Chapter 23 THE NEWBORN FOAL

A normal healthy full-term foal should be energetic and the following events should occur post-partum (Box 23-1). Foals are usually able to obtain sternal recumbency within about 5 minutes of birth. They should have a strong suckle reflex within 20 minutes and stand within an hour (range:15–165 minutes). They usually start to make attempts to stand within 15–30 minutes, but occasionally a normal foal may take as long as 2 hours to successfully get and stay standing and nurse. The first few attempts to stand may be uncoordinated and aimless, but they should figure it out with minimal assistance. The longer it takes, the greater the chance there is a problem with the foal and veterinary assistance will be required. If the foal has not suckled within 4 hours, it should be considered abnormal. Anything that varies from these guidelines should be considered abnormal and veterinary care should be sought prior to the routine veterinary check. The chance of a positive outcome increases the sooner veterinary intervention is made.

Box 23-1 Normal Post-Partum Foal Events

Standing within 15 minutes to 2 hours

Consider the foal abnormal if it has not stood and suckled in 4 hours.

RISK ASSESSMENT

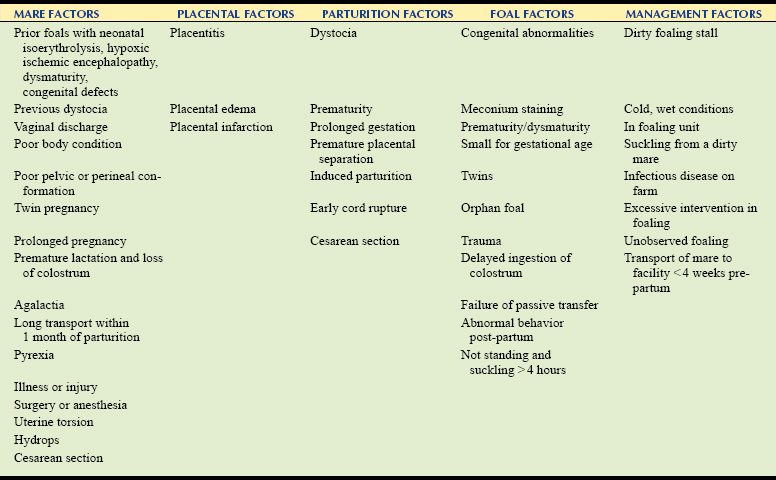

The use of risk categories can improve the outcome of serious complications in neonatal foals by allowing for early monitoring, assessment, and intervention. These categories can be used to guide management practices and determine the amount of intervention needed and the need for the presence of a veterinarian at the time of parturition. The three-category system (low, moderate, and high risk) has been used successfully.1–3 A two-category system has also been suggested that eliminates the moderate category and therefore allows more foals to be classified as high risk and receive more attention.4 In determining the risk category of the foal, several factors are assessed, including the mare’s reproductive history, maternal conditions during the pregnancy, ease of birth, management and environmental factors, and the foal’s condition (Table 23-1). The risk category of the foal can be changed at any stage such that a foal that was considered “low risk” pre-partum suddenly becomes a “high risk” foal if a dystocia is encountered, or the foal is found to have an abnormality on assessment.

If the foal has only one factor in the high-risk group, it is classified as “moderate risk.” Foals classified as a “high-risk” prepartum can be decreased to moderate if the parturition is normal and the foal appears clinically normal. Increased observation is still warranted and many recommend placing these foals on broad-spectrum antibiotics with a good gram-negative spectrum (e.g., ceftiofur) for the first 48–72 hours of life.1 Serial blood work should be performed in these foals over the first week of life. This would include testing for passive transfer of immunoglobulins (IgG), a complete blood count, and biochemistry profile. The foals should be monitored closely for energy, suckling, and weight gain. “Low-risk” foals are those with no identifiable abnormalities in any category and are basically normal foals in all regards.

Maternal factors include a combination of historical data regarding reproductive history, such as uterine infection, previous foalings, and illness of the mare during the pregnancy. Maternal risk factors include any factor that may interfere with the development or nourishment of the foal in utero or that interferes with the mare’s ability to supply an adequate amount of good quality colostrum.1,5 Examples of such conditions would include prior foals with neonatal isoerythrolysis (NI), hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, dysmaturity, congenital defects, or poor-performance of undetermined cause, prior dystocias, twin pregnancies, premature lactation, or illness in the mare, among other things. Placental abnormalities such as placentitis, edema, or other placental irregularities can be identified pre-partum via ultrasound examination or post-partum by examination of the placenta, and they will increase the risk for the foal. Foals that are determined pre-partum to be at a “high risk” may be foaled out at a center that provides close monitoring and immediate veterinary attention at the time of parturition.

Even though a mare and her gestation had seemed normal, any problems with the parturition process affect the foal’s risk category by potentially altering blood flow or causing direct trauma to the foal.1,5 Some of the conditions affecting the foal may be very obvious, such as dystocia, whereas others may be more subtle or unobserved. Any foal resulting from an unobserved delivery should be treated as “high risk” until determined otherwise. The same holds true for premature deliveries, premature placental separation, cesarean sections, or induced parturitions.

INITIAL FOAL ASSESSMENT

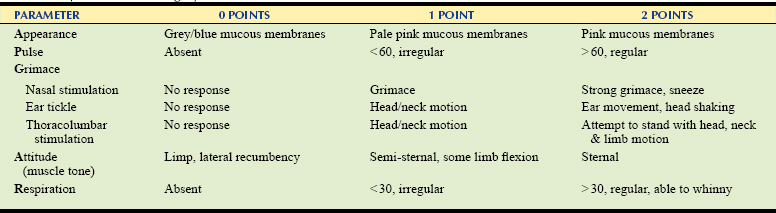

All those attending foalings should be instructed on how to perform an immediate post-partum evaluation of the foal using the APGAR scoring system described in Table 23-2, or some modification thereof, to assist with recognition of early signs of problems and to determine the need for additional assistance and intervention.3 This scoring is easy to perform even by inexperienced staff and should be obtained within the first 10–15 minutes post-partum. Each parameter is scored from 0 to 2. An optimal total score is 10, with normal foals usually scoring 9 or 10. Foals that score between 6 and 8 are usually considered to have mild asphyxia and may improve with stimulation by rubbing the core and limb manipulation. Assisting the foal into sternal recumbency may also be of benefit. Foals that score between 3 and 5 usually require oxygen therapy and cardiovascular support in addition to stimulation and placement in sternal recumbency. Preparations for intervention with respiratory and cardiovascular resuscitation should also be made. Aggressive therapy is usually required for foals that score <3, since full resuscitation is usually required.3

Vital Parameters

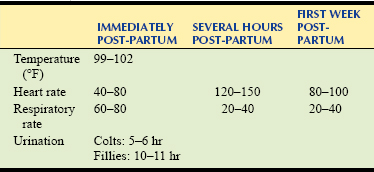

There are many immediate post-partum changes that will affect the foal’s physical examination findings (Table 23-3). Most of these changes are due to accommodation of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems to life outside of the uterus. The pulse (HR) should be 40–80 bpm soon after birth and then increase to >100 bpm within the first hour of life. This increase usually coincides with the foal attempting to stand. It should take its first breath rather quickly after delivery, usually within the first 30 seconds. There may be an initial series of gasps that quickly change to a more normal breathing pattern. The respiratory rate (RR) should be >30 breaths/min and shallow just after birth. A slow RR is of more concern than a more rapid rate and may indicate the need for intervention and possible resuscitation.

Prematurity/Dysmaturity

An assessment of the foal’s readiness for birth is also important in its initial assessment. Caretakers should be familiar with the signs of prematurity/dysmaturity as described in Box 23-2 in order to address the problems and potential complications that these foals may encounter. Prematurity should be assessed in each foal with a combination of the clinical appearance of the foal and the length of gestation. The presence of such signs warrants that the foal be treated as a “high-risk” foal and should be examined by a veterinarian before the routinely scheduled examination. Problems with premature/dysmature foals may include a variety of respiratory, metabolic, and infectious diseases.

Immaturity in the musculoskeletal system includes joint laxity, flexor tendon laxity, and incomplete ossification of the cuboidal bones of the carpus and tarsus. Immature foals have a characteristic short, silky hair coat (Fig. 23-1). The hair matures from cranial to caudal and therefore the hair over the back and rear quarters will be the most immature. They can have a domed forehead, bulging eyes, soft lips, a deep red tongue, and floppy ears (Fig. 23-2). Immature foals will frequently have altered thermoregulation, so extra nursing care is required to prevent hypothermia (Fig. 23-3).

POST-PARTUM CARE

Resuscitation

There are many causes of asphyxia in the foal, including maternal issues (e.g., systemic disease, hypotension, general anesthesia), placental abnormalities (e.g., placentitis, placental insufficiency), or fetal diseases (e.g., immaturity, infection, cardiac disease, umbilical cord compression). In addition, the delivery itself may be associated with asphyxia caused by dystocia, premature placental separation, or inappropriate positioning of the mare for delivery. When confronted with a lack of oxygen, the foal can start to breath in utero, which will result in complications such as meconium aspiration and reversion back to the fetal circulation. This will result in apnea when the foal is born. Resuscitation is required for any foals that are apneic or experiencing very low RRs (<10 breaths/min) or are gasping. Resuscitation is also in order should the pulse be absent or the foal flaccid and non-responsive. A prepared kit should be easily accessible that contains all that is required to allow for resuscitation (Box 23-3).

Box 23-3 Foal Resuscitation Kit

The approach to resuscitation should include a thorough assessment of the foal, followed by clearing of the airways. If the foal has just been delivered, the amniotic membranes must be removed from the nostrils. Any secretions in the airways should be removed by positioning the head down, gentle pressure on the chest, and suctioning of the fluid from the nasal passages and pharynx. Attempts should be made to stimulate the foal to breathe by rubbing the foal briskly with towels, tickling the nasal mucosa or ear canal, flexing the limbs, or gently compressing the chest wall. The controversial use of doxapram (0.5 mg/kg IV) may be attempted. If a veterinarian or trained staff is present, the foal should be intubated (7-9–mm nasotracheal tube). Alternatively, a mask can be used to administer oxygen and breaths safely. Positive-pressure ventilation can be administered with the use of several devices. Care must be taken when using an Ambubag since a full compression is about 1 L, which would be too much for most foals. With 100% oxygen attached to the system, the inspired air has about 21% oxygen. Another easy-to-use device that can be used with or without oxygen is the C.D. Foal Resuscitator (Fig. 23-4). This unit contains two plastic cylinders that draw air through the induction valves and then expel it to the foal via a face mask. It has a bi-directional mask that allows the foal to exhale without removing the mask. It also has an adapter so that it can be used to aspirate fluid from the airways before resuscitation. If no units are available, positive-pressure ventilation can also be achieved by mouth-to-tube/nostril. If a demand valve is used in a clinic setting, care must be taken not to apply too much pressure. A breath should be administered just long enough to see the chest start to rise before being released immediately.

Umbilical Care

The umbilicus usually ruptures within 6–8 minutes of birth about 3–5 cm from the body wall. Concern over premature rupture of the chord and the loss of blood were not clinically significant.6 Using umbilical clamps can increase the chances of urachal and umbilical infections. The stump should be treated as soon as possible after the chord has ruptured. The use of chlorhexidine (0.5%) solution is preferred and appears to be superior to 2% iodine or povidone-iodine in decreasing the incidence of umbilical infection.1,7 The stump should be treated every 6 hours for the first 24 hours and then continued based on need (e.g., recumbent foals may require prolonged treatment). The use of 7% iodine is discouraged since it is too caustic and can cause necrosis of the surrounding skin predisposing the foal to infections and patent urachus. The powdered preparations do not likely penetrate into pits in the skin and are not as effective as a solution. Therefore, dipping the stump into the solution is preferable. Solutions should not be used on multiple foals; each foal should have its own dip. To make the chlorhexidine solution add 1 part 2% chlorhexidine solution to 3 parts sterile water. This solution will not dry up the stump as quick as the iodine solutions. If more desiccation is desired, a small amount of alcohol can be added to the mixture (about 10% of the total volume).

Prophylactic Enemas

Meconium is the first feces that the foal must pass and is usually dark, firm, and pellet like. It can also appear as tarry, soft, sticky feces that can vary from dark brown to green. It is made up of digested amniotic fluid, mucus, epithelial cells, and bile. Should it be passed in utero, it is an indicator of fetal stress and the risk of pneumonia resulting from meconium aspiration is great and these foals should be treated as “high-risk” foals. All the meconium should normally be passed within 24 hours post-partum. The majority of foals pass it within 4 hours. Once the yellow milk feces are passed, the meconium can be deemed completely eliminated from the intestinal tract. Meconium impactions are the most common cause of colic in neonatal foals, and colts have a higher incidence than fillies, especially when considering impactions in the pelvic inlet.1 Foals that have had prolonged gestations tend to have a higher incidence of meconium impactions.

Colostrum Intake

Foals are born agammaglobulinemic and immunologically naïve but are immunocompetent.8 Therefore, they rely on the immunity imparted by the colostrum to fight infection for the first 4–9 weeks of life. The foal’s IgG concentration is a major factor in preventing infection in the neonates and therefore much attention is paid to ensure that the foal receives and absorbs adequate amounts.9–11 When a foal fails to absorb sufficient maternal antibodies, it results in FPT. The commonly accepted value for FPT is any serum concentration that is below 400 mg/dL, while concentrations between 400 and 800 mg/dl are considered partial FPT.12,13 Foals with FPT have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality because of septicemia, and early intervention and treatment with antibody supplementation helps to improve the outcome.11,14

Any foal that fails to suckle colostrum within the first 4 hours should be considered abnormal, and immediate intervention is recommended to get the colostrum into the foal (tube/bowl/bottle). Each foal should suckle at least 1 L of good-quality colostrum to provide adequate protection. Intervention is also in order should the colostrum itself not appear normal in character or quantity. Therefore, checking the colostrum and double-checking the foal’s IgG absorption are imperative. Normal colostrum is creamy yellow and sticky. The quality of the colostrum depends on the IgG content. Generally an IgG concentration in the colostrum >70 g/L is considered adequate. This concentration of IgG is associated with a specific gravity >1.060 on a colostrometer or refractometer.15 On a refractometer for measuring sugar concentrations, it should be at least 20%.16 Special attention should be paid to the colostrum of maiden or older mares, mares with a history of poor colostrum production in the past, premature deliveries, or if the mare has been leaking colostrum before foaling. The easiest, although not very accurate, way to assess the colostrum is with its physical appearance. If it is white or dilute, it is definitely not adequate.

ROUTINE VETERINARY EXAMINATION

Routine veterinary physical examinations are important to identify “high-risk” foals, formulate a list of differential diagnoses, direct ancillary tests, arrive at a presumptive diagnosis, and formulate a plan for initial therapy. Repeated veterinary examinations on subsequent days would be ideal and are commonly undertaken on large breeding farms. A foal’s condition can change rapidly; it can appear normal during the veterinary examination and then within a few hours be severely compromised. Therefore, frequent examinations by the caretakers are recommended. When only a single veterinary examination is scheduled, it is usually performed between 12 and 18 hours of life to allow for assessment of colostral absorption at the same time. Assessing and addressing emergencies will take priority in the examination. In emergency situations, the major focus of the examination should involve evaluation of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. Otherwise, a full detailed veterinary examination should be performed on all foals, even if they appear normal to the caretakers. Sick foals should have a sepsis score performed. This is a scoring system designed by Brewer and Koterba10 to predict infection based on certain aspects of history, clinical pathology, and clinical examination. Points are assigned to the neutrophil count, the band neutrophil count, the presence of Döhle bodies, toxic granulation or vacuolization in neutrophils, and the fibrinogen concentration.10 Other laboratory data that are scored include the presence of hypoglycemia, the IgG concentration, arterial oxygenation, and the presence of metabolic acidosis.10 The clinical examination focuses on the presence of petechiation or scleral injection that is not a result of trauma, fever, hypotonia, coma, depression, or seizures as well as the presence of uveitis, diarrhea, respiratory distress, swollen joints, and open wounds.10 Historical data of concern include placentitis, the presence of vaginal discharge, and dystocia.10 The identification of prematurity on this scoring system is based on days of gestation alone.10

Every veterinary examination should start with observation of the foal’s behavior from afar, assessment of the environment, and a critical history related to the mare, the gestation, the delivery, and the post-partum events, including the quality and quantity of colostrum consumed. The examination of the foal is incomplete without the examination of the mare and the placenta. Critical assessment of the foal’s behavior can be useful to identify problems, or merely to identify that there is something not quite normal with the foal and therefore closer attention and more frequent examinations are warranted. This can include both the way the foal responds to the mare as well as how it interacts with its environment. The behavior of the mare can also be of importance, especially when rejection is a possibility or she is too anxious to allow the foal to suckle adequately. The frequency, efficiency, and vigor at which the foal suckles are also of importance (Fig. 23-5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree