Chapter 120The Western Performance Horse

The Cutting Horse

The Cutting Horse

Jerry B. Black and Robin M. Dabareiner

Diagnosis and Management of Specific Lameness

Selected Lameness of the Tarsus

Selected Lameness of the Stifle

The Roping Horse

The Roping Horse

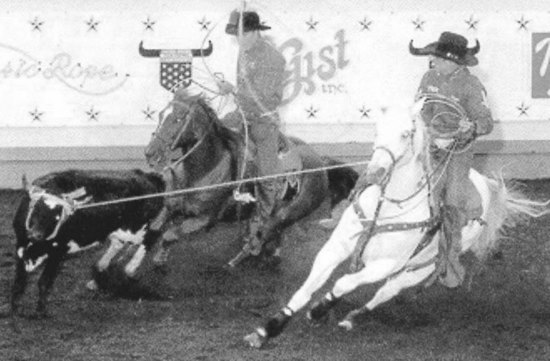

Team Roping Horse

Historical Data and Decreased Performance

It is imperative for a clinician to know whether a team roping horse is used primarily as a heading or heeling horse. In addition, a thorough description of the owner’s complaint of a change in or decreased performance provides valuable insight into the underlying problem, bearing in mind that often in the early stages little or no lameness may be present. Eighty-nine of 118 (75%) team roping horses had a history of lameness, and 29 (25%) had an owner complaint of decreased or altered performance.1 The type of performance change differed between horses used for heading or heeling (Figures 120-1 and 120-2).