7 The coughing and/or dyspnoeic cancer patient

Coughing is a clinical sign associated with tracheal or lung pathology and therefore is suggestive of intrathoracic neoplasia in a cancer patient, whilst dyspnoea can indicate pulmonary, pleural, mediastinal, intra- or extratracheal or laryngeal pathology. It is therefore important to remember that a coughing or dyspnoeic cancer patient may not simply have lung cancer but may be showing signs that could be caused by a variety of different neoplastic processes:

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 7.1 – PRIMARY BRONCHIAL CARCINOMA IN A CAT

Theory refresher

Metastatic lung cancer is considered to be much more common than primary lung cancer with almost any malignant tumour having the potential to spread to the pulmonary tissue by virtue of the anatomical nature of the vascular supply in the lungs. The identification of lesions on thoracic radiographs that could be consistent with pulmonary metastasis should therefore initiate a clinical investigation as to the location of a possible primary tumour. The tumours most often associated with pulmonary spread are malignant melanoma, osteosarcoma, mammary carcinoma and haemangiosarcoma (Fig. 7.1) but any malignant tumour could theoretically spread to the lung, so a thorough clinical examination and appropriate ancillary tests may be required in such cases.

Diagnosis

Having obtained a careful history, the clinical investigation of a patient suspected to have cancer of the lower respiratory tract begins with a thorough physical examination, looking in particular for signs of abnormal breathing along with careful auscultation of the heart and percussion of all the lung fields, as well as a full systemic evaluation of the animal. However, for patients with pulmonary neoplasia the cornerstone of diagnosis in general practice remains careful thoracic radiography and for this, fully inflated (i.e. obtained under general anaesthesia) left and right lateral thoracic radiographs are still considered to be the minimum standard, whilst obtaining three views provides an optimum radiographic evaluation. Patterns commonly seen vary from discrete nodules or individual masses to poorly defined interstitial patterns. Consolidation of individual lung lobes can also be seen, as can enlargement of the tracheobronchial lymph nodes if there is nodal metastasis. However, it is important to remember three factors regarding thoracic radiography of neoplasia:

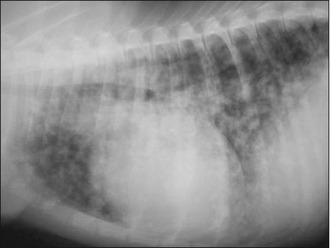

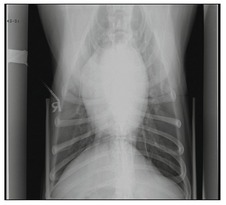

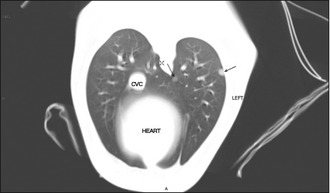

Where available, computed tomography (CT scanning) certainly provides a more sensitive technique for the detection of small lesions, so patients may be considered for referral for this evaluation if possible, especially if a thoracotomy and excisional surgery are being planned and there is uncertainty regarding the clinical stage of the disease. A recent study showed that CT was able to identify enlargement of the tracheobronchial lymph nodes due to the presence of metastatic disease in five cases in which the lymphadenopathy had not been identified on thoracic radiography. However, a different study revealed that although CT provides superior resolution compared to radiography (Figs 7.2–7.4), it is still associated with a significant number of both false-negative and false-positive findings. We have to therefore conclude that we do not have perfect imaging modalities available. So caution must always accompany presurgical evaluation and staging by imaging of a patient with possible lung cancer. However, as the identification of metastatic disease has a significant impact on treatment and prognosis, it is vital to attempt to fully stage these patients and perform the evaluations to the highest possible standards.

Figures 7.2–7.4 Lateral and dorso-ventral (DV) radiographs and a transverse CT scan from a dog with a prostatic carcinoma. The radiographs do not clearly show any metastatic lesions but CT clearly shows the presence of metastatic disease, as highlighted by the two black arrows (Fig. 7.4).

Images courtesy of Dr Ani Avner, Knowledge Farm Veterinary Specialist Referral Center, Israel

Treatment

The first-line treatment for localized primary lung cancer is surgical excision of the lesion by complete lung lobectomy, as illustrated by the cat in this case example. In the light of this, and of the fact that radiographs do not provide a cytological or histological diagnosis, it may be desirable in some circumstances to try to obtain a definitive diagnosis before sending the patient to surgery. Fine needle aspiration of the mass, either by ultrasound guidance or by blind aspiration based on the radiographical position of the mass can be simple and useful. However, there is a risk of iatrogenic pneumothorax and some studies have shown fine needle aspiration of pulmonary masses to have a low diagnostic yield. Bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) can also produce a diagnostic sample and one study has suggested that these are more sensitive techniques than radiography in the diagnosis of pulmonary lymphoma. However, for carcinomas, studies in human medicine have shown that the sensitivity of BAL in reaching a definitive diagnosis varies depending on whether or not the tumour can be visualized, with the diagnostic sensitivity falling when the tumour cannot be seen. It may therefore be best to recommend firstly that a definitive diagnosis before surgery is only sought, if for some reason, it will make a difference to the treatment undertaken, and secondly, that thoracotomy to undertake a complete surgical excision and obtain a histopathological diagnosis is still the optimum treatment if possible. Owners, however, need to be counselled that more extensive disease may be found at surgery even with the most advanced diagnostic imaging investigations having been performed.

To undertake surgery the patient is positioned in lateral recumbency with the affected lung lobe uppermost. A standard or modified intercostal thoracotomy from the fourth to the sixth intercostal space is usually sufficient to allow access to the lung lobe. Lung lobectomy can be performed either by using standard ligation techniques or by using surgical stapling equipment (TA-55 or TA-90; see suppliers, p. 201). The use of stapling equipment significantly reduces surgical time and allows for a secure lobectomy closure. Before the thoracotomy is closed the area is carefully checked for haemorrhage or leakage of air from the collapsed bronchi. This is achieved by flooding the thoracic cavity with warm sterile saline and submerging the surgical site. Any areas of haemorrhage or air leakages should be meticulously sutured. Local lymph nodes should also be inspected and biopsied if enlarged. A thoracic drain is placed after copious lavage and the thoracotomy site closed routinely.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree