Chapter 47 The Systemic Mycoses

BLASTOMYCOSIS, COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS, CRYPTOCOCCOSIS, HISTOPLASMOSIS

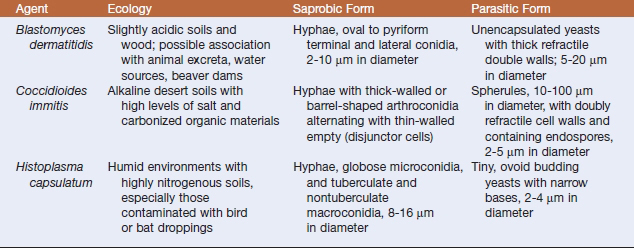

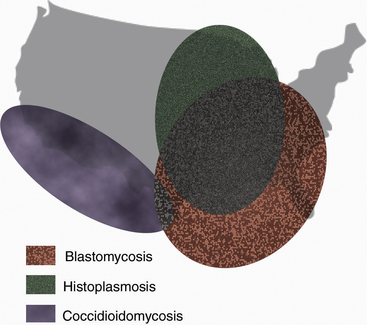

The systemic mycotic agents are inherently virulent and can cause disease in healthy individuals. The four veterinary pathogens in this group are Blastomyces dermatitidis, Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum, Coccidioides spp., and Cryptococcus neoformans, which exhibit unique biochemical and morphologic features that enable them to evade host defenses and cause disease. Three of these pathogens, B. dermatitidis, H. capsulatum, and Coccidioides, are thermally dimorphic, growing as molds at 25° C and as yeasts at 37°C (Table 47-1). Blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis tend to be restricted to certain geographic regions (Figure 47-1).

FIGURE 47-1 Geographic distribution of blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and histoplasmosis.

(Courtesy Ashley E. Harmon.)

BLASTOMYCOSIS

Disease and Epidemiology

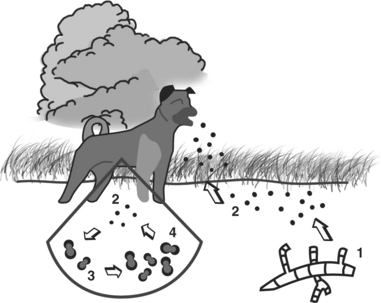

This thermally dimorphic fungus appears to be an inhabitant of soil and wood. Environments that are moist and shaded, have a high content of organic matter, and have slightly acidic pH seem to favor its growth. The ecologic niche of B. dermatitidis has been associated with water sources that change water levels. In highly endemic areas, shorelines may be an important reservoir for the fungus (Figure 47-2). Successful environmental isolations from rotting wood, decaying leaves, a beaver dam and lodge, a woodpile, twigs and roots, and tree bark have been reported. There may be an association of the organism with animal excreta; the fungus has been isolated from soil in chicken houses, from an abandoned mule stall, and from pigeon manure. Recovery of B. dermatitidis also has been documented from both the respiratory tract and feces of a dog with clinical disease, which suggests that yeast-phase cells may be recovered from the stool of dogs with pulmonary blastomycosis follow-ing transit through the gastrointestinal tract of swallowed infected sputum.

Several epidemiologic studies of canine blastomycosis have been conducted. Risk groups include sexually intact males ages 2 to 4 years, large breeds, especially sporting or hound, and young, geriatric, or immunocompromised dogs. Other risk factors are residence in the southeastern, south-central, and upper Midwestern regions of the United States and proximity to river valleys or lakes. The highest risk for blastomycosis is in late summer, autumn, and early winter, which may reflect suitable temperatures for mycelial growth in the environment. The seasonal distribution may also reflect increased outdoor activity of animals during these times, and heat stress and an increase in dusty conditions may represent additional risk factors. In areas with endemic blastomycosis, infections in dogs can signal an increased riskfor human infection. Whereas the prevalence of clinical versus subclinical disease in the dog is unknown, the incidence in dogs has been estimated to be approximately 10 times higher than in humans.

The prevalence of blastomycosis is lower in cats than in dogs. The disease is similar to that in dogs, being characterized by pyogranulomatous inflammation of an isolated organ system or as a multiorgan systemic disease. The lungs and eyes are the most commonly affected sites, and many infected cats have pulmonary lesions regardless of the other organs involved. Clinical signs consist of nasal discharge, cough, lethargy, and weight loss.

Diagnosis

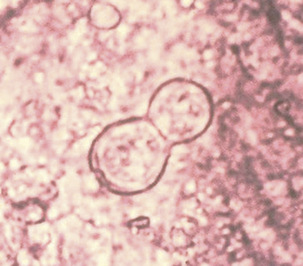

In most animals, blastomycosis can be presumptively diagnosed by cytologic evaluation, which is based on finding the characteristic yeast form in preparations from fine-needle aspirates or touch preparations, and recovery of the fungus from clinical materials. Specimens suitable for disease diagnosis are exudates from draining tracts and lesions, transtracheal washes, fluid from the anterior chamber of the eye, prostatic fluid, and lymph node aspirates. The yeast ranges from 5 to 20 μm in diameter, is unencapsulated, and has a thick refractile, double cell wall (Figure 47-3).

FIGURE 47-3 Smear from a foot lesion of blastomycosis demonstrating budding yeast.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #479, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, date unknown.)

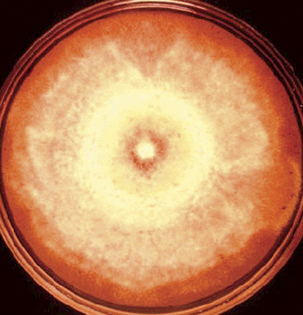

Blastomyces dermatitidis does not remain viable for lengthy periods in clinical materials, so fungal cultures should be initiated immediately when blastomycosis is suspected. The yeast form, and in some strains the mycelial form, is sensitive to cycloheximide, so fungal media with and without cycloheximide should be used. Generally the fungus matures within 2 weeks, but it is recommended to hold cultures for 8 weeks before discarding them as negative. At 25° to 30°C, the mycelial form is quite variable. Colonies range from flat and glabrous to cottony white or tan, and may have concentric rings (Figure 47-4). Visible spicules, consisting of aerial mycelia, may be evident within 1 week. Older cultures become brownish tan with a reverse tan pigment. The mycelial form is extremely infectious and great caution should be exercised when handling cultures. Plates should be examined in a biological safety cabinet.

FIGURE 47-4 Plate with mycelial growth of Blastomyces dermatitidis.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #490, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, date unknown, Libero Ajello.)

COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

Coccidioidomycosis affects numerous mammalian species and is caused by the dimorphic fungus Coccidioides immitis. It has the reputation as the most virulent fungal pathogen. Posadas and Wernicke reported the first case of human disease in 1892, and at the time believed the causative agent to be a coccidian parasite. The true nature of C. immitis was not elucidated until 1900, and the original taxonomic reference has been carried through into today’s name for the genus. Coccidioidomycosis has been referred to in the literature as San Joaquin Valley fever, Valley fever, desert disease or rheumatism, and Posadas disease. The U.S. government has classified this fungus among its select agents as a potential tool of bioterrorists.

Disease and Epidemiology

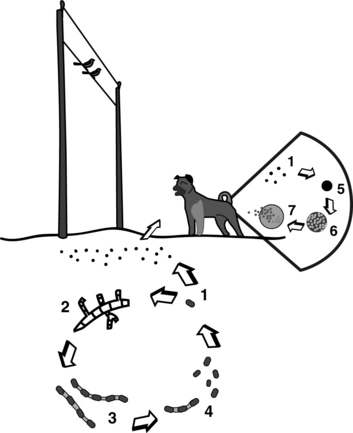

As a dimorphic fungus, Coccidioides spp. have an environmental or saprobic form and a parasitic tissue form. The mycelial form exists in the soil and is undetectable during the wet winter and spring, but actively grows in the upper layers of the soil during a hot, dry summer (Figure 47-5). Growth in the soil is directly affected by competition with other microorganisms. Penicillium janthinellum and Bacillus subtilis, which proliferate duringthe rainy season, appear to be important inhibitory organisms. Hyphae produce infective arthrospores that become aerosolized in the late summer and fall during dust storms or excavation. Winds may carry arthroconidia up to 400 miles from their point of origin. The fungus survivesin rodent burrows, and rodents can apparently distribute it in the environment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree