Chapter 22

The Kidneys

Cytologic examination (e.g., fine-needle aspiration [FNA]) is a useful tool in diagnosing certain renal lesions, especially neoplasms, in dogs and cats. The advantages and disadvantages of FNA (cytology) compared with incisional biopsy (histopathology) of the kidney are presented in Table 22-1. Although the examination of cytologic specimens does not provide the cellular architecture necessary to characterize many lesions in which structural relationships are important, it may sometimes provide sufficient diagnostic information to aid in the clinical management of cases and is less invasive and associated with fewer complications compared with full tissue biopsy. Major complications resulting from FNA of the kidney are relatively uncommon if appropriate procedures are followed.1

TABLE 22-1

Advantages and Disadvantages of Renal Cytology Compared with Incisional Biopsy

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Less invasive, fewer complications | Does not allow for assessment of tissue architecture |

| Less expensive | Does not allow for evaluation of glomeruli |

| Rapid diagnosis of some conditions such as feline lymphoma | Blood contamination and low cell yield often limit usefulness |

Disease conditions that are most likely and least likely to yield diagnostic cytologic results are presented in Box 22-1 and Box 22-2. The primary indication for FNA is abnormally sized or abnormally shaped kidneys. Cytologic specimens from patients with unilateral or bilateral renomegaly are most likely to yield diagnostic information; small or shrunken kidneys rarely yield positive diagnostic findings. Either fluid or solid tissue lesions may be encountered, and the results of cytologic analysis may help characterize the process as cystic, inflammatory, or neoplastic. Renal cytology is especially useful for the rapid confirmation of renal lymphoma in cats. Although positive cytologic findings are useful in establishing a diagnosis, tentative diagnoses cannot always be excluded on the basis of negative findings because representative material may not have been recovered during collection attempts.

Collecting adequately cellular specimens for evaluation is a limiting factor of renal cytology. FNA of the kidney is easier in cats because their kidneys are more easily palpated and immobilized against the body wall. Using ultrasonography to detect optimal sites for specimen collection and to provide additional information about the nature and extent of lesions may significantly increase diagnostic yield. Because of the highly vascular nature of the kidneys, blood contamination is a significant problem during sample collection. Use of a nonaspiration (i.e., capillary action) technique (see Chapter 1) facilitates the collection of cellular specimens that are not heavily contaminated with blood. Highly cellular, solid lesions (e.g., neoplasms) are also more likely to provide cellular samples than many degenerative or inflammatory diseases.

Sampling Technique

FNA is associated with less tissue trauma compared with punch biopsies, and contraindications for collecting cytologic specimens from the kidneys are only a few. Contraindications for renal FNA are listed in Box 22-3. As with other renal biopsy procedures, the main complication is excessive hemorrhage.1 Patients should be evaluated for the presence of coagulation defects prior to the procedure; adequate restraint is necessary to prevent unexpected movement during the procedure, and the kidney must be adequately immobilized against the body wall. Seeding of the needle tract with neoplastic cells during fine-needle sampling of malignant lesions has been suggested as a complication; however, clinical experience and results of retrospective studies in humans show such seeding to be uncommon.2,3

The skin at the site is clipped and prepared as for surgery. The patient is usually restrained in lateral recumbency, and the kidney is manually immobilized against the body wall. As mentioned previously, a nonaspiration technique is preferred to limit the amount of blood contamination.4 A 22- or 23-gauge needle attached to a 10- to 12-milliliter (mL) syringe that has been prefilled with air is held at the base of the needle with the thumb and forefinger. Depending on the type of lesion, the needle is directed either into the lesion (focal lesions) or tangentially into the cortex of the kidney (diffuse lesions). Care should be taken to avoid the renal hilus, which contains large vascular structures. The needle is passed through approximately two thirds the thickness of the lesion about five to seven times with a stabbing motion. The repeated needle punctures should be along a single plane (similar to the action of a sewing machine) to minimize blood vessel rupture. Samples may be collected from different portions of the lesion using multiple (two or three) collection attempts. Collection of several slides (at least five) from different areas of the lesion helps increase the chances of obtaining a diagnostic specimen. Whenever blood is visible in the hub of the needle or syringe, collection should be stopped and the material spread onto a glass slide because continued collection attempts usually result in gross blood contamination, rendering the sample worthless.

After collection, the material in the needle (none is usually visible in the syringe) should be carefully dispersed on one end of a glass slide and gently spread out using a slide-over-slide technique (see Chapter 1). If fluid is obtained, direct and line smears should be made, and the remainder of the fluid put into an ethylenetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube. If the fluid is clear (suggesting low cellularity) and sufficient sample has been obtained, concentrated sediment smears, which are similar to urine sediments, are prepared and air-dried.

Cytologic Evaluation

Normal and Abnormal Cell Types Encountered

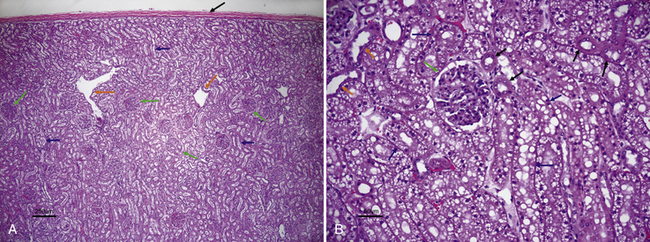

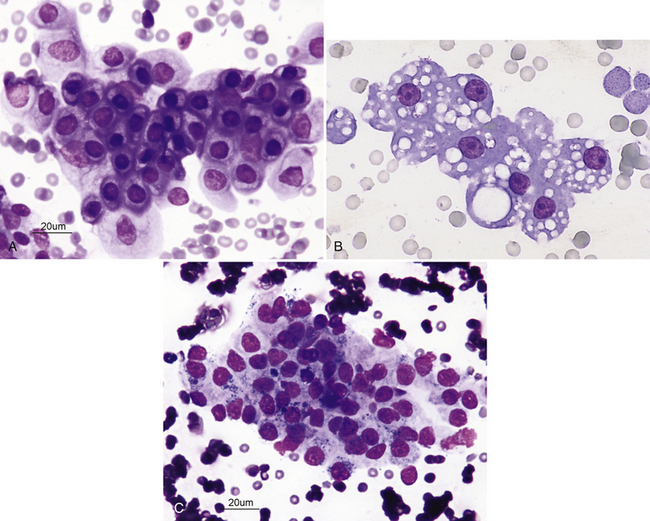

The normal histologic anatomies of the canine and feline renal cortices are shown in Figure 22-1. The renal parenchyma consists of glomeruli, tubules, interstitium, and blood vessels. Renal tubules make up the bulk of the parenchyma. Findings in normal renal aspirates are listed in Table 22-2. Renal tubular epithelial cells are the predominant cell type seen in fine-needle aspirates from normal kidneys. They are rather large, round to polygonal cells that occur singly and in clusters (Figure 22-2, A). They have a round, centrally placed nucleus and abundant light blue cytoplasm, which, in cats, often contains several distinct, clear vacuoles from the presence of lipid droplets (see Figure 22-2, B). Clear cytoplasmic vacuoles may also occur in dogs with diabetes mellitus, long-term exposure to corticosteroids, or lysosomal storage disease (Box 22-4). Cells of the distal convoluted tubules and ascending limb of the loop of Henle may contain dark intracytoplasmic granules (see Figure 22-2, C).3

TABLE 22-2

Findings in Normal Renal Aspirates

| Cell Types or Structures | Appearance | Comments |

| Renal tubular epithelial cell (see Figure 22-2) | Medium to large, round to polygonal cells that occur singly and in clusters; central round nucleus with single visible nucleolus, light blue cytoplasm, which may have clear vacuoles (in cats) | Predominant cell type seen |

| Intact renal tubules (see Figures 22-3 and 22-4) | Densely packed cells as described above arranged in tubular arrays | Variably present |

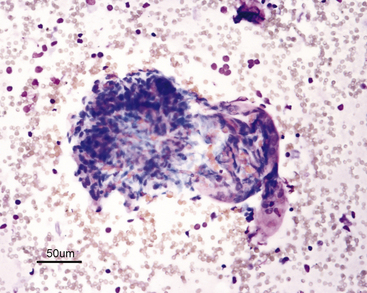

| Glomeruli (see Figure 22-5) | Lobulated clusters of slender, oval to spindle-shaped cells | Infrequently seen |

| Collagen matrix | Strands of homogeneous, acellular pink material | Absent or present in only small amounts; collagen obtained from renal capsule or interstitium |

| Peripheral blood | Many erythrocytes with platelet aggregates and leukocytes (neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes) | Marked blood contamination is common; subjective assessment of types and number of leukocytes present is only way to differentiate blood contamination versus inflammation |

Figure 22-1 A, Histologic section of normal canine kidney. Renal tubules comprise the majority of the normal renal parenchyma. Note absence of vacuoles in the proximal tubular epithelial cells (blue arrows) in contrast to the cat kidney shown in B. Glomeruli (green arrows) are prominent structures in the renal cortex and consist of a tuft of interconnected capillaries enclosed in a capsule named after Bowman. Orange arrows identify dilated intralobular veins. The black arrow identifies the thick fibrous capsule through which the needle penetrates during the fine-needle aspiration procedure. (H&E stain.) B, Histologic section of normal feline kidney. Note prominent lipid vacuolation of proximal tubular epithelial cells (blue arrows). The lipid vacuolation is what accounts for the grossly pale tan-yellow appearance of a normal feline kidney. Note cuboidal cells without vacuoles that line the distal tubules (black arrows) and low cuboidal, nonvacuolated epithelial cells of the collecting duct (orange arrows). The green arrow identifies a glomerulus. (H&E stain.) (A, Courtesy of Dr. Pam Mouser. B, Courtesy of Dr. Pam Mouser)

Figure 22-2 A, Renal fine-needle aspiration (FNA) from a dog. Numerous renal tubular cells showing mature, uniform nuclei with dark, mature chromatin. (Wright-Giemsa stain.) B, Renal FNA sample from a cat. Note the cluster of renal tubular epithelial cells with some blood contamination; feline renal tubular cells are often vacuolated. Nucleoli are visible but are small and round. (Wright stain. Original magnification 330×.) C, Cluster of renal tubular cells from a renal FNA sample from a cat. The cells are mature and uniform and show cytoplasmic granules. (Wright-Giemsa stain.)

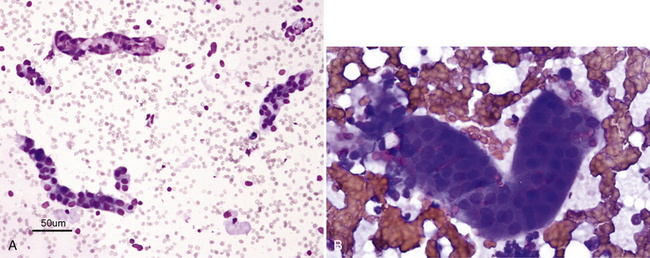

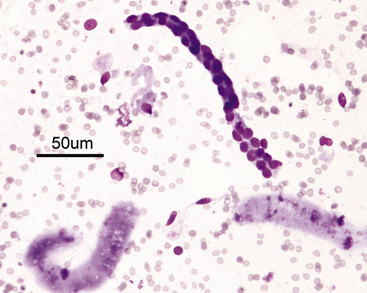

Differentiation of the various epithelial cell types is not practical or of diagnostic importance. The cells and their nuclei should be relatively uniform in size and shape; however, the different types of epithelial cells differ slightly in size. The nucleus-to-cytoplasm (N:C) ratio of normal tubular cells is low, except for feline lipid-laden proximal tubular epithelial cells, and tubular cells that are well spread out often have a single, visible nucleolus (see Figure 22-2). When present, nucleoli should be small and round. Renal tubular cells often remain together as recognizable tubule fragments of various sizes (Figure 22-3). Tubular casts may also be seen in renal aspirates from some animals (Figure 22-4). Their significance depends on the amount and type of cast present, similar to those in urine sediments. Glomeruli may be seen in cellular samples and appear as somewhat lobulated clusters of slender, spindloid cells (Figure 22-5).5 Individual cells are difficult to see because they are tightly clustered. Abnormalities of the glomeruli (e.g., glomerulonephritis) are not readily discernible cytologically and require histologic analysis. A few homogeneous strands of acellular pink matrix (collagen) may be seen in normal renal aspirates. The matrix is typically obtained as the needle passes through the fibrous capsule of the kidney (Figure 22-1, A).

Figure 22-3 A, Small tubular fragments in a renal fine-needle aspiration (FNA) from a dog. (Wright stain. Original magnification 50×.) B, Higher magnification of tubular fragment in a renal FNA from a cat. Dark nuclei of individual tubular cells are visible, but cell margins are difficult to discern. (Wright stain. Original magnification 500×.)

Figure 22-4 A renal tubular fragment and two casts in a renal fine-needle aspiration from a dog. (Wright stain. Original magnification 50×.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree