11 The anaemic cancer patient

Anaemic animals can have many underlying conditions causing the problem, so it is vital that a logical, stepwise clinical approach is taken to ensure an accurate diagnosis is reached. The first question to ask once a patient is diagnosed with anaemia is whether the anaemia is regenerative or non-regenerative, as the differential diagnoses to be considered and the diagnostic evaluations to be undertaken will differ once this question has been answered. The determination as to whether a patient has regenerative anaemia or not can be indicated by the presence of polychromasia and anisocytosis on blood smear examination, but the most accurate way is made by assessing the reticulocyte count using a supravital stain such as a new methylene blue (NMB) on a freshly made blood smear. To undertake a reticulocyte count, the clinician should:

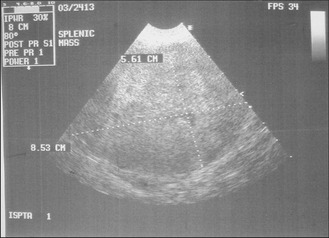

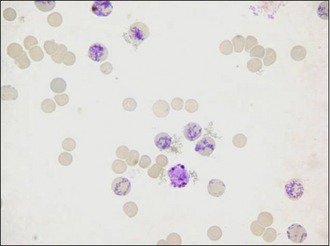

Figure 11.1 The appearance of reticulocytes in a sample of blood taken from a dog and stained with NMB.

Courtesy of Mrs Elizabeth Villiers, Dick White Referrals

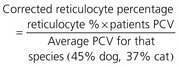

Absolute reticulocyte counts are generally the most useful assessment to make, as percentage reticulocyte values will always be affected by the total red cell count (already low in an anaemic patient). The corrected reticulocyte percentage can help determine whether or not the degree of regeneration is appropriate for the degree of anaemia but this is not always a reliable assessment. The reticulocyte production index, likewise, is a tool to help determine whether or not the degree of response seen is appropriate (Box 11.1).

Box 11.1 The reticulocyte production index

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 11.1 – A HAEMORRHAGING SPLENIC MASS IN A DOG

Clinical history

The relevant history in this case was:

Physical examination

Diagnostic evaluation

Treatment

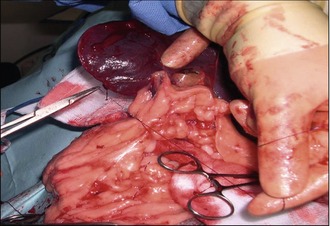

Theory refresher

The diagnosis is therefore usually made based on a combination of clinical history, clinical examination findings and diagnostic imaging findings. If a mass is found within the spleen, then it is often best to recommend not obtaining fine needle aspirates, as if the mass proves to be an HSA, then the act of aspiration itself is likely to cause haemorrhage, thereby substantially increasing the risk of seeding tumour cells throughout the abdomen and establishing metastatic lesions. It is very important to remember that there is a long differential diagnosis list for masses within the spleen (haematoma, haemangioma, splenic nodular hyperplasia, leiomyosarcoma, lymphoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma) and some studies have suggested that up to 45% of splenic masses may NOT be malignant, so obtaining biopsies for histopathology is mandatory. The mainstay of treatment therefore is complete surgical splenectomy, performed via a midline celiotomy but prior to surgery it is prudent to undertake a full coagulation profile (manual platelet count, one-stage prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time or an activated clotting time if available in an emergency, and a d-dimer assessment) as HSA is a tumour that is associated with paraneoplastic coagulopathies such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). The reason for this is that the blood vessels within the tumour itself are anatomically abnormal, which causes platelet aggregation and also significant shear-stress to the red cells as they pass through, which results in erythrocyte damage, such as the formation of schistocytes and/or acanthocytes. In addition to these structural changes, the blood vessels within the tumour often have incomplete endothelial linings, thereby exposing underlying collagen and stimulating the coagulation cascade. All of these changes can lead to inappropriate coagulation and the eventual deregulation of the cascade, causing DIC. A full coagulation assessment therefore is vital. However, once this has been found to be normal, surgery can proceed. The incision should be large (extending from the xyphoid to the pubis) to allow removal of very large splenic tumours and also provide access for a full abdominal exploration which must include the liver, mesentery and local lymph nodes. Any suspicious lesions in these areas should be either aspirated or biopsied at the time of surgery as well. A complete splenectomy rather than a partial splenectomy is indicated with either suspected or confirmed malignant neoplasia.

Splenectomy can be performed either by ligating individual hilar vessels close to the spleen as they enter the parenchyma or it can be performed by ligation of the major splenic vessels (including the short gastric arteries). The latter technique is a much faster and simpler technique and has been shown not to compromise the vascular supply to the stomach. Omental adhesions to the spleen can be bunch ligated and divided (Fig. 11.3). Ligation of the splenic artery and vein is best achieved using a double-ligation technique. A suture material that has good handling properties (e.g. silk) or forms secure ligatures is appropriate for performing this surgery.

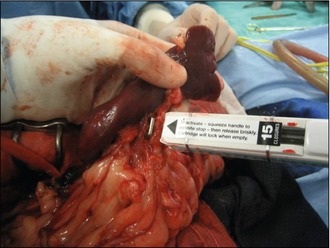

An alternative to suture material is to use vascular clips or a mechanical stapler. The ligating dividing stapler (LDS) is a device that simultaneously places two clips (made of stainless steel or titanium) on a vessel as a blade cuts between them. Each cartridge contains 15 pairs of ‘U’-shaped staples. Vessels that need to be double ligated need to have a single ligature placement before the LDS is applied (Fig. 11.4). This device decreases surgical time by performing rapid vascular occlusion and is extremely useful in splenectomies.

Figure 11.4 The application of an LDS for occluding and cutting between the hilar vessels in a total splenectomy

Postoperative chemotherapy has been considered in many studies and the general conclusion of these is that adjunctive chemotherapy using a doxorubicin-containing protocol definitely improves the outcome for all cases except for small, simple cutaneous tumours for which the prognosis is good anyway. The prognosis for all other forms of haemangiosarcoma is still guarded even with good chemotherapy. Doxorubin has been administered as a single-agent treatment given either at 2- or 3-weekly intervals or in combination with vincristine and cyclophosphamide (the so-called ‘VAC’ protocol) and survival times of between 172 and 250 days are reported, compared with other publications reporting postoperative survival times of 65 days or less without adjunctive chemotherapy. What does become apparent on reading these reports is that the tumour burden and clinical tumour stage are the most important prognostic factors, so as with the other tumours described in this text, it is good clinical practice to establish the clinical stage of the disease using the TNM system (Box 11.2).

Box 11.2 TNM classification and clinical staging for haemangiosarcoma

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 11.2 – A HAEMORRHAGING INTESTINAL MASS IN A DOG

Clinical history

The relevant history in this case was:

days for a PCV of 35%, 2 days for a PCV of 25% and

days for a PCV of 35%, 2 days for a PCV of 25% and  days for a PCV of 15%

days for a PCV of 15%