Some of the common goals of early limb use exercises are to improve active pain-free range of motion; muscle mass and muscle strength to allow weight bearing, balance, and performance of activities of daily living; lameness; aerobic capacity; and weight loss and to help prevent further injury.1–4 The focus on patients that have serious afflictions with limited to no weight bearing on the affected limbs centers on early limb use and is the topic of this chapter. As patients are able to bear weight and begin to use their limbs, the emphasis shifts to improving proprioception and balance for patients with neurologic conditions or those recovering from joint injury or surgery, as described in Chapter 28. Finally, as patients improve with an approach to maximal expected function, the emphasis should be on strength, speed, and joint motion exercises, which are the focus of Chapter 30. Treatment considerations and the choice of exercises vary with each stage of tissue repair and endurance. As the animal improves clinically and tissue healing progresses, the exercise plan should be altered to match the animal’s progress and appropriately challenge the involved tissues. The intensity of an exercise may be increased or reduced by changing the duration of time that an animal performs an exercise, the frequency with which an exercise is performed, and the rate or speed at which a particular exercise is performed (Box 29-1). Any of these may be altered to fine-tune an exercise prescription to achieve the expected outcome goals. In general, the frequency of the activity is increased first if the patient is severely affected. For example, a realistic initial goal for a morbidly obese, deconditioned patient with degenerative joint disease may be to increase the amount of time the dog is able to comfortably tolerate walking by increasing the frequency of leash walks from twice daily to three times daily and finally to four times daily. This strategy helps to improve endurance and promote weight reduction, while limiting fatigue or muscle soreness. Increasing the length or duration of activity is usually the next phase of activity. For example, the dog may progress from walking 5 minutes four times per day to 6 minutes four times per day the next week. Increasing the speed at which the dog walks may not be a realistic initial goal for this animal at this point. A contrasting example may be an athletic animal recovering from injury that must be challenged to improve speed and endurance to meet the goal to return to performance activity. This type of patient may progress from jogging 20 minutes per session to playing ball in an enclosed run. It is important for the therapist to have an understanding of exercise intensity and what is appropriate for each patient during rehabilitation treatment. Routine reevaluation of the patient is recommended to assess the adaptations that are occurring with the rehabilitation treatment plan and to determine the appropriate rate of progression. Maximal assisted standing is appropriate for patients that are unable to support their body weight as a result of paralysis, paresis, pain, trauma, postoperative precautions, or general debilitation. Maximal assistance may be defined as support of 75% to 100% of the patient’s body weight by the handler to maintain a standing posture. Animals with multiple orthopedic injuries (especially pelvic fractures following repair or after a period of healing), neurologic conditions, or severe debilitation are excellent candidates for assisted standing exercises (Figure 29-1). Assisted standing exercises are among the first therapeutic exercises prescribed for severely afflicted animals that are unable to independently rise from a recumbent position or support their own body weight, and may begin in patients that are receiving adequate pain control following injuries that are stable. Animals with unstable injuries or in pain resist standing and may further injure themselves or the therapist while struggling. The animal should be encouraged to support its body weight as it is able, and the therapist gives only the necessary assistance to maintain the standing position (Figure 29-2, A). While supporting the animal, the handler slowly releases tension on the assistive device, allowing the animal to continue weight bearing as much as it is able. Alternatively, it may be easier for the therapist to support the patient manually with a hand placed on the ventral pelvis to maintain the rear limbs in a normal position, preventing inappropriate crossing or a base narrow stance. Because the animal is encouraged to accept and support a portion of its weight, strength, balance, coordination, and proprioception are challenged. If the dog begins to collapse, the sling is gently pulled up to assist the patient back into the standing position and the exercise is repeated (Figure 29-2, B). It is important to place the limbs in a square standing position to give neuromuscular feedback and to also allow the animal to stand in a stable fashion. The next progression in standing activities is standby assisted standing. At this point of the recovery, the animal has the strength and motor control necessary to support itself against gravity in a standing position. However, it may still experience ataxia or weakness and have an occasional loss of balance, requiring standby assistance. The therapist should be behind the animal or at the animal’s side, ready to guard against a fall caused by a loss of balance (Figure 29-3). The therapist does not assist the dog unless support is needed to prevent a fall. As strength improves, the patient will be more willing to advance the limbs if motor function is present. In cases of hindlimb paresis, the therapist may also challenge the patient further by lifting a forelimb to encourage weight bearing on the hindlimbs. It is also beneficial to lift a forelimb in dogs with unilateral hindlimb weakness to shift the weight to the hindlimbs. Standing in water may be a valuable activity for large patients with generalized weakness, lower motor neuron disease, or other conditions resulting in inability to stand and support weight. The buoyancy of the water often results in a patient’s willingness to try to stand and bear some weight; often these patients will not even try to stand on dry ground. Supportive devices, such as life vests, slings, or harnesses may be used to provide further assistance and support. The reader is referred to Chapter 31 on aquatic therapy for further details. Nonambulatory patients may benefit from placement in a body sling or harness to provide support for standing (Figure 29-4). It may be easier to use a lift device in conjunction with a sling to help support larger patients (Figure 29-5). An advantage of a sling is that the patient is able to maintain a body position with the limbs placed under the body in a standing position with partial or complete support of body weight, which provides an opportunity for limb strengthening and early proprioceptive training. Frequent episodes of supported standing also help to relieve pressure on bony prominences and may reduce the chances of decubital ulcer formation and pulmonary complications. Excessive congestion of the lungs that may result from spending long periods in lateral recumbency may be prevented with early implementation of standing in a sling. The body sling must be adjusted properly so that respiration is not compromised and the limbs are not compressed in the openings of the sling. Proper padding is also important for comfort. The skin should be inspected after each session in the sling to identify areas of potential skin irritation or breakdown. Rubber bungee cords may be used to secure the sling to the supporting frame. This may aid in the facilitation of weight bearing and movement during the sling sessions. The elasticity of the cord permits some gentle up-and-down movement that encourages the animal to safely bear partial weight on its limbs. It also may allow some attempts to move forward, backward, and side to side. A gentle bouncing motion may be manually introduced by the therapist to initiate rhythmic stabilization of muscle groups throughout the trunk and limbs.

Therapeutic Exercises

Early Limb Use Exercises

Standing Exercises

Assisted Standing Exercises

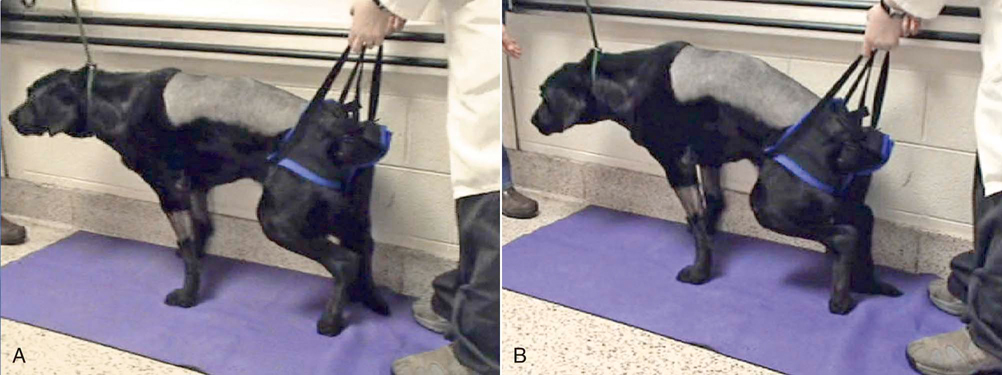

Figure 29-1 Support while standing is beneficial for patients with limited ability to stand and bear body weight. A sling may be used to provide support for maximal assisted standing of a patient.

Figure 29-2 Tetraparesis or other conditions causing weakness in multiple limbs. A, Use of a sling to help provide support for standing. B, As the patient begins to fatigue and attempts to sit, the therapist lifts the dog back into a standing position.

Standby Assisted Standing

Aquatic Standing

Aids for Assisted Standing

Body Slings

Figure 29-4 A sling that may be used to assist standing. Standing helps the patient develop stamina and endurance with minimal assistance required from a therapist.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Therapeutic Exercises: Early Limb Use Exercises

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue