6 The cancer patient with halitosis and/or hypersalivation

Hypersalivation and/or halitosis in a cancer patient are usually signs of an intraoral neoplasm and as such, these clinical signs are frequently accompanied by a poor appetite or complete anorexia, especially in the cat. However, drooling saliva may also be indicative of encephalopathy, especially in the cat, which can be caused by hepatic neoplasia, or possibly by an intracranial mass. Oral cancers are considered to be quite common in veterinary medicine, being reported to be the fourth most common malignancy type seen in clinical practice, accounting for 6% of all canine tumours and 3% of all feline tumours. In dogs, the most common tumour type seen is malignant melanoma, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and then fibrosarcoma, whereas in cats, squamous cell carcinomas are the most common, followed by fibrosarcoma. However, many other tumour types have been reported in the literature and a careful histological analysis is required to ensure an accurate diagnosis is made in every case.

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 6.1 – ORAL SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA IN A DOG

Case history

The relevant history in this case was:

Clinical examination

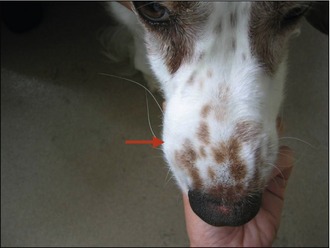

Physical examination revealed:

Differential diagnosis

The submandibular lymph node was enlarged but cytological evaluation of fine needle aspirates revealed this to be due to a reactive lymphadenopathy with no evidence of metastatic disease. In the light of the degree of bony swelling, there was concern that there may be significant tumour invasion into the underlying bone, so an MRI scan was performed (Fig. 6.3). This revealed that the mass had indeed invaded through the nasal bone into the nasal cavity and had actually crossed the midline.

Figure 6.3 Case 6.1 T2-weighted MRI scan revealing the significant intranasal invasion of the oral tumour

Clinical evaluation

A careful oral examination must obviously be performed, even if this requires sedation or a brief anaesthetic to ensure all areas of the oral cavity (including underneath the tongue and in the fauces) have been visualized and examined. In addition to a careful oral examination, attention must be paid to careful palpation of the submandibular lymph nodes and the general condition of the patient, as many oral tumours will have metastatic potential and the possibility of distant disease must always be considered. Some studies have shown that for highly metastatic tumours such as oral melanoma, a significant percentage of cases will have lymph node involvement despite being palpably normal. So if a melanoma is suspected and the primary mass can be excised, excision of the draining submandibular lymph node(s) is also useful from a staging perspective, although no studies have shown such a procedure generates any favourable prognostic advantage compared to leaving the node behind.

Diagnostic evaluation

Once a full staging process has been completed, a biopsy procedure or specific treatment can be planned depending on the outcome of these investigations. The correct treatment may vary depending on the diagnosis and clinical stage reached, so incisional biopsy at surgery remains the first-line method to diagnose the exact nature of most oral tumours (Figs 6.4, 6.5). If it is decided to attempt excisional biopsy, the important fact to remember is that for many oral tumours (with the exceptions of fibrous and ossifying epulides) there is a significant risk of invasion into the adjacent jaw bone, so surgical resection should include bony margins to increase the likelihood of achieving good local control. It is for this reason that it is often sensible to obtain an accurate diagnosis by obtaining an incisional biopsy before attempting excisional surgery. Cats, but especially dogs, generally tolerate partial maxillectomy, mandibulectomy or orbitectomy well and the cosmetic outcomes are good, although this should be discussed with clients carefully beforehand.

Treatment

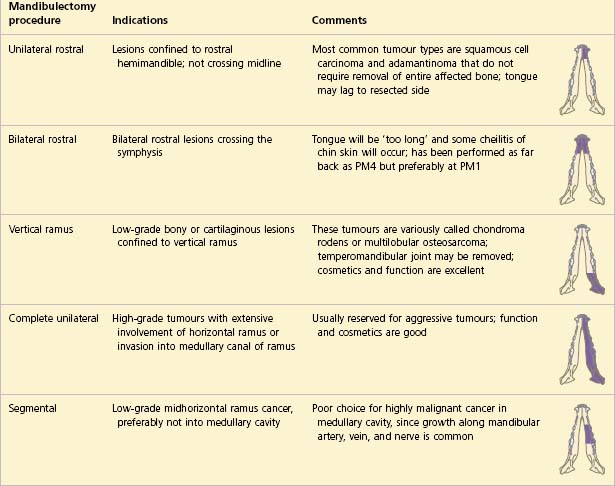

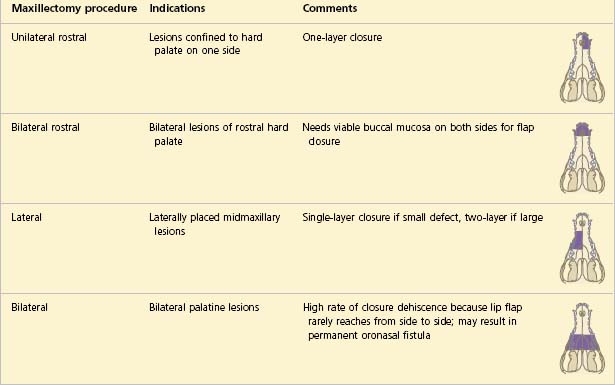

With regard to specific treatment, surgery is usually the most appropriate course of action required for oral neoplasia. Exactly what surgical procedure will be required depends upon the tumour type, the tumour size and the tumour location but it is recommended to try to achieve 2-cm margins (including of the underlying bone) if the mass is confirmed to be malignant. Local segmental excision to include the underlying bone is indicated for all small oral tumours (except ossifying and fibromatous epulides) but larger tumours will require more extensive surgery such as hemimandibulectomy, hemimaxillectomy or orbitectomy procedures (Tables 6.1, 6.2).

The immediate postoperative recovery for canine patients who undergo more aggressive or extensive surgery is usually still rapid with most eating well the evening after their surgery and it is, therefore, not usual for feeding tubes to be placed in the dog (Figs 6.6–6.15).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree