Chapter 7 The Genus Bacillus

Bacilli are strictly aerobic or facultatively anaerobic, spore-forming rods (Figure 7-1). Most are catalase positive and motile, many are gram variable, and all are mediumto large. Spores may be readily visualized or may require induction by incubation at 42° C or for an extended period at 37° C.

FIGURE 7-1 Bacillus anthracis gram-stained smear from pure culture.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #1064, William A. Clark, Atlanta, date unknown, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Diseases and Epidemiolgoy

Egyptian and Mesopotamian writings from approximately 5000 BC describe a cattle disease that very much resembles anthrax, and may have been the cause of two of the plagues on the Egyptians and their cattle, described in Exodus 9 (the “murrain of beasts…” and the “plague of boils and blains…”). In his treatise on agriculture, Virgil describes a disease of domestic animals and man that is almost certainly anthrax.

Human Anthrax

Cutaneous anthrax (Figure 7-2) follows entry of the organism into a cut or abrasion. The incubation period is usually 24 to 72 hours, but can range up to 2 weeks. Signs begin with a painless papule, which becomes vesicular in 1 to 2 days, and can be surrounded by an extensive area of edema. The vesicle ulcerates by day 5 or 6 and the lesion dries, leaving a blackened necrotic area, the so-called black eschar. Affected individuals may also experience fever, malaise, headache, and swelling of draining lymph nodes. About 20% of untreated cases will progress to fatal septicemia. The case fatality rate with timely antimicrobial therapy is less than 1%, although treatment does not stop the progression of lesions.

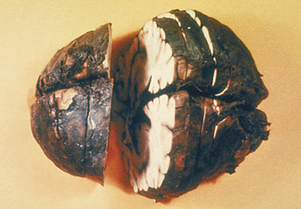

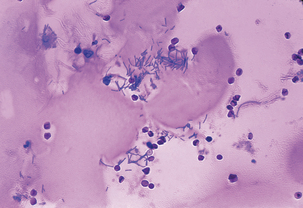

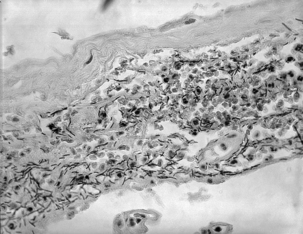

As spores germinate in macrophages and are carried to mediastinal lymph nodes, the patient may experience sore throat, mild fever, and muscle aches, which progress rapidly to severe respiratory difficulty. Organisms originating in the lungs and, later, those in the bloodstream, are temporarily removed by the reticuloendothelial system; however, B. anthracis ultimately escapes the lymphatics to produce overwhelming septicemia, usually with meningitis (Figures 7-3 through 7-5). Sudden onset of acute symptoms, including hypotension, edema, and fatal shock follow in2 to 5 days. Estimates of the case-fatality rate arebased upon limited data, but are probably at least90% and, without therapy, are more nearly 100%. Therapeutic intervention is of little use unlessinitiated quite early in the clinical course.

FIGURE 7-3 Meningitis in human systemic Bacillus anthracis infection.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #1121, Atlanta, 1966, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

FIGURE 7-4 Bacillus anthracis in cerebrospinal fluid of patient with meningitis.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #1782, Marshal Fox, Atlanta, 1976, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

FIGURE 7-5 Meningeal tissue, showing large numbers of Bacillus anthracis.

(Courtesy Public Health Image Library, PHIL #1791, Dr. LaForce, Atlanta, 1967, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

In the United States, as many as 130 cases of human anthrax occurred each year at the beginning of the twentieth century, but this declined to zero annual incidence through most of the 1990s. Most infections have been cutaneous, although 18 were pulmonary, the last in 1976 in a weaver. Worldwide, human anthrax is particularly common in agricultural regions with inadequate programs for control of livestock anthrax; in South and Central America, southern and eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and the Middle East, where animal anthrax occurs frequently, human cases are common and more than 95% are cutaneous. A recent epidemic in Zimbabwe comprised nearly 10,000 cases, with a case fatality rate of less than 2%.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree