10 The haematochezic or dyschezic cancer patient

Haematochezia describes the presence of what appears to be fresh blood on the surface of, passed concurrently with, or admixed into faeces. This is obviously different to melena, which describes dark, usually black-coloured, tarry stools caused by the presence of digested blood within the alimentary tract. Haematochezia may or may not be accompanied by dyschezia (which describes the difficult or painful passing of faeces) and/or diarrhoea, but it usually indicates disease within the colon, rectum or anus. Dyschezia commonly indicates disease within the anal or perianal tissues, so it may be possible by careful observation of the clinical signs to narrow down the location of the underlying pathology but as with any other suspected condition, a thorough clinical examination and diagnostic evaluation must always be performed to accurately locate the pathology. When considering these patients from the point of view of possible neoplastic causes, the differential diagnosis list for a patient with haematochezia and/or dyschezia is shown in Box 10.1.

Box 10.1 Differential neoplastic diagnoses for a dog or cat presenting with haematochezia or dyschezia

| Differential neoplastic diagnoses for a dog or cat presenting with haematochezia | Differential neoplastic diagnoses for a dog or cat presenting with dyschezia |

|---|---|

Extraintestinal pelvic canal neoplasia (e.g. soft-tissue sarcoma or haemangiosarcoma arising within the pelvic musculature) |

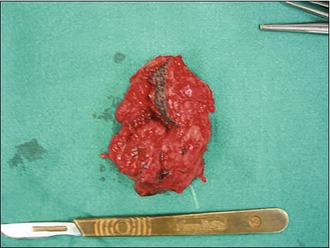

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 10.1 – A DOG WITH AN ANAL SAC ADENOCARCINOMA

Clinical history

Diagnostic evaluation

Treatment

Outcome

The dog made a rapid and excellent recovery and his signs of dyschezia resolved. The dog was monitored by clinical examination and abdominal ultrasound 3 and 6 months postsurgery but no evidence of metastatic disease was noted. Fourteen months after his surgery he developed chronic renal failure but he sadly did not respond well to treatment for this, so he was euthanized. However, abdominal ultrasound and thoracic radiographs revealed him to still be free of metastatic disease.

Theory refresher

There are many possible neoplastic differential diagnoses for a patient presenting with haematochezia or dyschezia as Box 10.1 illustrates. It is, therefore, vitally important for the attending clinician to obtain a detailed history and undertake a thorough physical examination in every case to ensure that a correct diagnosis is reached.

Apocrine gland adenocarcinomas of the anal sacs are tumours seen relatively frequently in general practice, with their incidence being quoted as 17% of all perianal tumours and 2% of all canine skin tumours (as opposed to the tumour being considered rare in cats with apocrine gland adenocarcinoma of the anal sac only being reported in two cats). Although more common in older dogs, these tumours have been reported to occur in dogs as young as 5 years old, so a careful digital evaluation of the anal sacs is highly recommended in any dog presenting with signs of dyschezia, haematochezia or in whom perianal swelling is identified. Metastatic disease can also cause pelvic obstruction presenting as obstipation.

Surgical excision is the first-line treatment for anal sac adenocarcinomas but the disease-free period and survival times may be increased if adjunctive radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy is also employed. Several studies have indicated that the median overall survival time for these patients is approximately 18 months, but the TNM staging of each tumour has significant prognostic significance (see Table 12.2). Animals with metastatic disease that cannot be treated surgically have a substantially poorer prognosis than those in whom no macroscopic disease is left behind.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree