Chapter 24 The Genera Haemophilus, Histophilus, and Taylorella

THE GENUS HAEMOPHILUS

Haemophilus spp. are assigned to the family Pasteurellaceae and are common commensal organisms of the mucous membranes of animals and humans. They are highly susceptible to desiccation and, in consequence, cannot survive for long periods in the environment. Most species are opportunists in stressed or compromised hosts, but some, such as Haemophilus parasuis in swine, cause more serious disease. Most animals and birds harbor at least one species-specific strain (Table 24-1). Human disease caused by species other than Haemophilus influenzae has, with some exceptions, been considered unusual.

TABLE 24-1 Haemophilus Species of Veterinary Significance

| Organism | Host(s) | Disease condition(s) |

|---|---|---|

| H. felis | Cat | Rhinitis, conjunctivitis |

| H. influenzaemurium | Rodents | Respiratory, ocular disease |

| H. haemoglobinophilus | Dog | Normal preputial flora; rare vaginitis, cystitis, balanoposthitis |

| H. paracuniculus | Rabbit | From animals with mucoid enteritis; virulence unknown |

| H. paragallinarum | Chicken | Infectious coryza |

| H. parasuis | Pig | Glässer’s disease, meningitis, myositis, pneumonia, septicemia |

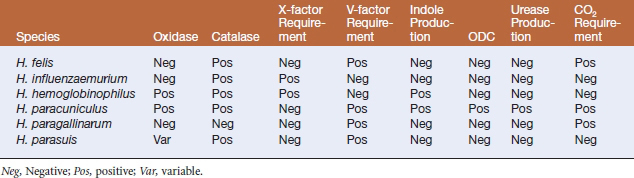

All members of the genus Haemophilus are small, pleomorphic, facultatively anaerobic, nonmotile, gram-negative rods to coccobacilli that may form filaments during periods of environmental stress. The genus name is in reference to the fact that these organisms require factors X (hemin) and/or V (NAD) in blood for growth. Species designated with the prefix “para” require only V factor. Optimal growth is obtained in an atmosphere of 5% to 10% CO2. The most uniformly satisfactory medium for propagation of Haemophilus species is chocolate agar because it provides both X and V factors. On blood agar, Haemophilus colonies cluster around a Staphylococcus streak line in a phenomenon called satellitism. Phenotypic characteristics allow differentiation of Haemophilus spp. (Table 24-2).

HAEMOPHILUS PARAGALLINARUM

Haemophilus paragallinarum is the agent of infectious coryza, an upper respiratory disease of laying and growing chickens worldwide. Disease is exacerbated by concurrent mycoplasmal or viral infections and, in those situations, mortality may be high. A characteristic swelling of the infraorbital region, oculonasal discharge, swollen wattles, diarrhea, and inappetence are common clinical signs (Figure 24-1). Losses result from decreased feed consumption, which impacts egg and meat yield. Unusual clinical presentations in developing countries include arthritis and septicemia. Lesions observed at necropsy are associated with catarrhal inflammation of the respiratory tract, and include sinusitis with congestion, edema, and sloughing. Disease transmission is via the respiratory route or through contact with contaminated drinking water. Susceptible birds exposed to the agent usually develop clinical signs within 3 days. Birds that recover from acute illness may be a source of infection for young chicks that become susceptible 4 weeks after hatching. Serogroups A, B, and C of H. paragallinarum are currently recognized, with four serovars in groups A and C. Infectious coryza has been infrequently diagnosed in pheasants, guinea fowl, quail, and companion birds. Ducks, turkeys, and pigeons are refractory to experimental infection.

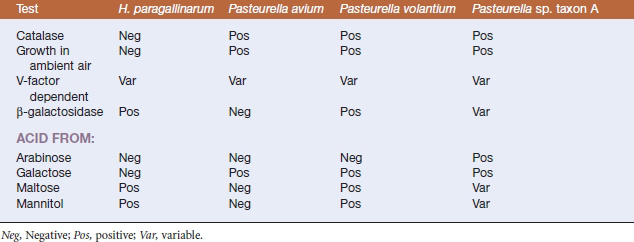

Diagnosis of infectious coryza is based on the characteristic clinical signs (facial swelling), recovery of the bacterium from clinical materials, and results of serologic testing. Although fastidious, H. paragallinarum is easily recovered from the sinuses of affected birds in the acute stage of infection, by bacteriologic culture on chocolate agar. The strain characterized originally apparently required both X and V factors, but the current representatives of H. paragallinarum require only V factor, and V-factor independent strains have been recovered from chickens in South Africa. Differentiation of the pathogenic H. paragallinarum from Haemophilus-like commensals of the avian upper respiratory tract can be based on phenotypic differences (Table 24-3). Several serologic assays allow detection of antibodies to H. paragallinarum, and the test of choice appears to be hemagglutination inhibition, which detects both vaccinal titers and those resulting from infection. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test allows rapid diagnosis of coryza but has limited availability.

TABLE 24-3 Characteristics Useful in the Differentiation of Haemophilus paragallinarum from Avian Haemophilus-like Organisms

HAEMOPHILUS PARASUIS

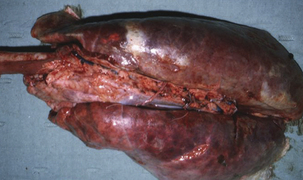

Haemophilus parasuis is a primary agent in nursery mortality. Disease severity, as well as the age of the affected animals, depends on the health status of the herd and the virulence of the infecting strain. In some herds, disease can occur within a week of weaning, and this reflects a deficiency in maternal immunity. Animals are affected at 4 to 6 weeks postweaning in the majority of herds. Glässer’s disease is characterized by a high fever (107° C), swollen joints, respiratory distress, and central nervous system (CNS) signs. Severe lesions observed at necropsy include fibrinous exudates in the pleura, pericardium, synovia, meninges, brain, and peritoneal cavity (Figures 24-2 and 24-3). Acute pneumonia without polyserositis has been reported in older animals in endemically infected, stable herds. Acute septicemia or arthritis may occur in adult populations, especially sow herds. Other disease manifestations include acute fasciitis and myositis in primary SPF sows, in the absence of lesions of septicemia, pneumonia, or polyserositis.

FIGURE 24-2 Respiratory lesions of Glässer’s disease in a finishing pig.

(Courtesy Raymond E. Reed.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree