9 The vomiting and/or diarrhoeic cancer patient

Vomiting is the active expulsion of material from within the stomach and/or upper small intestine. Vomiting should always be differentiated from regurgitation either by careful history evaluation or by direct observation. Vomiting usually causes a prodromal nausea (characterized by salivation, lip licking, appearing anxious or pacing) and then usually proceeds to retching, whilst a regurgitating patient does not usually exhibit these features. Vomiting also usually involves visible contraction of the abdominal muscles whereas regurgitation usually does not. Analysis of the vomitus itself usually reveals a pH less than 5 (regurgitated fluid should not be acidic) unless there is bile present, in which case the pH will often be alkaline. Assessment of the vomitus for the presence of bilirubin (either based on the yellow-green colour or by using a simple urine dipstick) can therefore sometimes be helpful too.

Vomiting can be caused by disease in many areas of the body and therefore from an oncological point of view, may indicate the presence of a tumour in locations other than the stomach. It is helpful to adopt a logical body-systems-based approach to the investigation of a vomiting cancer patient, by considering where and what type of tumour may be present as shown in Box 9.1.

Box 9.1 Types of tumour that could be associated with causing vomiting

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 9.1 – GASTRIC ADENOCARCINOMA IN A DOG

Case history

The relevant history in this particular case was:

Diagnostic evaluation

Theory refresher

Initial diagnostic evaluation, as in the clinical case example, can frequently appear unremarkable. Positive contrast radiographic studies may reveal a lesion within the gastric lumen, or be suggestive of gastric ulceration, but ultrasound may often not reveal the presence of a lesion unless it is located within the distal third of the stomach due to the difficulties of imaging the cranial areas of the stomach, unless it is fluid-filled. However, ultrasound can be very useful to assess the gastric and mesenteric lymph nodes and if these are found to be enlarged, to enable ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration to be performed. Many gastric tumours are diagnosed late in the clinical stage of the disease, by which time, metastasis to the local lymph nodes or other surrounding organs may have occurred, so such assessment is essential in the clinical staging of the disease. Ultrasound can also reveal the loss of layering of the gastric structure that may be seen with an infiltrative condition such as lymphoma.

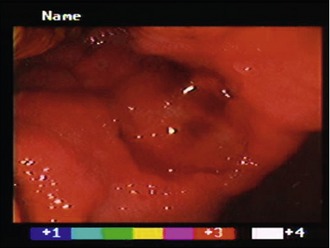

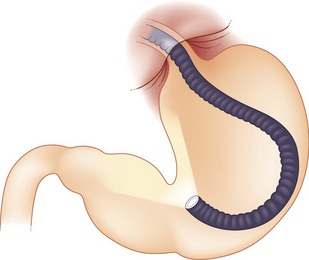

Flexible endoscopy is very useful to identify intraluminal lesions but it is vital that a logical, stepwise examination technique is adopted to ensure that all the gastric mucosa has been thoroughly visualized. Although the majority of gastric tumours in the dog will be located on the lesser curvature or within the antrum, it is important to remember that a ‘J-manoeuvre’ must be performed to ensure that the cardiac area has been fully examined, as it is possible for small tumours to exist just behind and above the gastro-oesophageal junction and these are easy to miss on simple aboral evaluation if the endoscope is not retroflexed (Fig. 9.2).

Figure 9.2 The ‘J-manoeuvre’;

adapted from ‘Veterinary Endoscopy for the Small Animal Practitioner’, Timothy C McCartney, Elsevier-Saunders 2005, p. 294

Other benign or lower-grade malignant gastric tumours may be more amenable to surgical excision, thereby illustrating the importance of attempting to obtain a presurgical diagnosis if possible. Leiomyomas appear to be found more frequently in the proximal third of the stomach and can usually be removed via a midline laparotomy. Partial gastrectomy has been greatly facilitated in recent years by the use of surgical stapling equipment such as the TA-55 and TA-90 (p. 201). At the time of surgery it is important to examine and biopsy local lymph nodes and any suspicious areas on the surface of the liver or within the omentum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree