Chapter 48 The Opportunistic Mycoses

Infection is a rare consequence of environmental exposure of animals to normally nonpathogenic fungi. Natural resistance to most of these agents is high, and most are of low virulence. However, agents of low virulence may act as pathogens when animals become stressed or otherwise debilitated, are treated with antibiotics, or following breakdown of the mucocutaneous barrier. Opportunistic fungi (a categorization without taxonomic standing) take advantage of these situations and cause infections. Most opportunistic mycoses are attributed to Candida and Aspergillus spp., and members of the class Zygomycetes.

THE GENUS CANDIDA

Diseases and Epidemiology

Gastroesophageal candidiasis, in association with gastric ulceration, has been described in foals and calves. Animals present clinically with signs of colic that are nonresponsive to medical treatment. Candida albicans or Candida krusei has been recovered from cultures of gastric fluid. Stress is an important predisposing factor.

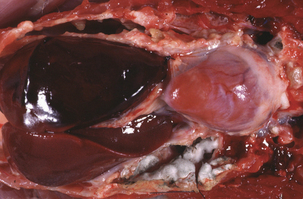

Crop mycosis (“thrush”) of poultry is caused by C. albicans, and serious outbreaks have been reported in many species of birds. The crop, mouth, esophagus, proventriculus, and gizzard are most frequently affected, and lesions consist of white plaques or pseudomembranes adherent to the mucosal surfaces (Figure 48-1, A). Superficial ulcers occur when plaques slough, and mortality may be high in young birds. Disease is frequently associated with other debilitating conditions such as intestinal coccidiosis or unsanitary, crowded housing.

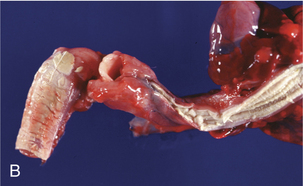

FIGURE 48-1 A, Crop mycosis caused by Candida sp. in a cockatiel. B, Esophageal candidiasis in a javelina.

(Courtesy Gregory A. Bradley.)

The agent of candidiasis in swine is also C. albicans, and disease is associated with stress or immunosuppression and unsanitary housing conditions. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous disease has been described. Circular skin lesions are covered with thick, gray exudates, and alopecia may be apparent. In chronic infections the skin may become wrinkled and thickened. The lesions of mucocutaneous disease are similar to those observed in poultry, and are characterized by pseudomembrane formation. Similar gross lesions can be found in the javelina (Figure 48-1, B).

Diagnosis

Isolation of Candida spp. from clinical specimens does not confirm candidiasis as the diagnosis. The yeasts must be demonstrated either in a direct examination of lesion material or in tissues through histologic evaluation.

Candida spp. grow readily on a variety of nonselective fungal agars, such as Sabouraud dextrose or potato dextrose agars. Colonies are formed within 2 to 3 days at 25° to 30° C and are creamy, white, opaque, and circular (Figure 48-2). Yeast identification is based on microscopic morphology of organisms cultivated on cornmeal-Tween agar; on production of pigment, germ tubes, and urease; and assimilation and fermentation of carbohydrate.

Presumptive differentiation of C. albicans from other Candida spp. involves the germ tube test. The test is performed by placing several colonies from a nonselective fungal medium in animal serum and incubating at 37°C for 3 hours. Microscopic examination reveals short hyphal segments without constrictions, at the junction of the blastoconidium and the germ tube, in positive strains (Figure 48-3). Not all C. albicans strains produce germ tubes, so false negatives may occur.

FIGURE 48-3 Germ tube production by Candida albicans.

(Public Health Image Library, PHIL #1214, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 1967, Lucille K. Georg.)

THE GENUS ASPERGILLUS

Disease and Epidemiology

Human aspergillosis in the United States is the second most common fungal disease requiring hospitalization (after candidiasis). Single isolations of Aspergillus spp. from humans may be insignificant, but multiple positive cultures from immunocompromised individuals suggest invasive aspergillosis. Risk factors include leukemic granulocytopenia, corticosteroid or other drug therapy, smoking marijuana, and posttransplant neutropenia.

Fungi are introduced into poultry houses through spore-contaminated feed or litter. Fungi multiply rapidly under conditions of high humidity, and massive spore inhalation results in acute outbreaks of severe disease associated with high morbidity and mortality. Aspergillosis is sometimes referred to as “brooder pneumonia.” Early lesions consist of small, caseous, white to gray nodules in the lungs or air sacs. Rapid fungal proliferation may line the air sacs with characteristic green hyphae. Acute aspergillosis occurs mainly in poults or chicks, and affected birds are dyspneic, anorexic, and febrile; death is rapid, usually within 48 hours. Chronic disease is seen in older birds, with clinical signs such as coughing, sneezing, ataxia, torticollis, corneal opacity, and emaciation. Trachea and bronchi may be filled with caseous exudate, and white to yellow circumscribed nodules may be visible in the brain. Although the respiratory system is the primary target, other manifestations include dermatitis, osteomycosis, ophthalmitis, enteritis, and encephalitis (Figure 48-4). Aspergillus fumigatus and A. flavus are the etiologic agents most often recovered from lesions.

Canine cutaneous disease with A. niger and Aspergillus terreus is uncommon and poorly characterized. Cutaneous lesions may result either from an extension of systemic disease or through inoculation during skin trauma. Immunodeficiency is an apparent predisposing factor in humans because disease seems to be most common in burn victims, neonates, transplant recipients, and individuals with cancer and AIDS.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of gastrointestinal infections is complex and multifactorial, and is affected by a variety of predisposing factors. Mycotic gastritis often follows injury to the gastric mucosal surface. In young calves, mucosal ulceration related to early ingestion of roughage and infection with bovine rhinotracheitis virus is an initiating factor. Prophylactic and therapeutic use of antibiotics in feed may be an additional risk factor. Mycotic rumenitis and omasitis are linked to the ingestion of moldy feed or hay, and have been described as sequelae to gastritis caused by grain overload. Normal flora of the forestomachs is altered and dietary carbohydrates serve as a source of nutrition for fungal proliferation. Decreased pH leads to erosion and ulceration of the mucosal epithelium, allowing fungal invasion. Penetration of the vasculature leads to thrombus formation and circulatory obstruction, with infarctions and necrosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree