Chapter 45 The Cutaneous Mycoses

The cutaneous mycoses of animals include a wide variety of diseases of the integumentary system and its appendages. Although fungal infection is usually restricted to these areas, pathologic changes may occur elsewhere in the animal because of the presence of the agent and its metabolites. The great majority of these mycoses are caused by the dermatophytes (“skin plants”), or so-called ringworm fungi. In the strictestsense, dermatophytosis is an infection caused by a dermatophyte in the keratinized tissues, which include hair, feathers, stratum corneum layers of the skin, and, to a lesser degree, the nails, claws, and horns. Yeasts and normally saprophytic filamentous fungi cause cutaneous infections resembling dermatophytoses, and these are collectively referred to as the dermatomycoses.

Dermatophytes are generally grouped into three categories based on their host preference and natural habitat (Table 45-1). Zoophilic organisms are pathogens of animals or birds, but may infect humans through contact with infected animals. Geophilic species are soil-associated organisms, whereas anthropophilic species are near-exclusive pathogens of humans, rarely infecting animals.

TABLE 45-1 Classification of Dermatophytes Isolated from Domestic Animals Based on Host Preference and Natural Habitat

| Anthropophilic | Geophilic | Zoophilic |

|---|---|---|

| Epidermophyton floccosum | Microsporum gypseum | Microsporum canis |

| Trichophyton rubrum | M. nanum | M. equinum |

| T. schoenleinii | M. persicolor | M. gallinae |

| T. tonsurans | M. vanbreuseghemii | Trichophyton mentagrophytes |

| T. violaceum | M. cookei | T. simii |

| Microsporum audouinii | T. verrucosum | |

| M. megninii |

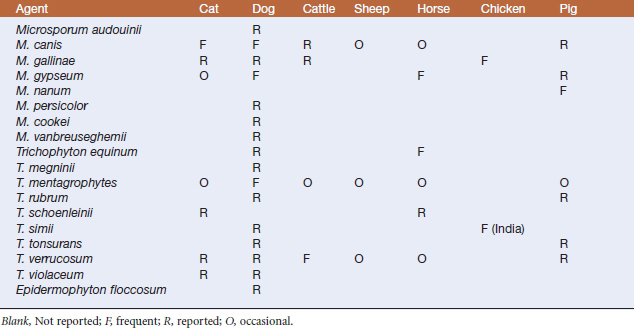

The common etiologic agents of the animal dermatophytoses are classified into the anamorphic (asexual or imperfect state) genera Microsporum and Trichophyton. When members of these genera reproduce sexually, by producing ascomata with asci and ascospores, they are classified in the teleomorphic (sexual or perfect state) genus Arthroderma, in the family Arthrodermataceae, within the order Onygenales, and phylum Ascomycota. A third dermatophytic genus, Epidermophyton, is anthropophilic, although it has been isolated on occasion from dogs. Dermatophytes isolated from domestic animals are listed in Table 45-2.

Animal dermatomycoses include nondermatophytic superficial and cutaneous fungal infections with organisms such as Malassezia spp. and Trichosporon spp. These are quite common and often result from an alteration of skin flora or immune status in the host.

DISEASES AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Zoophilic dermatophytes are parasites of the skin of animals and not known to live in the soil; soil survival is possible, especially if embeddedin hair, feathers, or skin scales. This is especially common in catteries, where recurrent ringworm infections may be common. Zoophilic dermatophyte infections are most often observed in young animals that are kept in proximity to one another. Predisposing factors include hot, humid conditions; trauma; and poor nutrition. Conidialsurvival in the environment depends directly on moisture. Although extremely resistant to freezing, spores tend to be susceptible to desiccation and high environmental temperatures. Spores may also remain viable on skin and hair after an animal recovers from clinical disease. Mice and rodents may further serve as a source of infection by leaving infected hairs around barns.

Ringworm was only recently recognized as a common disease of sheep. Ovine dermatophytosis has been on the increase, especially in the show lamb arena in the United States, where it is referred to as “club-lamb fungus.” A sheep-adapted strain of T. verrucosum has been identified as the etiologic agent. The infection is spread through direct contact with infected animals, contaminated grooming instruments, or infective materials lodged in wood fences and other materials in show barns or farm sites that have held infected lambs. Lesions generally appear a few weeks after contact and begin as clearly demarcated, scaly, scab-covered, or hairless areas on the face, ears, and wool-less areas of the neck, or as matted areas in the wool of unshorn or long-fleece sheep. Lesions vary in size from pinpoints to 3 inches in diameter. Disease is usually self-resolving within in 2 to 4 months after exposure, although wool may not grow back for an additional 2 to 5 months.