Chapter 46 The Subcutaneous Mycoses

Subcutaneous mycoses comprise a broad range of infections that involve the deeper layers of the skin, muscle, bone, or connective tissue. Common themes include typical association with injuries, etiologic agents usually found in soil or decaying vegetation, and infections of a chronic and insidious nature. The organisms establish themselves in the skin and produce localized infection of the surrounding tissues and lymph nodes; dissemination is rare. Organisms causing subcutaneous mycoses are dematiaceous or hyaline molds and dimorphic fungi, and the common diseases are sporotrichosis, epizootic lymphangitis, chromoblastomycosis, eucomycotic mycetoma, phaeohyphomycosis, and bovine nasal granuloma.

DISEASE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Feline sporotrichosis develops mainly in intact male cats that are allowed to live outdoors. Initially, lesions appear as small, draining puncture wounds and are commonly seen on the head or at the base of the tail. As the disease progresses, the lesions may become nodular, granulomatous, ulcerative, or necrotic, and systemic spread has been reported.

DIAGNOSIS

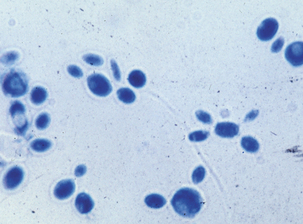

Sporothrix schenckii forms colonies in 2 to 7 days on Sabouraud dextrose agar at room temperature. The mold colonies are cream colored, wrinkled, and leathery, and turn black or silvery gray with age (Figure 46-1). Microscopically, the mold appears as small, oval, hyaline, or dematiaceous conidia. These are arranged singly along the hyphae, or as “flower petals” at the end of short unbranched conidiophores (Figure 46-2). Conversion from the mold to the yeast phase is required for identification. The mold is plated on brain-heart infusion agar supplemented with 5% blood and incubated at 37° C in 5% to 7% CO2 for 3 to 5 days. Yeast colonies are soft and white to cream colored (Figure 46-3).

FIGURE 46-1 Agar plate culture of Sporothrix schenckii, incubated at 20° C.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #3196, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 1969, William Kaplan.)

FIGURE 46-2 Micrograph of conidia of yeast phase of Sporothrix schenckii.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #3063, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 1964, Lucille K. Georg.)

FIGURE 46-3 Slant culture of yeast colonies of Sporothrix schenckii.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #3062, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 1964, Lucille K. Georg.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree