Chapter 41 The Genera Chlamydia and Chlamydophila

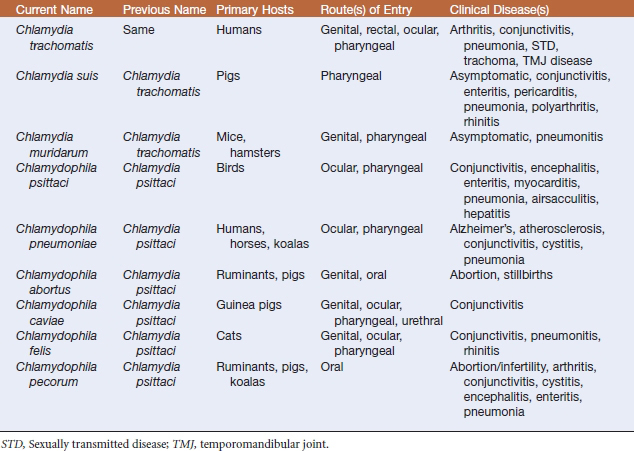

Members of the order Chlamydiales are gram-negative obligate intracellular bacterial pathogens that parasitize hosts from humans to amebae. The family Chlamydiaceae has recently undergone extensive taxonomic revision, and the two proposed genera are Chlamydia and Chlamydophila. The genus Chlamydia would include Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia suis, and Chlamydia muridarum. Six species assigned to the genus Chlamydophila are Chlamydophila abortus, Chlamydophila caviae, Chlamydophila felis, Chlamydophila pecorum, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Chlamydophila psittaci. This newly proposed nomenclature is not yet widely accepted.

The order Chlamydiales has a developmental cycle (Figure 41-1) that is unique among prokaryotes, with two morphologically distinctive forms. The elementary body is the smaller (300-400 nm), infectious form, whereas the reticulate body is larger (800-1000 nm) and noninfectious. Elementary bodies are similar to spores, in that they are designed for survival in the environment. The reticulate body is metabolically active and capable of replication.

DISEASES AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

The Chlamydiaceae are pathogens of mammals, birds, and reptiles, and most have specific host or disease associations (Table 41-1). The host may serve as a natural reservoir of infection because many chlamydiae inhabit hosts in an asymptomatic state. Chlamydiae are spread by direct contact or through aerosols and do not require an alternate vector.

Chlamydia trachomatis is a human pathogen. Various strains are etiologic agents of prevalent sexually transmitted diseases and are the main causes of preventable blindness (trachoma) worldwide. Cervical infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility may affect women. Infants, infected in the birth canal, may develop pneumonia or conjunctivitis. In most cases, the conjunctivitis is self-limiting, but in some instances it results in blindness. In males, urethritis and lymphogranuloma venereum predominate. The latter condition is characterized by swollen lymph nodes in the groin. A secondary consequence of infection, more common in men than in women, is arthritis or Reiter’s syndrome. This organism has also been found in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) of patients with TMJ disorder.

Chlamydophila psittaci isolates associated with abortion in sheep, goats, cattle, and swine are now called C. abortus. These strains are endemic among ruminants and are colonizers of the placenta. Enzootic ovine abortion is the most common disease attributed to this organism, and is reported in the United States, South Africa, and Europe. The disease is characterized almost exclusively by a loss of lambs in late pregnancy, although weak or dead lambs may be born at term. Retained placenta and vaginal discharge are common clinical signs. Chlamydiae are present in high numbers in fetal membranes and in vaginal discharge; under these conditions, disease is spread to other ewes by the oral route. Bacteria can persist in ewe lambs for up to 2 years before causing abortion. The organism may have a broader than believed host range in that it has apparently been recovered from abortions in horses, rabbits, guinea pigs, and mice. Pregnant women working with infected sheep are at increased risk of abortion.