Chapter 43 The Family Rickettsiaceae

Rickettsioses are some of the oldest diseases known to man. On one hand, epidemic typhus was responsible for large outbreaks of plaguelike illness in ancient Greece. On the other hand, rickettsioses comprise some of the most recently recognized emerging infectious diseases.

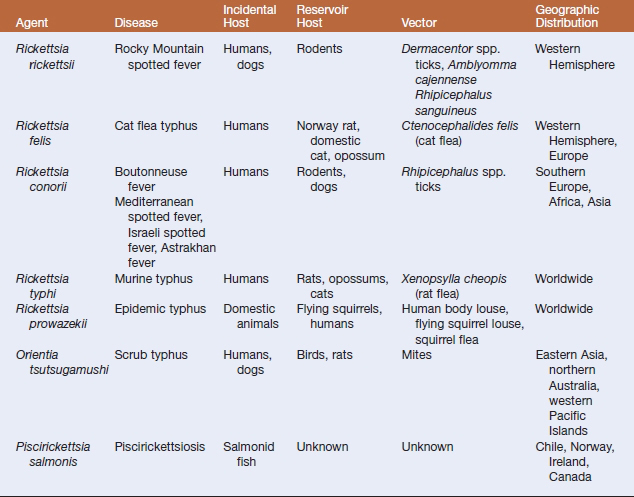

Bacteria classified in the family Rickettsiaceae have recently undergone extensive taxonomic revision. Initial phylogenetic and taxonomic studies were based on morphologic, antigenic, and metabolic characters. Analysis of data from 16S rRNA gene sequence studies has resulted in amendment of the description of the family Rickettsiaceae to include organisms that are obliged to reside in host-cell cytoplasm or nucleus and are not bound by vacuoles. As a result, the genera Ehrlichia, Cowdria, Neorickettsia, Coxiella, and Wolbachia have been removed from the family. Three genera now included are Rickettsia, Orientia, and Piscirickettsia (Table 43-1).

THE GENUS RICKETTSIA

Rickettsia rickettsii

Rickettsia rickettsii is pathogenic for humans and other animals, and causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) in the former. RMSF was first recognized in 1896 in humans residing in the Snake River Valley of Idaho, where it was originally known as “black measles” because of its characteristic rash. It was a dreaded and frequently fatal disease that affected hundreds of people in the region. The geographic distribution of RMSF has grown to encompass most of the continental United States, as well as portions of southern Canada, Central America, Mexico, and South America. Thus RMSF has become a misnomer.

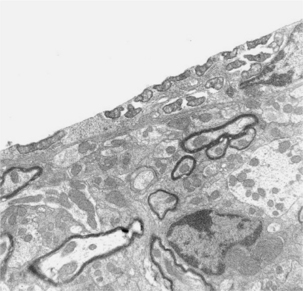

Rickettsia rickettsii is a very small gram-negative intracellular bacterium that ranges in size from 0.2 × 0.5 µm to 0.3 × 2 µm. These organisms are difficult to see in tissues stained by routine methods, and generally require the use of special staining methods (i.e., immunohistochemical or fluorescent antibody). The bacteria are present in the cytoplasm of infected cells (Figure 43-1).

DISEASE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

RMSF, like all other rickettsial infections, is a zoonosis. Many of these diseases require a vector (e.g., a mosquito, tick, or mite) in order to be transmitted from the animal to human. Ticks are the natural hosts of RMSF, serving as both reservoirs and vectors of R. rickettsii. Transmission is primarily by bites, but may occur following exposure to crushed tick tissues, fluids, or feces. Only members of the tick family Ixodidae (hard ticks) are naturally infected with R. rickettsii. These ticks have four stages in their life cycle (egg, larva, nymph, and adult), across which transmission can occur. Transovarial transmission also occurs. Larval or nymphal ticks can become infected during feeding. Furthermore, male ticks may transfer R. rickettsii to female ticks through body fluids or spermatozoa during the mating process. The infected tick can maintain the pathogen for life.

The two major vectors of R. rickettsii in the United States are the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) and the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni) (Figure 43-2). The former is widely distributed east of the Rocky Mountains and also occurs in limited areas on the Pacific Coast. Dogs and medium-sized mammals are the preferred hosts of adult D. variabilis, although it feeds readily on other large mammals, including humans. It is the species most often responsible for transmitting R. rickettsii to humans and dogs. Dogs are sensitive indicators of the presence of disease, and they represent important transport hosts because they bring ticks into contact with humans.

More than half of RMSF cases occur in the south Atlantic region of the United States (Delaware, Maryland, Washington, D.C., Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida). Infection also occurs elsewhere in the country, including the Pacific Coast (Washington, Oregon, and California) and western south-central (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas) regions. The highest incidence of RMSF is in North Carolina and Oklahoma, which, combined, accounted for 35% of all cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from 1993 through 1996.