Chapter 13

The Musculoskeletal System

Bone

Inflammatory Diseases

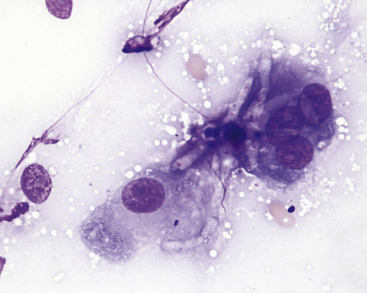

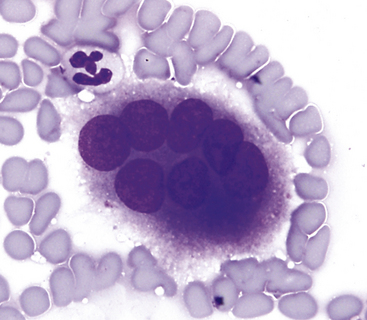

Osteoclasts may also be found in small numbers in specimens from inflammatory lesions. These cells resemble multinucleate giant cells and arise from precursor cells of the monocyte–macrophage cell line. They are very large and irregularly shaped with variable numbers (typically 6 to 10) of uniform, round nuclei arranged randomly throughout the cell and abundant, light blue cytoplasm (Figure 13-1).

Figure 13-1 Osteoclast with multiple, relatively uniform nuclei and abundant cytoplasm from a lytic bone lesion. (Wright stain.)

Bacterial osteomyelitis typically results in a neutrophilic or suppurative inflammatory response. Some specific causes of bacterial osteomyelitis include Actinomyces spp. and Nocardia spp., and these are often seen as branching, filamentous rods. Staphylococcal, streptococcal, and gram-negative aerobic bacterial infections are common and may be identified on cytology.1

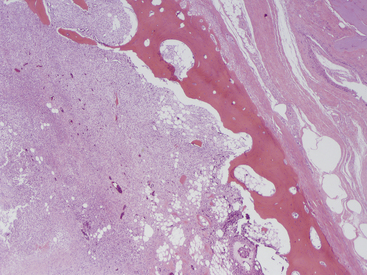

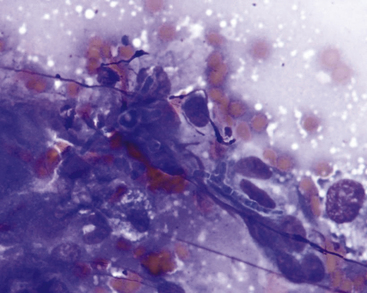

Osteomyelitis may also be seen with fungal infection, and the organisms may be detected in the exudate. The exudate with fungal infections is typically more mixed than that in bacterial infections and often contains a much larger component of activated macrophages and multinucleate giant cells. Fungal organisms include Coccidioides immitis, Blastomyces dermatitidis, and Histoplasma capsulatum. Hyphating fungal organisms such as Aspergillus spp. and Geomyces spp. may also be seen and appear as staining or nonstaining fungal hyphae (Figure 13-2 and Figure 13-3).2 Rarely, protozoal organisms such as Hepatozoon spp. may be seen as gamonts within the neutrophils in inflammatory aspirates of bone.3

Figure 13-2 Fungal hyphae from lytic bone lesion in a dog.

Aspergillus was cultured from this lesion. (Wright stain.)

Neoplastic Diseases

Neoplasms of bone are relatively common in domestic animals, and cytologic examination is useful in establishing the diagnosis in some of these diseases. As with the interpretation of histologic sections of bone, evaluation of cytologic specimens from bone requires knowledge of the clinical and radiographic features of a specific lesion. Cytology is probably more useful in distinguishing inflammatory bone disease from neoplasia than in identifying specific bone tumors; however, osteosarcomas and chondrosarcomas do have characteristic cytologic features that aid in diagnosis.

Special stains are available to differentiate osteosarcoma from other mesenchymal neoplasms of the bone. Nitroblue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate toluidine salt (NBT/BCIP) may be used to detect alkaline phosphatase activity in osteoblasts.4 Because both reactive and neoplastic osteoblasts will stain positive, previous diagnosis of malignancy based on identification of criteria of malignancy on cytologic exam is necessary. Both unstained slides and prestained slides (aqueous Romanowsky method only) may be used.5

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone tumor typically affecting the appendicular skeleton. In the dog, osteosarcoma occurs more commonly in the front limbs with the distal radius and proximal humerus as the most common sites (Figure 13-4).6 Aspirates of osteosarcomas are often more highly cellular compared with aspirates of soft tissue sarcomas. Cells may occur individually or in aggregates. One characteristic feature that may be evident on low-power examination of the slide is the presence of islands of osteoid surrounded by tumor cells. Osteoid (Figure 13-5 and Figure 13-6) appears as a somewhat fibrillar, bright-pink material on Wright-stained slides. These structures are not found in most aspirates from osteosarcomas; however, when found, their presence provides strong evidence that the origin of a tumor is bone. Individual tumor cells vary from round to plump to fusiform and often vary greatly in size (Figure 13-7). They often have many of the classic cytologic features of malignancy such as karyomegaly, anisokaryosis, large nucleoli, and multiple nucleoli that differ in size. The cytoplasm is typically dark blue and may contain several clear vacuoles (Figure 13-8). A proportion of the cells from most osteosarcomas contain scattered, pink cytoplasmic granules (Figure 13-9). These granules are not specific to osteosarcomas; similar granules may also occur in cells from chondrosarcomas and, less commonly, from fibrosarcomas. Cells from more differentiated osteosarcomas (Figure 13-10) are more uniform and may be difficult to distinguish from normal osteoblasts. Small numbers of inflammatory cells, nonneoplastic osteoblasts, and osteoclasts similar to those described in the previous section on inflammation may also be found in aspirates from osteosarcomas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree