14 The lame cancer patient

The identification of an animal being lame due to a neoplastic disease usually causes owners significant distress as they face the possibility of considering amputation of the affected limb, whilst for the veterinary surgeon some careful diagnostic evaluation will be required for the case to ensure the tumour found is primary as opposed to being secondary, to ensure that there are no detectable secondary tumours present and also to consider all of the treatment options available. It is also important to remember that lameness may indicate spinal or neurological disease, so thorough clinical evaluation is essential to be sure that the clinical extent of the condition has been fully established.

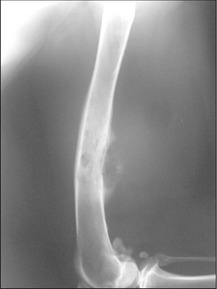

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 14.1 – OSTEOSARCOMA IN A DOg

Case history

The relevant history in this case was:

Clinical examination

Diagnostic evaluation

Treatment

Theory refresher

If the presentation of the patient is potentially consistent with a primary bone tumour, a decision has to be made whether or not to biopsy the lesion. Although in most scenarios it is vitally important to obtain a definitive diagnosis before contemplating a treatment such as amputation, if the dog, as in the case reported here, is obviously in substantial pain and the opinion of the attending clinician is that amputation may actually be the best form of analgesia the dog can receive, surgical removal of the problem with postoperative histology may be acceptable. If amputation is a treatment option that is declined by the owners, then it is essential to obtain samples for biopsy. Usually the simplest and safest way to obtain a bone biopsy sample is to use a Jamshidi needle device. These needles can be quite large but it is very important to get as much tissue as it is safely possible to do, as the histological appearance can vary within individual biopsy samples and a superficial or small biopsy may generate a misleading result. A simple closed biopsy procedure under a brief general anaesthesia is usually more than adequate, but the owners must be warned regarding the risk of pathological fracture at the biopsy site due to the pre-existing bone weakness and distortion.

Once the limb has been amputated and the dog has recovered, attention must turn to adjunctive chemotherapy. Without follow-up treatment, secondary disease often develops very rapidly (within as short a time as 3 months) and this is thought to be due to the fact that microscopic metastatic disease is likely to be present in most cases by the time they present. Many different drug regimens have been evaluated and it is clear that the platinum drugs definitely generate substantial improvements in life expectancy and outcome. Doxorubicin also shows activity against OSA but with less efficacy as a single agent when compared to the platinum drugs, so currently the authors use an alternating carboplatin/doxorubicin protocol where the drugs are given at 21-day intervals for a total of six treatments. The authors generally use carboplatin in preference to cisplatin due to its relative ease of handling, lower side effect risk and the relatively fewer health and safety concerns regarding carboplatin. This protocol has been reported to generate median survival times of 321 days with a 1-year survival rate of 48% and a 2-year survival rate of 18%. However, many other treatment combinations have been reported in which the drugs used (cisplatin, carboplatin, lobaplatin, doxorubicin), the doses used and interdose intervals are all varied and a general observation would be that most protocols generate median survival times of approximately 1 year and have 1-year survival rates of between 30 and 50%. Two-year survival rates with this approach are low.

If surgery is not a viable option for any reason, then external beam radiotherapy can help to generate some significant analgesia for OSA patients for up to approximately 3 months when given as a two-fraction treatment, usually administering up to 10 Gy per fraction. The concern regarding radiotherapy is that it may increase bone weakness at the tumour site and therefore lead to an increased risk of the dog developing a pathological fracture, especially if the analgesic action is sufficient for the dog to use the leg almost normally. Analgesia can be augmented with the NSAID meloxicam, as not only is it a highly effective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesic, it is now under investigation as an antineoplastic agent itself. In addition, the author has had some experience of using oral and injectable bisphosphonates in OSA patients. Bisphosphonates are osteoclast inhibitors and it is thought that osteoclast activity is one of the major causes of pain in bone cancer, so antagonizing these cells may help OSA patients (Figs 14.2, 14.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree