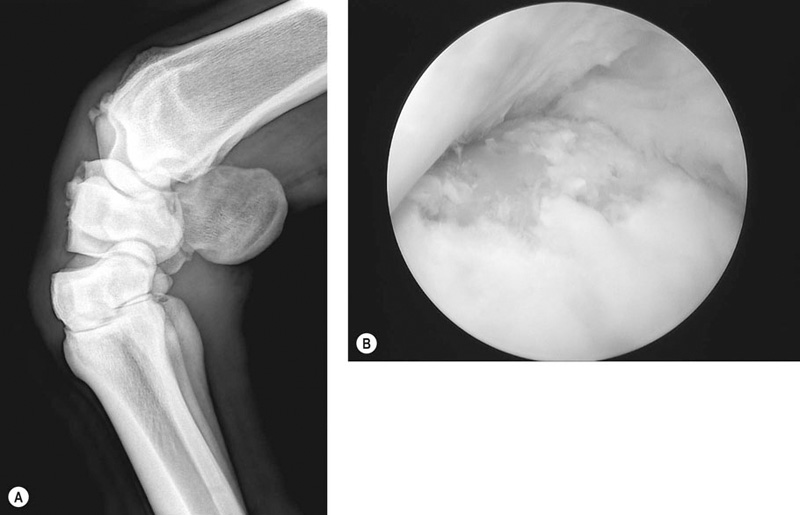

• Variable lameness with synovial effusion. • Radiographs are often unremarkable. • Intra-articular medication is often effective for eliminating signs. • Horses with synovitis often respond well to medical therapy. Advances in ultrasonographic examination of joints have given clinicians a better impression of soft tissue injuries. Because soft tissue injuries can lead to synovitis, documentation of capsular and synovial lining thickening and edema can help not only to diagnose the primary problem but also to monitor therapy over time. Ultrasound also allows the clinician to rule out extracapsular thickenings such as hygromas and synovial hernias. An in-depth review of ultrasonographic examination of joints has been documented.1 Synovial fluid analysis results can be variable in cases of synovitis although most white blood cell counts are less than 1000 cells/mm3 and total protein concentrations are generally between 2.5 and 4.0 g/dL. Biomarker analysis often shows elevated concentrations of prostaglandin E2.2 The lack of radiographic findings, which rules out osteochondral fragmentation and fracture, is often enough to lead to a diagnosis of synovitis, although a negative diagnostic arthroscopy is needed to completely rule out intra-articular ligament disease. It is often difficult to justify diagnostic arthroscopy in cases that are most likely synovitis compared to intra-articular ligament injury; therefore most veterinarians will monitor response to medical therapy. Refractory cases are then easier to justify as needing surgery as synovitis usually responds well to intra-articular medications. MRI is not required to make a diagnosis of synovitis although this condition is readily detectable when performed (Fig. 17.1). Systemic anti-inflammatory medications, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications or intravenous hyaluronic acid, are the simplest forms of therapy which are often very effective for controlling synovitis. However, intra-articular anti-inflammatory medication in the form of corticosteroids and/or hyaluronic acid may be necessary to provide effective treatment. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP) or topical diclofenac sodium can also be used for refractory cases. Physical therapy methods such as ice, hydrotherapy, daily range of motion exercises and walking are often used in addition to medications. Intra-articular morphine (20 mg) with ropivacaine (20 mg) has been used in experimental settings to provide up to 24 hours of pain relief for acute cases of synovitis.3 • Capsulitis often results in joint capsule thickening. • Restricted range of motion is common in cases of capsulitis. • Enthesophytes are often seen on radiographs. Horses with acute capsular changes may show no radiographic changes; however, those horses with capsular tearing, especially at the insertion of the capsule into the bone, will often show enthesophyte formation several weeks after injury. Enthesophytes can vary in severity and location; however, in most equine athletes, especially racehorses, enthesophyte formation on the dorsal aspect of the carpal bones is quite common (Fig. 17.2). Ultrasound examination of the joint capsule in horses with acute capsulitis will often show edema formation within the capsular tissues, and thickening of those tissues. Nuclear scintigraphy may also be helpful in some cases, especially in the vascular and soft tissue phases. CT examination may be of little use in these cases unless a primary osteochondral disease process is leading to the capsular change. As for synovitis, MRI is rarely needed to make a diagnosis of capsulitis but is often seen with this modality (Fig. 17.1). • Chronic disease processes often lead to osteochondral fragmentation. • Synovitis is a common feature of osteochondral fragmentation. • Arthroscopy is the treatment of choice. • The prognosis is dependent on the severity of articular cartilage erosion as well as the presence of palmar carpal fragments. Standard synovial fluid analysis is not beneficial for identifying cases of osteochondral fragmentation. However, synovial fluid markers (specifically type II collagen degradation products) have been shown to increase following OC injury within the carpus and have also been correlated with the severity of injury.4 Other biomarkers have also been shown to increase significantly above exercise related increases5 including prostaglandin E2 concentrations which are raised in synovial fluid following OC fragmentation2. Although not commonly performed, monitoring of these may lend useful information regarding the severity of pathological changes to articular cartilage and the degree of the inflammatory response within the joint. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) has also been shown to be elevated in the urine of horses with osteochondral fragmentation with osteophyte production6 and also in synovial fluid7, but not in joints with osteoarthritis.8 Diagnostic arthroscopy is by far the best means of characterizing osteochondral fragmentation, identifying any associated gross pathological changes to articular cartilage and also has the benefit of allowing for treatment of the disease. In most cases, standard radiographic projections of the carpus including flexed and skyline views, are used for confirmation of disease (Fig. 17.2). The palmar surface of the carpal bones must be closely examined on radiographs prior to surgery so that arthroscopic examination of this area is performed, if necessary (Fig. 17.3). Arthroscopic removal of the fragment and use of anti-inflammatory medications are necessary in treating these diseases. Furthermore, chondral supplementation, be it by intra-articular or systemic means, is also beneficial, especially in severe cases of osteochondral fragmentation. The authors also find physical therapy to be beneficial in these cases, to limit the amount of capsulitis that can accompany osteochondral fragmentation. Selected use of intra-articular triamcinolone acetonide with hyaluronic acid may also be of benefit in some cases.9 Selective use of subchondral micropicking with mesenchymal stem cell therapy as an intra-articular injection may benefit cases with more severe cartilaginous degeneration. The prognosis following arthroscopic removal of the osteochondral fragment varies with articular cartilage erosion severity. In particular, return to racing at equal to or better than before surgery was 71.1% for grade 1 lesions, 75% for grade 2 lesions, 53.2% for grade 3 lesions and 54% for grade 4 lesions.10 Grade 4 lesions (which involve a significant loss of the subchondral bone) have also been repaired with 2.7 mm lag screw fixation with reported success of 68% return to racing.11 In addition the presence of palmar carpal fragments with or without dorsal osteochondral fragmentation has a negative effect on prognosis. When present, these palmar fragments can be a continual source of inflammation and can themselves be associated with cartilaginous degeneration/loss12 and removal should be attempted where possible. Evaluation of post-mortem cases9 has shown that most osteochondral fragments in racehorses are acute manifestations of chronic disease processes. In particular, most fragments occur in areas of stress-induced subchondral bone sclerosis, in which micro damage exceeds healing and acute fragmentation results. Although there is a healing response, as shown by the presence of granulation tissue at these sites, continued training ultimately results in fragmentation through the granulation tissue bed. • Horses with osteochondral fracture often present with significant acute lameness. • Synovitis is a common sign of osteochondral fracture. • Horses with osteochondral fracture are often very responsive to flexion. • Radiographs are recommended prior to performing intra-articular anesthesia, which is often not required for diagnosis.

The Carpus

Synovitis

Recognition

Special examination

Laboratory examination

Diagnostic confirmation

Treatment and prognosis

Therapy

Capsulitis

Recognition

Special examination

Osteochondral fragmentation (chip fracture)

Recognition

Laboratory examination

Diagnostic confirmation

Treatment and prognosis

Therapy

Prognosis

Etiology and pathophysiology

Osteochondral fracture (slab fracture)