13 The haematuric/stranguric/dysuric cancer patient

Haematuria is defined as the presence of excessive numbers of erythrocytes within the urine and therefore from a cancerous disease viewpoint, haematuria can be caused by neoplasia existing potentially anywhere within the urinary tract. Stranguria usually indicates an obstruction in the lower urinary tract whilst dysuria can be suggestive of either an obstructive lesion or a neurological dysfunction. Cancer causing any of these clinical signs therefore could theoretically be located in a number of different anatomical locations and a logical step-wise approach should be taken to enable an accurate diagnosis to be made as quickly as possible.

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 13.1 – A DOG WITH A UNILATERAL RENAL CARCINOMA

Case history

The relevant history in this case was:

Clinical examination

Diagnostic evaluation

Treatment

The dog was taken to surgery for unilateral nephrectomy. Once anaesthetized the dog was placed in dorsal recumbency and the skin was routinely prepared. A ventral midline incision was made and the wound held open with a Balfour retractor. The abnormal left kidney was exposed by lifting the descending colon and moving it to the right, thereby using the mesentery attached to this to hold the small intestine towards the right hemiabdomen. The overlying peritoneum was incised and then manually peeled away from the kidney, using electrocautery to prevent any haemorrhage. The perirenal fat was then reflected to expose the renal vasculature and the ureter. The renal artery and vein were then identified and separated and then individually ligated using 3-0 silk before being transected. The ureter was then isolated and ligated close to the urinary bladder before being transected as well and the kidney removed (Fig. 13.1). The abdomen was then lavaged and closed routinely.

Theory refresher

Diagnostic imaging, and in particular ultrasound, therefore, is a very important and useful tool to help establish the diagnosis. Ultrasound-guided aspirates or Tru-cut biopsies can be obtained, although in general the authors will only request an aspirate if lymphoma is suspected. Abdominal ultrasound is also very useful to look for local and visceral metastasis and also to assess whether or not the tumour has broken through the renal capsule to invade the surrounding musculature or vasculature. Whilst local invasion of a primary renal tumour does not prevent surgical excision, it will complicate the surgery, so attempting to establish the extent of the tumour in its locality is a very important function of the ultrasound scan. Radiographs are important to establish whether or not there are pulmonary metastases present and also to look for bony metastases in a patient that may have unexplained discomfort. Renal carcinomas (in common with most carcinomas) certainly have the potential to establish bony secondaries and although not common, will cause significant bone pain which may be difficult to treat. The author (RF), however, has had some success treating bone metastasis with a combination of meloxicam and oral bisphosphonates, in terms of producing good short-term analgesia and restoring quality of life for a limited period. There has been a recent case report of a dog with a transitional cell carcinoma of one renal pelvis causing hypertrophic osteopathy and this dog presented with haematuria and a reluctance to move. Surgical excision of the tumour led to a resolution of all the clinical signs and no further limb pain.

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 13.2 – A DOMESTIC LONG-HAIRED CAT WITH RENAL LYMPHOMA

Case history

The relevant history in this case was:

Clinical examination

Diagnostic evaluation

Treatment

Theory refresher

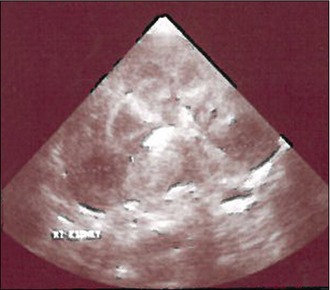

The diagnosis can usually be made using ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration but it is important to remember that this will cause some degree of renal haemorrhage, so at least an accurate platelet count should be obtained before aspiration is performed. The ultrasonographic appearance of the kidneys can be very suggestive of lymphoma and a study has suggested that there is a significant association between hypoechoiec subcapsular thickening and renal lymphoma. The positive predictive value of hypoechoeic subcapsular thickening for lymphosarcoma in the study was 80.9%, the negative predictive value was 66.7%. The sensitivity and specificity of hypoechoiec subcapsular thickening for the diagnosis of renal lymphosarcoma were 60.7% and 84.6%, respectively.

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 13.3 – TRANSITIONAL CELL CARCINOMA OF THE URINARY BLADDER

Case history

The relevant history in this case was:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree