CHAPTER 17 The Lung and Intrathoracic Structures

Percutaneous transthoracic fine-needle aspirates (FNAs) or fine-needle biopsy (FNB) of the lung and mediastinal masses may be extremely useful in patients with diffuse pulmonary lesions or lung and intrathoracic masses that can be localized radiographically or by ultrasound.1,2 It is a rapid, relatively safe procedure that can be used to collect material for cytologic evaluation and to obtain material for culture (Box 17-1). Neoplasms, hypersensitivity conditions, inflammatory lesions, and specific infectious agents (mycotic, protozoal, bacterial) may often be detected.1–3 In human patients, FNB of the lung is 96% successful in diagnosing malignant neoplasms and 77% successful in obtaining material that yielded an infectious agent from immunosuppressed patients with a focal, pneumonic infiltrate.3

Although FNAs can generally be obtained with little risk, less invasive procedures, such as transtracheal/bronchoalveolar wash, thoracic radiography, and hematologic examination, should be performed first.2,4 Transthoracic pulmonary fine-needle aspiration is contraindicated in animals with bleeding disorders, cystic or bullous lung diseases, pulmonary hypertension, and diseases producing forceful breathing and coughing that cannot be temporarily controlled (Table 17-1).2–4 The procedure is also contraindicated in intractable patients. Hemorrhage, pneumothorax, and/or lung laceration are the primary complications.2–4 In people, tumor seeding along the needle tract after FNB of a pulmonary mass has occurred in a few instances.5

Table 17-1 Contraindications for Fine Needle Aspiration of Lung Parenchyma and Associated Complications

| Contraindication | Complication |

|---|---|

| Uncooperative patient | Lung laceration |

| Uncontrollable coughing or forceful breathing | Lung laceration |

| Any bleeding disorder | Severe intrapulmonary or pleural hemorrhage |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Severe intrapulmonary or pleural hemorrhage |

| Cysts or bullous emphysema | Pneumothorax |

Ultrasonography has become a common tool for assisting collection of cytology and biopsy specimens from lung and mediastinal lesions. It allows sampling of localized lesions and better visualization of lesions that may be difficult to visualize radiographically due to fluid accumulation in the chest.1

If ultrasound guidance is not available, the dorsal portion of the right caudal lobe is the preferred site for aspiration in patients with diffuse lung lesions.3 Because the lung parenchyma is thickest in the caudal lobe, parenchymal aspirates are obtained more easily from this area and the likelihood of penetrating another vital structure is minimized.3

Utilization of ultrasound to visualize lesions and guide in the collection of cytologic and histologic specimens is common. This technique may be especially useful if there is fluid around a visible lesion or if the lesion has contact with the chest wall.7 It is preferred over blind fine-needle aspiration when masses are located near vital structures (e.g., large vessels). In general, sedation is indicated to adequately restrain patients during the procedure. Patient preparation, postaspiration management (e.g., observation), and complications are similar to those described for fine-needle aspiration.7

TECHNIQUE

The technique described later is for non-ultrasound–guided fine-needle aspiration of the lung. The technique for ultrasound guided biopsies is not described in this chapter but can be found in numerous textbooks.1

The area to be aspirated depends on whether the lesion is localized or generalized. If generalized, the needle is inserted on the right side of the chest between the seventh and ninth ribs, two thirds of the way dorsal between the costochondral junction and the vertebral bodies.3 For localized lesions, the area of needle insertion depends on the location of the lesion, which is identified by lateral, dorsoventral, and ventrodorsal radiographs.3

The hair is clipped, the area is scrubbed and draped, and an antiseptic is applied. Local anesthetic may be used if desired but is frequently not needed. Heavy sedation may be required in uncooperative patients; however, sedation should be avoided if possible because sedated patients cannot clear respiratory secretions or endobronchial hemorrhage that may result from the FNB procedure.3

The patient is restrained in the standing, sitting, sternal, or lateral recumbent position. Depending on the animal’s size, a 23- to 25-gauge,  – to 1½-inch needle, with a 10- to 20-ml syringe attached, is inserted aseptically through the chest wall at the cranial aspect of the rib, avoiding the intercostal vessels on the adjacent rib’s caudal border. The nose and mouth are temporarily held closed to stop lung movement while the needle is advanced into the lung parenchyma (about 1 to 3 cm), and negative pressure is applied while the needle is moved back and forth (about 1 cm). Negative pressure is released and the needle is withdrawn. Some authors advocate maintaining negative pressure while the needle is withdrawn to help avoid leaving tissue along the needle tract.2,3

– to 1½-inch needle, with a 10- to 20-ml syringe attached, is inserted aseptically through the chest wall at the cranial aspect of the rib, avoiding the intercostal vessels on the adjacent rib’s caudal border. The nose and mouth are temporarily held closed to stop lung movement while the needle is advanced into the lung parenchyma (about 1 to 3 cm), and negative pressure is applied while the needle is moved back and forth (about 1 cm). Negative pressure is released and the needle is withdrawn. Some authors advocate maintaining negative pressure while the needle is withdrawn to help avoid leaving tissue along the needle tract.2,3

The needle is removed from the syringe and the syringe is filled with air. The needle is reconnected to the syringe and the material in the hub of the needle is forced onto a glass slide, smeared, and stained for cytologic evaluation. Chapter 1 describes general techniques for FNB (aspiration and nonaspiration techniques), slide preparation, and staining. An adequate sample for cytologic evaluation can generally be collected with one or two attempts.

The patient should be closely monitored for post-aspiration complications. Thoracic radiographs, immediately and 24 hours postaspiration, have been suggested.3 Pneumothorax is the most common complication, reported to occur in 20% of patients.8 However, most involve mild asymptomatic pneumothorax, which resolves spontaneously.3 Favorable patient positioning may inhibit pneumothorax progression.6 Rotating the animal so that the lung puncture site is down (dependent position) for 3 minutes markedly decreases pneumothorax formation.6 The clinician should be prepared to insert a chest tube if severe pneumothorax develops.3

CYTOLOGIC EVALUATION

Cell Types of the Lung

Columnar and Cuboidal Cells

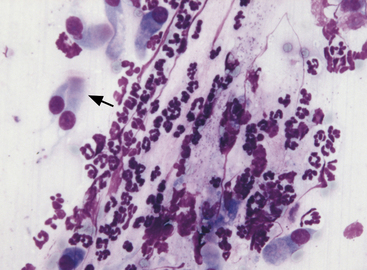

Ciliated columnar cells (Figure 17-1) have an elongated or cone shape, with cilia on the flattened end and the other (basal) end containing the nucleus and often terminating in a tail. The nucleus is generally round to oval, with a finely granular chromatin pattern.9 Ciliated cuboidal cells appear similar to ciliated columnar cells, except cuboidal cells are as wide as they are tall. Nonciliated columnar and cuboidal cells appear identical to their ciliated counterparts, except the cilia are absent.

Alveolar Epithelial Cells

Alveolar epithelial cells (see Figure 17-1) are cuboidal to round cells that line alveoli. They have centrally to basally located round to oval nuclei. The nuclear chromatin is slightly coarse. Cytoplasm is light blue. Occasionally the cells appear elongated, especially in FNA, due to mechanical distortion during slide preparation. Some alveolar epithelial cells are present in most pulmonary cytology specimens.

Alveolar Macrophages

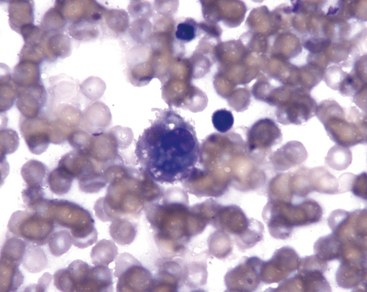

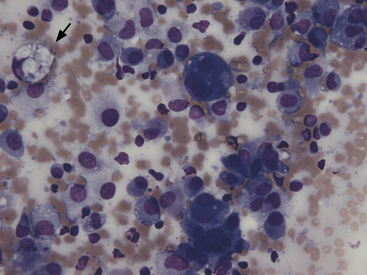

Alveolar macrophages (Figures 17-2 and 17-3) are readily found in pulmonary aspirates and impression smears from clinically normal animals. They are typically the predominant cell type. The nucleus is round to indented and eccentric. Occasional binucleate alveolar macrophages are seen in smears from clinically normal animals. Alveolar macrophages have abundant blue-gray, granular cytoplasm. Activated macrophages appear to have more abundant, vacuolated (foamy) cytoplasm and may contain phagocytized material.

Neutrophils

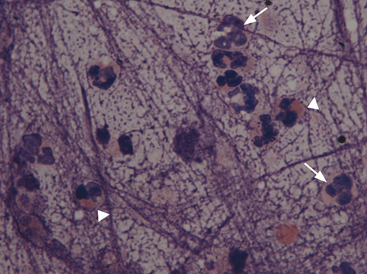

Neutrophils (Figure 17-4; see Figure 17-1) in pulmonary aspirates or impression smears look like peripheral blood neutrophils, although degenerative changes may be present. Some of the neutrophils are present because of blood contamination during aspiration or making of impression smears. The number of neutrophils present secondary to blood contamination depends on the degree of contamination and the number of neutrophils present in the peripheral blood. Generally, there is 1 white blood cell (WBC)/500 to 1000 RBCs. A relative increase in neutrophils for the amount of blood suggests inflammation, but this observation should always be compared with the peripheral leukogram to help distinguish between peripheral blood contamination and a true inflammatory cell infiltrate within the lung.

Eosinophils

Eosinophils are bone marrow–derived granulocytes containing intracytoplasmic lysosome granules. These granules have an affinity for the acid dye eosin, which stains them red or eosinophilic (see Figure 17-4). Typically eosinophils are present in very low numbers in lung specimens from clinically normal dogs and cats. Increased numbers of eosinophils indicate an allergic or hypersensitivity reaction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree