Chapter 22 The Genus Actinobacillus

Disease associated with members of the genus Actinobacillus(family Pasteurellaceae) was first reported in 1902, in the form of bovine subcutaneous abscesses from which gram-negative rods were consistently recovered. The overwhelming majority of the species or specieslike taxa included in the genus are commensals, or pathogens, of animals (Table 22-1).

TABLE 22-1 Relationship Between Species of Actinobacillus and Preferred Host

| Species | Disease(s) | Host(s) |

|---|---|---|

| A. actinomycetemcomitans | Periodontitis | Man |

| A. arthritidis | Arthritis, septicemia | Horse |

| A. capsulatus | Arthritis, septicemia | Rabbit |

| A. delphinicola | Uncertain significance | Sea mammals |

| A. equuli ssp. equuli | “Joint ill,” septicemia abortion, metritis, septicemia | Horse |

| A. equuli ssp. haemolyticus | Various disease conditions | Horse |

| A. genomospecies 1 | Stomatitis | Horse |

| A. genomospecies 2 | Septicemia | Horse |

| A. hominis | Respiratory disease | Man |

| A. indolicus | Uncertain significance | Pig |

| A. lignieresii | Pyogranulomatous lesions (“wooden tongue”) | Ruminants |

| A. minor | Uncertain significance | Pig |

| A. muris | Uncertain significance | Rodents |

| A. pleuropneumoniae | Fibrinous pleuropneumonia | Pig |

| A. porcinus | Uncertain pathogenic significance | Pig |

| A. rossii | Abortion, metritis | Pig |

| A. scotia | Uncertain significance | Sea mammals |

| A. seminis | Epididymitis, orchitis | Sheep |

| A. succinogenes | Uncertain significance | Cattle |

| A. suis | Septicemia | Pig |

| A. ureae | Respiratory disease | Man |

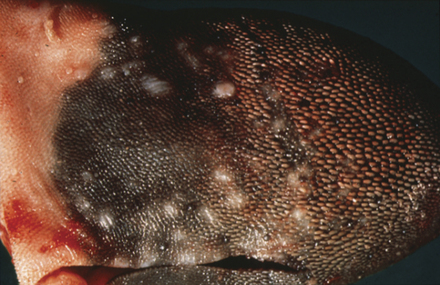

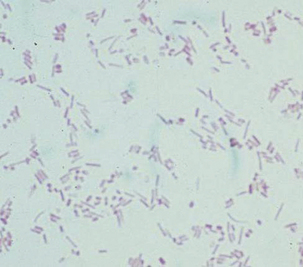

Actinobacilli are gram negative and pleomorphic, with mostly bacillary and occasional coccal elements with a “Morse code” appearance (dots and dashes) on Gram stain (Figure 22-1). Organisms are variably hemolytic on blood agar, nonmotile, usually oxidase positive, catalase variable, and nitrate-reductase positive. They are facultatively anaerobic, but added CO2 is required for growth. Carbohydrates are fermented without the production of gas. Most species grow on triple-sugar iron agar slants, yielding a typical orange cast to the medium, and most grow on MacConkey agar as tiny lactose-fermenting colonies. Colonies may be very sticky or waxy, especially on primary culture plates.

FIGURE 22-1 Typical Gram stain of Actinobacillus sp., denoting “Morse code” appearance.

(Courtesy J. Glenn Songer.)

DISEASES AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

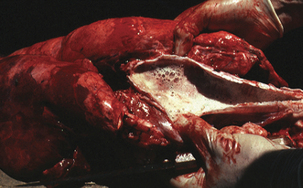

Actinobacillus lignieresii is a commensal of the ruminant oropharynx and is recovered from rumen contents. Actinobacillosis or “wooden tongue” in ruminants results in the formation of hard tumorous masses in the tongue (Figure 22-2). Affected animals suffer from dysphagia, with resulting weight loss. Soft tissue infections primarily of the head and neck have been described in cattle and sheep; these lesions contain odorless pus. The disease is often confused with actinomycosis, but true actinomycosis is found in bone, whereas actinobacillosis affects soft tissues. Actinobacillus lignieresii has, on occasion, been isolated from pneumonic sheep lungs, tongue lesions of dogs, swollen lymph nodes of rats, and mastitic bovine mammary glands. Young animals appear to be more susceptible to infection, based on experimental inoculation studies. Trauma is an important predisposing factor because the organism gains entrance into the underlying soft tissues through penetration of the mucosal or epithelial barriers. Infections are most often sporadic, but consumption of dry, stemmy haylage has been associated with “outbreaks” of wooden tongue in cattle.

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae colonizes the tonsils and upper respiratory tract of apparently healthy pigs, where it is considered an obligate parasite. No other natural hosts have been described. Transmission is through direct contact or aerosol exposure to infected pigs. The organism is the causative agent of porcine pleuropneumonia, a highly infectious disease that causes sizable economic losses to the swine industry and has worldwide distribution. At present, 15 different serotypes and 2 biotypes have been described. The presence and prevalence of serotypes vary among countries, with serotypes 1, 5, and 7 most commonly isolated in North America, and serotypes 2 and 9 predominant in Europe. All serotypes are capable of producing disease, but they are of varying virulence. Outbreaks are usually associated with intensive pig production in which there is high-stocking density, poor ventilation, and low immunity. Animals younger than 6 months are most frequently affected. They experience a wide spectrum of signs, ranging from sudden death to chronic pneumonia, depending on the serotype of the infecting strain, the infectious dose, and the immune status of the host. Acute disease is characterized by a hemorrhagic necrotizing pneumonia of the caudodorsal aspect of the caudal lung lobe and fibrinous pleuritis with high morbidity and mortality (Figure 22-3). Coughing and expiratory dyspnea (“thumping”) are common. Pregnant sows may abort. Hemorrhagic froth may be discharged from the nose or mouth immediately before death. Morbidity and mortality rates range from 30% to 50%. Concurrent infection with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRS) and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae may exacerbate the illness. Acute disease becomes less common as herd immunity increases. Survivors grow poorly because of inhibition of normal respiratory function resulting from lung scarring with pleural adhesions. These chronically infected animals continue to harbor A. pleuropneumoniae in their tonsillar crypts and are the main means of transmission between herds.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree