator routinely used for larger species such as horses in that an emasculator that functions well in equine castration may not adequately crush the smaller cord of the small ruminant. Therefore the clinician may prefer to use ligatures; this method takes very little time and does not involve appreciable added expense. The spermatic cord is then transected distal to the ligature. The testicles may be removed by traction, as is commonly done in calves, but this method has been associated with herniation almost immediately after the castration in some cases. If the traction method is selected, pressure should be applied over the respective external inguinal ring with fingers while pulling the testes with the other hand to minimize trauma to the ring and subsequent herniation. Animals younger than 2 months of age may be castrated in this manner with use of physical restraint, but older animals should have local anesthesia and sedation, if not general anesthesia. An alternative to traditional castration equipment is the Henderson castration tool.7–9

Figure 8-9 In this photo, the ram lamb is being restrained by a sitting holder (as described in Chapter 1). The surgeon is removing the distal one half to one third of the scrotum to expose the two testicles. The testicles were then separated from the surrounding tissues and removed by “pulling,” and the goat was examined for inguinal hernia and given a tetanus toxoid inoculation. (Note: Routine spraying of insect repellant around the scrotal area after castration is recommended by D.G.P., regardless of the controversy surrounding this practice.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree