5 The cancer patient with sneezing and/or nasal discharge

Nasal neoplasia accounts for 1% of tumours in dogs, is considered less common in cats and has also been reported in rabbits. Therefore, although not particularly common in general practice, such cases can generate a diagnostic challenge for practitioners due to the difficulty in directly visualizing the tumour mass. The prevalence of tumour type varies between dogs and cats (dogs: epithelial > mesenchymal > lymphoid; cats: lymphoid > epithelial >mesenchymal; see Box 5.1) and the clinical signs that nasal cancer patients present with can also vary. However, in the majority of cases the clinical signs will be gradually progressive, meaning that patients presenting with recurring or worsening clinical signs warrant further or repeated evaluation. The increasing availability of advanced imaging modalities such as MRI and CT scanning have improved our ability to make accurate and early diagnoses, so the referral of patients to suitably equipped specialist centres with clinical signs that may be attributable to nasal tumours should be considered if possible.

Box 5.1 Common malignant and benign tumours of the nasal cavity

| Common malignant tumours of the nasal cavity | Benign tumours of the nasal cavity |

|---|---|

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 5.1 – CANINE NASAL ADENOCARCINOMA

Presenting signs

Right-sided uniliateral serosanguineous nasal discharge which progressed to intermittent epistaxis, and sneezing (Fig. 5.1).

Case history

The relevant history in this particular case was:

Diagnostic evaluation

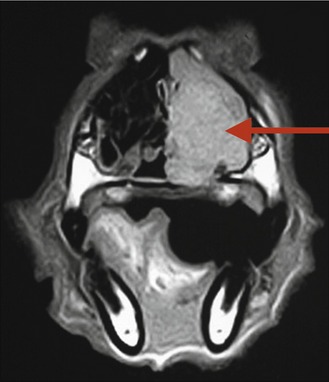

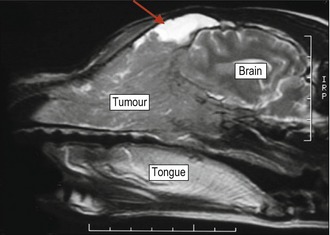

The dog was anaesthetized and an intraoral radiograph was suggestive of the presence of a soft-tissue mass (Fig. 5.2). The dog was then given an MRI scan, which clearly showed the presence of an intranasal tumour as shown in Figure 5.3.

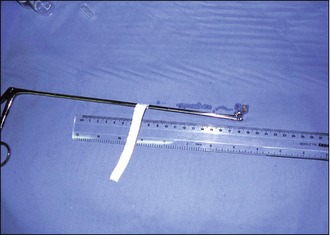

A complete blood count and whole blood clotting time had been assessed and found to be normal before the diagnostic imaging procedure, so whilst remaining under anaesthesia, rigid biopsy forceps were used to obtain several pieces of the tumour for histopathology as shown in Figure 5.4. The histopathology returned to show the mass was an adenocarcinoma.

Theory refresher

Canine nasal tumours are most commonly seen in middle-aged to older dolycephalic dogs but can occur in any breed. Nasal tumours in young dogs would be considered unusual. Medium- to large-breed dogs are more commonly affected and there is some evidence to suggest a possible increase in incidence in dogs living in an urban environment. The initial clinical signs usually involve intermittent unilateral nasal discharge (Fig. 5.5) that progresses over a period typically of 2–3 months to a serosangeous discharge and/or frank epistaxis that may also become bilateral. Occasionally the first presenting sign will be unilateral or bilateral epistaxis or simply a swelling in the region of the nares, nasal planum or frontal sinuses but these signs would be less common as a primary presenting problem. In cases where the tumour is located in either the frontal sinus(es) or the caudal aspect of the nasal cavity, the presenting complaint may initially be considered as a neurological condition (presenting with dullness, depression, head pressing or possibly seizures) but again this would be a less frequent appearance. More commonly, many owners will report that the dog has developed loud snoring or a gurgling sound when asleep and sneezing is also commonly reported. Otherwise many patients will appear normal to their owners in the early stages of the disease.

Figure 5.5 An elderly springer spaniel with typical mucoid nasal discharge associated with a nasal tumour.

Courtesy of Dr Richard Mellanby, University of Edinburgh

Examination

General clinical examination in a nasal tumour patient is often unremarkable but particular attention should be paid to careful visual examination of the nares and palpation along the entire nasal planum, periorbital region and over the location of the frontal sinuses. Nasal airflow should always be assessed in both nostrils (either by placing a chilled microscope slide near the nostrils, or simply assessing whether there is movement of strands of cotton wool) as there is frequently markedly reduced or absent airflow on the affected side. The presence of unilateral nasal discharge or epistaxis is highly suspicious for a nasal tumour in a middle-aged to older medium- to large-breed dog. Other aspects of the clinical examination to evaluate include careful palpation of the submandibular lymph node chain (local metastases are reported to occur in only 10% of patients at initial diagnosis but these cases need to be identified due to the implications for further evaluation and for the treatment) and a visual oral examination.

Diagnostic imaging

Nasal radiographs can be useful to reveal evidence of turbinate destruction and the presence of soft-tissue opacity within one or both nasal chambers, but the use of MRI or CT scanning increases the diagnostic sensitivity and gives clear detail regarding the size and extent of the lesion, factors that can prove to be very important when planning treatment (Fig. 5.6). If advanced imaging techniques are not available then the radiographic views that should be obtained are intraoral or open-mouth oblique views to view the nasal cavity and also a skyline sinus view to image the frontal sinus.

Figure 5.6 The same spaniel as in Figure 5.5, showing the transverse MRI scan of the dog’s nose, confirming the presence of a unilateral left-sided tumour (as shown by the red arrow)

Courtesy of Dr Richard Mellanby, University of Edinburgh

Biopsy

Direct visualization of a mass may also be possible using either a flexible or rigid endoscope. Identification of a mass via any imaging modality, however, does not generate a specific diagnosis, so tissue biopsy for histopathology is always required for definitive diagnosis. Cytological analysis of nasal wash fluid frequently fails to produce adequate samples and therefore this technique should not be relied on as the sole means of diagnosis and is a practice the authors now rarely use, although it can occasionally prove to be useful. Biopsies can be obtained using flexible endoscopic biopsy forceps (although these only produce small tissue samples), cup forceps or a Volkman spoon. When obtaining biopsies it is essential to ensure the tip of the biopsy instrument is not advanced beyond the medial canthus so as to avoid penetrating through the cribiform plate into the cranial cavity. Obtaining these tissue samples will result in haemorrhage that may seem significant, but this usually stops within a few minutes. It is recommended to assess the platelet count and a whole blood clotting time as a minimum data base before undertaking a nasal biopsy procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

months after the signs returned.

months after the signs returned.