Chapter 29 The Genus Brachyspira

The family Spirochaetaceae contains pathogens in the genera Treponema and Borrelia (see Chapter 32), and Brachyspira. Many species of Brachyspira were formerly in the genus Serpulina, which now contains only the nonpathogenic species Serpulina intermedia and Serpulina murdochii. It is apparently inevitable that both of these will move to the genus Brachyspira, leaving the genus Serpulina without legitimate members. They will be referred to here as members of the genus Brachyspira.

Brachyspira species of veterinary significance are Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, Brachyspira pilosicoli, Brachyspira aalborgi, Brachyspira intermedia, and Brachyspira alvinipulli (Table 29-1). Brachyspira innocens is a commensal. Brachyspira spp. are oxygen-tolerant anaerobes.

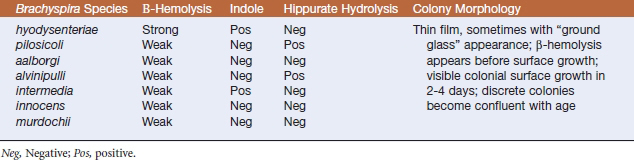

TABLE 29-1 Brachyspira Species of Veterinary Importance

| Brachyspira Species | Role in Animal Disease |

|---|---|

| B. hyodysenteriae | Swine dysentery |

| B. pilosicoli | Colonic spirochetosis in pigs, chickens, humans |

| B. aalborgi | Colonic spirochetosis in humans, nonhuman primates, opossums |

| B. alvinipulli | Colonic spirochetosis in poultry |

| B. intermedia | Colonic spirochetosis in poultry |

| B. innocens | Nonpathogen; colonizes pigs, dogs, chickens |

| B. murdochii | Nonpathogen; colonizes dogs, chickens |

BRACHYSPIRA HYODYSENTERIAE

Disease and Epidemiology

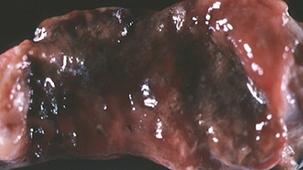

Swine dysentery is a severe mucohemorrhagic diarrheal disease characterized by extensive inflammation and epithelial necrosis of the large intestine (Figure 29-1). Pigs of any age may be affected, although disease is uncommon in neonates and is seen primarily in grower/finisher pigs. Bloody diarrhea can be fatal if not treated, or may become chronic, with dehydration and emaciation and pseudomembrane formation in the cecum, colon, and rectum. Less acute disease manifests as weight loss and mild diarrhea. Economic losses result mainly from growth retardation, medication costs, and mortality.

Pathogenesis

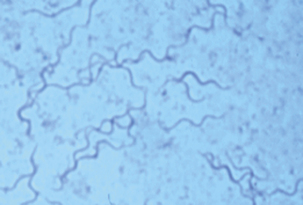

Brachyspira hyodysenteriae has two bundles of 7 to 13 periplasmic flagella, which make the organism highly motile in mucus and facilitate colonization of colonic crypts (Figure 29-2) and other mucus-covered enterocytes. Flagella are composed of three antigenically related core polypeptides and two sheath polypeptides. Flagellar mutants are avirulent in swine, suggesting that motility is an important virulence factor.

FIGURE 29-2 Brachyspira hyodysenteriae in colonic crypts (fluorescent antibody stain).

(Courtesy Lynn A. Joens.)

The pathology observed in acute cases of swine dysentery suggests involvement of one or more cytotoxins, possibly in the form of the widely observed β-hemolysin. Lesions similar to those in natural cases develop in intestinal loops exposed to purified hemolysin. Three distinct hemolysin genes, tlyA, tlyB, and tlyC, have been cloned and sequenced. Each gene is present as a single-copy chromosomal locus. Recombinant proteins are hemolytic and cytotoxic, but by an unknown mechanism; tlyA-minus mutants display decreased hemolysis in vitro and are attenuated in mice and in pigs. LPS, however, is of uncertain importance in pathogenesis, in that biological activity of LPS from B. hyodysenteriae differs little from that of B. innocens.

Diagnosis

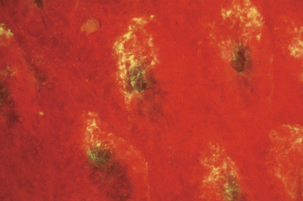

Mucosal scrapings from affected large intestine, rectal swabs, or feces should be subjected to direct examination and bacteriologic culture. Wet mounts can be examined by darkfield or phase contrast microscopy, and fixed smears should be Gram stained (using carbol fuchsin as the counterstain) and examined by brightfield microscopy. Staining with dilute carbol fuchsin, Victoria blue 4-R, or silver impregnation is also useful; the last is commonly used to demonstrate organisms in tissue. Fluorescent antibody techniques have been described. Demonstration of three to five spirochetes per high-power field is significant (Figure 29-3).

FIGURE 29-3 Brachyspira hyodysenteriae (Victoria blue 4R-stained smear from colon).

(Courtesy D.L. Harris.)

Brachyspira hyodysenteriae (and other members of the genus) grow slowly and are nutritionally fastidious. Specimens are plated onto selective blood agar (containing colistin, vancomycin, and spectinomycin, or spectinomycin alone). Plates incubated at 42° C in an anaerobic environment containing hydrogen and carbon dioxide are examined at 48-hour intervals for up to 10 days. Key features in identification of B. hyodysenteriae are colonial morphology, degree of β-hemolysis, production of indole, and hippurate hydrolysis. Brachyspira hyodysenteriae produces small, translucent colonies with a zone of clear hemolysis after approximately 48 hours’ incubation. Incorporation of 1% sodium RNA into media enhances growth, but also accentuates the difference in hemolysis between B. hyodysenteriae and B. innocens, the latter being weakly β-hemolytic. Brachyspira hyodysenteriae is indole positive and hippurate negative (Table 29-2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree