CHAPTER 18 The Gastrointestinal Tract

TECHNIQUES TO OBTAIN CYTOLOGIC SPECIMENS FROM THE ALIMENTARY TRACT

Fine-needle aspirates (FNAs), endoscopic brushings, and biopsy imprints are used to obtain samples for most of the GI tract. All techniques have their advantages and disadvantages and these are summarized in Table 18-1. Descriptions of aspiration techniques, smear and imprint preparation, and staining are detailed in Chapter 1.

Table 18-1 Advantages and Disadvantages Associated with Techniques for Obtaining Cytologic Specimens from the Alimentary Tract

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Fine-needle aspirates | Quick and easy Economical Noninvasive Minimal equipment (no anesthesia, +/- ultrasound guidance) | Largely restricted to mass lesions |

| Endoscopic brushings | Direct visualization of mucosal lesions Good sampling of epithelium | Samples only epithelium Samples only where endoscope can reach Requires sedation or anesthesia Moderately expensive |

| Impression smears – endoscopic biopsy | Direct visualization of mucosal lesions Less invasive than full-thickness biopsies | Samples only mucosa +/- superficial submucosa Samples only where the endoscope can reach Limited sampling of lesion Requires sedation or anesthesia Moderately expensive |

| Impression Smears – full-thickness surgical biopsy | All layers of intestinal wall can be examined Generally better sample quality than endoscopic biopsies | Most invasive method Requires general anesthesia Expensive |

Fine-Needle Aspiration

Aspiration of the GI tract generally requires ultrasound guidance. FNAs are often used to sample masses, especially those that involve the submucosa and muscular wall that more superficial sampling techniques cannot reach. When obtaining FNAs, care should be taken to prevent or minimize contamination of the cytologic specimens with ultrasound gel because the gel stains intensely and can obscure cytologic details (Figure 18-1).

Endoscopic Brushings

Mucosal brushings can be obtained during endoscopy procedures. The technique involves passing a cytology brush through the endoscope and rubbing it on the desired area until slight bleeding is observed. The brush with its sample is then withdrawn from the endoscope and rolled onto a glass slide. Endoscopic brushings are an excellent technique to collect mucosal samples but they are limited by the length that can be reached and they can sample only the epithelial surface.1

Rectal Scrapings

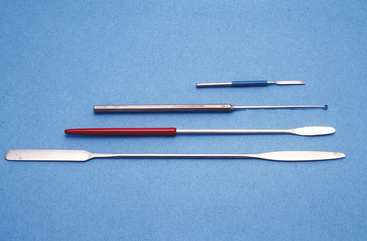

Although most of the GI tract is difficult to reach for cytologic examination, the rectum is easily accessible for sampling. Mucosal scrapings are an easy, noninvasive method to obtain cytologic samples when large intestinal disease is suspected (Box 18-1). The object of a rectal mucosal scraping is to remove the overlying epithelium and obtain a sample from the lamina propria. Microscopic examination of this sample may reveal inflammation, infectious agents, or an infiltrating neoplasm. A rectal mucosal scraping is performed with a rigid instrument, such as a chemistry spatula, conjunctival scraper, or ear curette (Figure 18-2). Cotton swabs usually do not produce diagnostic samples because they are not abrasive enough to get a subepithelial sample. The rectum is first cleaned of feces so that a sample of mucosa, rather than adherent feces, is obtained. The instrument is guided into the rectum with a gloved finger as for performing a digital rectal examination. Lubricant is avoided or used sparingly because it stains intensely with Romanowsky stains and can obscure cytologic structures. The instrument must be inserted far enough craniad to avoid the anus and reach the rectum. The instrument is drawn along the mucosa several times in a firm stroking motion. Scraping must be firm enough to remove the epithelium and collect material in the lamina propria but not so vigorous as to perforate the rectum. Perforation is especially a consideration in animals with chronic ulcerative colitis, in which the colon may be very friable. The scraper is removed from the rectum with the finger protecting the surface of the instrument so that the sample is not lost. The material is then placed on a glass slide and smeared with the scraping instrument or gently pressed with a second slide to make a smear consisting of a single layer of cells.

CYTOLOGIC EVALUATION OF THE ALIMENTARY TRACT

Esophagus

Neoplasia

Esophageal neoplasia accounts for less than 5% of all alimentary neoplasia. Squamous cell carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, fibrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma have been reported in dogs and cats. There is a causal association between infection with the parasite Spirocerca lupi and development of esophageal sarcomas in dogs.2,3

Stomach

Normal Cytology

A normal gastric cytology specimen predominantly contains superficial mucus-secreting columnar epithelial cells. These cells will often be found in monomorphic honeycomb sheets or small strips of columnar cells (Figure 18-3). Individual cells contain a single, basally situated nucleus and finely granular cytoplasm. Chief and parietal cells will occasionally be seen. Chief cells can be recognized by their polygonal shape and numerous basophilic zymogen granules (Figure 18-4). Parietal cells are pyramidal and contain granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm.4 FNAs or impression smears of deeper layers may also contain a few spindle-shaped smooth muscle cells or fibroblasts. These cells have an elongated nucleus with a dense chromatin pattern and attenuated, light blue cytoplasm. Various pieces of digesta and oral contaminants (mixed bacteria, including Simonsiella spp. and squamous cells) can sometimes be found along with an occasional neutrophil. Increased numbers of neutrophils may be associated with areas of ulceration.

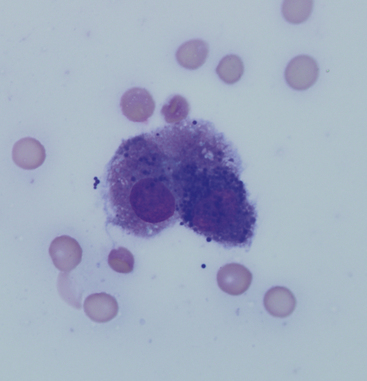

Figure 18-4 A gastric chief cell. This cell contains numerous basophilic zymogen granules. (Modified Wright’s stain.)

Inflammation and Infection

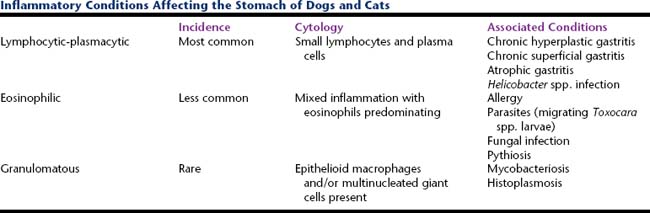

Inflammatory conditions affecting the stomach may be the result of reactions to food antigens, microbial organisms, or self-antigens (Table 18-2).

Lymphocytic-Plasmacytic Gastritis

This is the most common form of gastric inflammation and is characterized cytologically by a moderate number of mature lymphocytes and plasma cells scattered amongst well-differentiated gastric epithelium.5 Chronic hyperplastic gastritis, chronic superficial gastritis, atrophic gastritis, and Helicobacter infection are commonly associated with lymphocytic-plasmacytic inflammation.5

Eosinophilic Gastritis

Eosinophilic gastritis is less common and can be diagnosed by observing a mixed inflammatory population that is predominantly eosinophilic. Focal eosinophilic inflammation is found in association with migrating Toxocara canis larvae in dogs. Diffuse eosinophilic gastritis is thought to be allergic in nature but often the underlying cause is never found. It may be limited to the stomach or it may be part of a larger eosinophilic gastroenterocolitis complex. In cats, eosinophilic gastritis may also be part of the hypereosinophilic syndrome.5 T-cell lymphoma, mast cell tumor, and pythiosis also may be associated with eosinophilic infiltration. Tumor cells will predominate over the eosinophils in cases of lymphoma and mast cell tumor, whereas pythiosis-related inflammation will also contain macrophages and other inflammatory cells.

Granulomatous Gastritis

Granulomatous gastritis is characterized by the presence of epithelioid macrophages and multinucleated giant cells and is rare in dogs and cats. This uncommon inflammatory infiltrate has been associated with mycobacteriosis and histoplasmosis.5 Mycobacterium spp. are small, refractile, bacilli that do not stain with Romanowsky stains but may be visible as negative images against other material that does stain. Acid-fast stain can be applied to demonstrate the Mycobacterium spp. Histoplasma capsulatum organisms are described under “Rectal Scrapings.”

Helicobacter

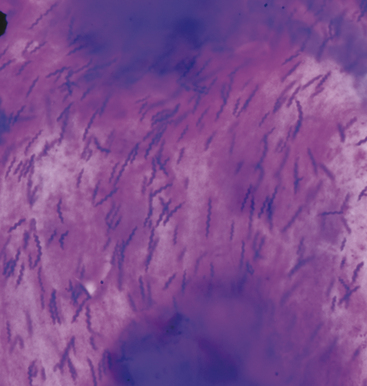

Helicobacter organisms are sometimes observed and their association, if any, with gastric disease is still debatable.6 Cytologically, these bacteria have a typical corkscrew appearance (Figure 18-5). Organisms are more commonly seen, and in larger numbers, with cytologic as opposed to histologic specimens. The reason for this discrepancy is that Helicobacter spp. are associated with the luminal mucous layer. This layer is readily sampled with cytologic techniques but will often be lost by fluid agitation during formalin fixation and routine tissue processing for histologic examination.7 Helicobacter bacteria are spiral-shaped, gram-negative rods that measure approximately 3.0 × 0.5 μm. Spiral-shaped bacteria can be present in cytologic specimens from healthy animals, but many more organisms usually are associated with gastritis. In addition, inflammation is present with gastritis.8,9

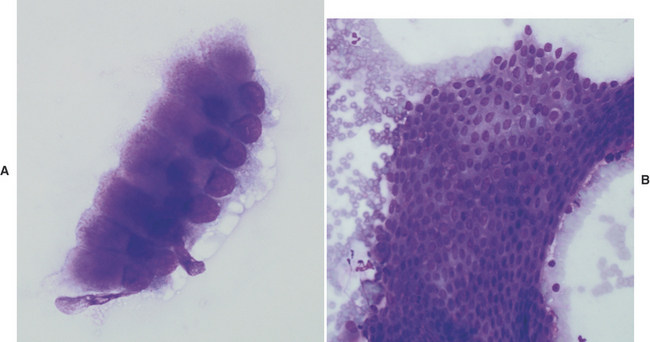

Pythiosis

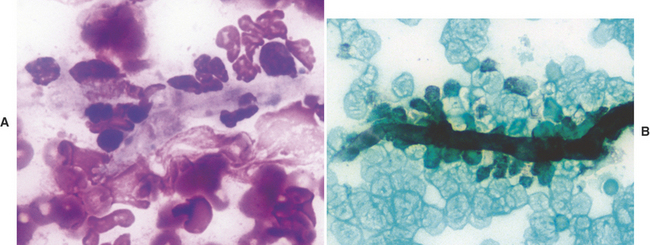

Gastric pythiosis is infrequently diagnosed in dogs. The gastric wall is usually thickened by a proliferative inflammatory response that resembles a tumor-like mass. Aspiration of these lesions will obtain many eosinophils admixed with fewer neutrophils and macrophages. Hyphae of Pythium insidiosum stain poorly, if at all, with Romanowsky stains, but may appear as clear elongate structures surrounded by inflammatory cells (Figure 18-6, A). If necessary, Gomori’s methenamine silver (GMS) stain may be applied to demonstrate the hyphae, which stain black (Figure 18-6, B).

Neoplasia

Gastric neoplasia accounts for <1% of all neoplasia in the dog and cat.3,10 Malignant neoplasms predominate in dogs, with adenocarcinoma being most common followed by lymphosarcoma and leiomyosarcoma. Benign neoplasms are rare and include adenomas and leiomyomas.11 Adenomas, often found in the pyloric region, cannot be differentiated from epithelial hyperplasia based on cytology alone because both lesions will exfoliate moderate numbers of normal-appearing epithelial cells. Lymphosarcoma is the most common gastric tumor in the cat; adenocarcinoma is rare.11

Gastric Adenocarcinoma

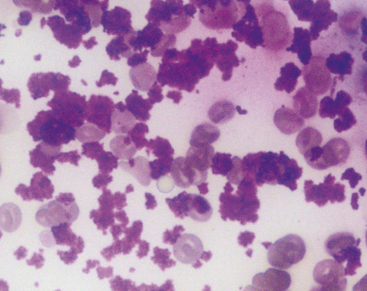

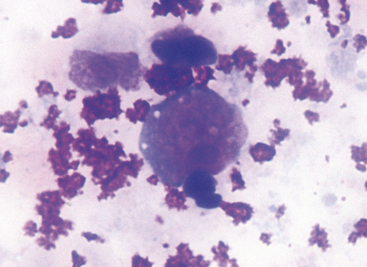

Adenocarcinomas typically occur in older dogs and cats and can present as a sessile polyp, ulcerated plaque, or diffuse thickening of the gastric wall.10 These tumors may develop on the mucosal surface of the stomach or they may grow into the deeper layers. Consequently, brushings or impression smears of the mucosal surface may not always obtain a diagnostic sample. Neoplastic cells often have a lymphoid appearance (Figure 18-7). Individual cells are large and round and have a round nucleus, fine chromatin pattern, and one or two prominent nucleoli. A thin rim of dark blue and granular cytoplasm is present. In some tumors that elicit a connective tissue response (desmoplasia), scattered fibroblasts also may be present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree