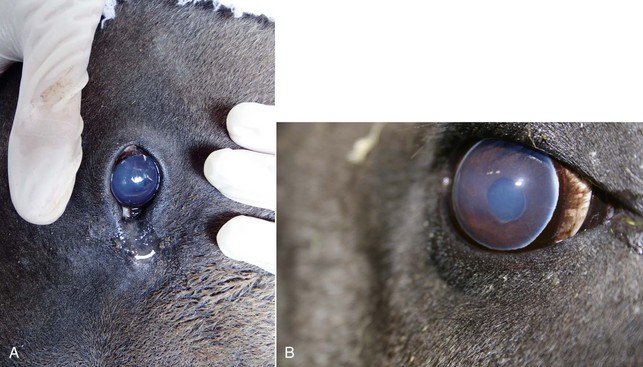

Dawn M. Zimmerman, Sonia Hernandez Tapiridae are a family in the order Perissodactyla that comprises odd-toed ungulates, including horses and rhinoceroses. Tapiridae were once a large group of Neotropical browsers, which largely disappeared at the end of the Pleistocene period;39 currently, four extant species of Tapiridae remain (Table 56-1). Baird’s tapir (Tapirus bairdii), the lowland tapir (T. terrestris), and the mountain tapir (T. pinchaque) are the only New World perissodactyls of Central and South Americas, isolated geographically from the Malayan tapir of Southeast Asia (T. indicus).17 The Malayan tapir has fewer chromosomes compared with South American tapirs (karyotype 2n = 52, compared with 76 and 80) and shares fewer homologies with the American species.23 No hybridization has been described. A fifth living species of Tapirus with the proposed name of T. kabomani has recently been described in the Amazon, sympatric with T. terrestris.13a TABLE 56-1 Biologic Information of the Four Extant Tapir Species Tapirs are primarily crepuscular or nocturnal and are almost exclusively solitary, apart from mother–offspring pairs. Their life span is approximately 25 years in the wild and 35 years in captivity.55,57 As adults, they have few natural predators but are hunted by humans for their meat and hide. Loss of their preferred habitat of old growth forests has further isolated already small populations of wild tapirs, resulting in population decline and reduced genetic variability. The lowland tapir is classified as Vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and CITES Appendix II, whereas Baird’s, Malayan, and mountain tapirs are classified as Endangered by the IUCN and CITES Appendix I.25 All four species are listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. According to the IUCN, less than 5000 Baird’s tapirs and less than 2500 mountain tapirs remain in the wild.25 The Malayan tapir is the largest species (>300 kilogram [kg]), and the mountain tapir is the smallest (approximately 150–200 kg) (Table 56-2). Females are often larger than males, with no other apparent sexual dimorphism.49 Except for the longer, woolly fur of the mountain tapir, tapirs have short hair coats, ranging in color from dark brown or reddish-brown to black. The coat of infant tapirs is a distinct white or yellow striped and spotted pattern to camouflage them against predation. This coloration gradually fades around 5 to 6 months, with adult coloration developing by 12 months of age.47 Tapirs have monocular vision and poor eyesight but good olfactory and auditory senses. All species have brown eyes, often with a bluish cast to them, which is described as corneal cloudiness of unknown etiology and is most commonly found in Malayan tapirs (Figure 56-1). This condition has never been definitively diagnosed in wild individuals and may be associated with excessive exposure to light or trauma in captivity.26 TABLE 56-2 Physiological Parameters and Vital Signs for Adult Tapirs The most notable morphologic feature of the tapir is the muscular proboscis, an extension of the upper lip and nose into a mobile, tactile soft tissue structure devoid of an internal skeleton, making the skull of tapirs unique among perissodactyls.73 Three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) modeling of the skull and images of sinus anatomy are available.13 They have four hooflike nails on the front feet and three on the hind feet. The ancestral front fourth digit, retained from the earliest perissodactyls, is small and does not touch the ground. The tapir foot posture is plantigrade, with splayed toes that help them walk on soft muddy ground. Their mesaxonic limb structure distributes most of their body weight on the third digit.47 The vertebral formula, reported only for lowland tapirs, is 7 cervical, 26 thoracic, 4 lumbar, 6 sacral, and 5 caudal, totaling 48 vertebrae.57 The radius and ulna are separate, and the fibula is complete.47,55 Tapirs exhibit brachyodont, or low-crowned, teeth that lack cement, which is thought to be an adaptation to a diet of soft forest vegetation. Their dental formula is: incisors (I) 3.1, canines (C), 4.3, premolars (P) 3.1, molars (M) 3 to 4.3 (the first premolar may be absent), totaling 42 to 44 teeth. Tapirs have chisel-shaped incisors with enlarged maxillary third incisors, small maxillary canines, and lophodont cheek teeth. Permanent dentition develops by 30 months of age.55 The internal anatomy of the tapir is analogous to the domestic horse (Equus ferus caballus).27 Tapirs have guttural pouches located in the pharyngeal region lateral to the hyoid bones.28,34 The kidneys are nonlobulated, and the cortex makes up 71% to 80% of the renal mass.40 Females have a bicornuate uterus, epitheliochorial placentation, and a single pair of mammary glands. In males, the testes are located cranioventral to the external anal sphincter within a slightly pendulous scrotum62 but may retract into the inguinal canal in lateral recumbency. The penis is directed caudally and capable of spraying urine at distances of 5 meters (m).28,34 Tapirs are monogastric hindgut fermenters, with a large cecum and colon, where all alloenzymatic digestion occurs. Nonglandular squamous epithelium lines the cardia of the stomach, and the remaining gastric epithelium is glandular, especially toward the pylorus.57 The cecum has four fibrous taeniae creating sacculations, and the distal colon has no mesenteric attachments. Like other perissodactyls, tapirs lack a gallbladder. Malayan tapirs normally have anatomic fibrous connective tissue between the visceral and parietal pleurae, as in the elephant, which could be mistaken for adhesions secondary to pleural disease at necropsy.28,33 This homogeneous pleural space connective tissue is not observed in the other three species, which exhibit the mesothelial serous membranes typical of other mammals.27 Proper environmental management of captive tapirs may prevent some of the more common medical problems observed in captivity. Tapirs are typically maintained in outdoor enclosures with an indoor night den. Minimum recommendations include 600 square feet of outdoor space per animal, with off-exhibit individual enclosures measuring a minimum of 12 × 15 feet (180 square feet) or 16 × 16 feet for a female and calf.68 Two-meter high barriers are necessary, as tapirs reportedly climb well.68 In the wild, forested habitat provides safe harbor for hiding or resting;46,68 therefore, artificial habitats should offer adequate vegetation as visual barriers to decrease stress associated with captivity.41 Adult tapirs generally tolerate temperatures from just above 0° C (32° F) to 38° C (100° F),68 but calves should not be exposed to temperatures below 10° C (50° F) until three months of age.1 Even within these temperature ranges, tapirs should be shielded from prolonged exposure to direct sunlight, rain, or wind. At least 25% of outdoor habitats should be shaded, as ocular pathologies and dermatopathies have been associated with exposure to excessive sunlight (Figures 56-1 and 56-2).27 Hard (cement or packed earth) and rough floor surfaces should be avoided in artificial habitats, as they lead to foot problems and chronic lameness (Figure 56-3). Substrates and bedding should be chosen with caution because some substances (e.g., sand and pine shavings) may cause colic and intestinal impaction if ingested, especially in newborns.27 As with other species, coarse hay has been linked with lumpy jaw.68 Wild tapirs inhabit aquatic and riparian regions, therefore a large water source should be provided in captivity for bathing, temperature regulation (cooling), copulation, and defecation. Pools should be large enough for multiple tapirs to submerge; a depth of 4-6 feet with a 1 : 8 slope is recommended.68 Tapirs almost always defecate while standing in water, and lack of access to water has been associated with an increased incidence of rectal prolapse.68 Crowded conditions in captivity may cause chronic stress and abnormal or aggressive social interactions. When considering the addition of conspecifics, enclosure size as well as individual behaviors must be taken into consideration. In particular, aggressive interactions among males may be prevented by separating immature males from adult males at 12 months of age.68 Although tapirs have been successfully integrated into Neotropical and Asiatic multispecies exhibits, caution should be exercised with regard to integration, as tapirs have been known to eat birds.68 Tapirs may be extremely aggressive and have been known to inflict serious harm on keepers and other tapirs. In the wild, tapirs consume a wide variety of woody and nonwoody plant taxa, feeding on various plant parts, including leaves, fruits, grasses, and twigs.46,47 Captive diet recommendations are based on known nutrient requirements of the domestic horse,68 which includes 70% roughages (legume hay, commercial produce, and browse) and 30% concentrates (commercial herbivore pellet).68 Roughage should comprise high-quality alfalfa hay (>15.9% crude protein; <42.8% neutral detergent fiber) or grass hay (>9.8% crude protein; <67.4% neutral detergent fiber).68 Roughage maintains normal gastrointestinal (GI) function, and decreased dietary fiber is linked to problems such as rectal prolapse.27,68 Commercial produce and browse should also be offered, although the latter is lacking in most captive diets.65 Concentrates used to complement nutrition from roughages include high-fiber herbivore pellets with 12% to 18% crude protein.68 Fruits, greens, and root vegetables may be offered in limited quantities. It is important to use these foods sparingly, as excess starch and sugar may contribute to dental disease and obesity,27 which may exacerbate foot, hoof, and chronic joint problems. Tapirs should not be fed directly off the ground, as this may lead to ingestion of foreign bodies and reinfection with parasites.68 Wild tapirs are known to seek out salt accumulations or natural mineral licks,47 but mineral supplementation is not necessary in captive individuals with a balanced diet. However, a salt block may be offered as a supplement or enrichment. No known species-specific trace mineral requirements exist; however, copper and zinc levels should not be lower, and iron not higher, than that recommended for horses.10 Tapirs are highly efficient in calcium absorption, an adaptation to the high calcium-to-phosphorus (Ca : P) ratios of their natural diet; therefore, alfalfa hay is adequate.10 Iron storage disease is prevalent in tapir species. Although a dietary cause has not been identified,6 pelleted compound feeds often contain high levels of iron (Fe),9 and elevations of vitamin C from high fruit intake may promote GI iron absorption.15 Captive tapirs reportedly have much lower serum copper concentrations compared with wild tapirs (Patrícia Medici, personal communication)26 as well as domestic horses,27 although no known pathologies have been reported. Daily food intake for an adult tapir should be 4% to 5% of body weight,68 although pregnant or lactating females and young calves may require a higher intake. Ideal body condition scores in tapirs are maintained at the presumed maintenance energy requirement for hindgut fermenting herbivores (digestible energy [DE] intakes of 0.6 megajoules/dietary energy [DE]/kg0.75/day).12 In the wild, tapirs are continuous feeders, spending up to 90% of their active hours foraging,47necessary to acquire adequate nutrition with their limited stomach capacity.69 Overconsumption at one feeding, especially of nonfibrous foods, may contribute to GI problems (colic, volvulus, torsion, impaction, obstruction, obstipation) or founder.26–28 Enteroliths of vivianite and newberyite structure have been reported, in contrast to the struvite composition normally found in horses.54 To prevent enterolith formation, dietary recommendations for captive tapirs promote carbohydrate fermentation while minimizing protein fermentation in the large intestine.54 Tapirs have traditionally been managed through “direct contact”; however, reports of severe or lethal injuries to caretakers highlight the risks of manual restraint. The current Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) standards recommend that tapirs be managed with “protected contact.”1 The only acceptable type of physical immobilization, which requires training, is the use of a large animal chute.28 Depending on the disposition of individual animals, some tapirs may be trained with positive reinforcement to be moved, to be prompted to present body parts, and to stand still for biologic sample collection or intravenous catheterization. Tapirs may also be “scratched-down” to lateral recumbency, with a coarse horse brush or outdoor broom used to stroke the animal’s dorsum, neck, and the lateral and abdominal walls. Although some have used “scratch-downs” for physical examination, administration of injections, and even repeated blood collection,28 the level of immobilization induced by this “state” should not be exaggerated.35 The recent increase in use of α2-adrenergic agonists, alone or in combination with other drugs, has decreased the need for ultrapotent narcotics such as etorphine and carfentanil. The preferred anesthetic protocol depends on both the environmental setting (i.e., captive or free-ranging) and the individual’s disposition. It is important to establish a quiet environment while working with these animals. If stress is unavoidable (i.e., transport, trauma, or disease), preanesthetic medication is recommended. The success of some anesthetic protocols used for free-ranging tapirs depends on the animal’s degree of relaxation.16,20 Tapirs often retreat into water when threatened, so this should be taken into consideration during immobilizations. It is recommended that the animal be fasted for 24 hours to minimize the potential for regurgitation and minimize the pressure on the diaphragm from the GI tract. Protocols should emphasize maintenance of euthermia, through the heating of enclosures in cold climates or cooling the animal in hot weather. Because tapirs are tropical animals that are rarely exposed to full sunlight, they should not be immobilized in full sun. Preanesthetic agents such as xylazine and butorphanol have been used in tapirs successfully.20 An estimated dosage of butorphanol (0.15–0.25 milligram per kilogram [mg/kg]) combined with xylazine (0.3–0.5 mg/kg) delivered intramuscularly (IM) produces sufficient immobilization. Alternatively, detomidine (0.06 mg/kg) combined with butorphanol (0.15–0.2 mg/kg) has been used successfully in captive Baird’s tapirs.62 It is worth noting that these dosages are less than those required to achieve recumbency in domestic horses. For example, a sick adult lowland tapir was successfully sedated with only 5 mg detomidine hydrochloride and 10 mg butorphanol.59 Anesthetic induction is typically achieved by hand or remote delivery of intramuscular (free-ranging and captive) or intravenous injection (captive animal previously sedated or conditioned). Factors influencing the choice of induction protocol are provided in Table 56-3. Intravenous induction with propofol or ketamine is possible in trained or sedated individuals. Standing sedation with xylazine, alternative α2-agonist combinations, or azaperone (1 mg/kg) may be used for short, less invasive procedures (e.g., skin biopsy, blood collection, portable radiography, etc.).26 Following anesthetic induction, tapirs adopt a saw-horse position, drop their heads, drool, and may lose control of their proboscis; then they progress to a sitting-dog position before achieving recumbency. Isoflurane is the most common inhalant used to maintain anesthesia in tapirs. Intravenous guaifenesin in a dextrose solution has been used safely in a small number of Baird’s tapirs (L. Padilla, personal communication) to increase relaxation, depth, and duration of anesthesia following induction with other agents. At rates used in horses, intravenous guaifenesin provided similar anesthetic effects as well as dose-dependent and rate-dependent respiratory depression. Since guaifenesin susceptibility varies among equid species,44 it should be used in tapirs with extreme caution until additional research has been conducted. Constant rate infusions of propofol have been reported in tapirs,20 and small boluses have been used as supplements to maintain or reach deeper planes of anesthesia. TABLE 56-3 Summary of Protocols Used to Immobilize Free-Ranging Tapirs

Tapiridae

General Biology

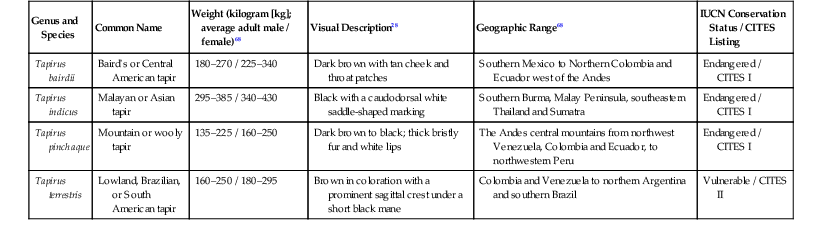

Genus and Species

Common Name

Weight (kilogram [kg]; average adult male / female)68

Visual Description28

Geographic Range68

IUCN Conservation Status / CITES Listing

Tapirus bairdii

Baird’s or Central American tapir

180–270 / 225–340

Dark brown with tan cheek and throat patches

Southern Mexico to Northern Colombia and Ecuador west of the Andes

Endangered / CITES I

Tapirus indicus

Malayan or Asian tapir

295–385 / 340–430

Black with a caudodorsal white saddle-shaped marking

Southern Burma, Malay Peninsula, southeastern Thailand and Sumatra

Endangered / CITES I

Tapirus pinchaque

Mountain or wooly tapir

135–225 / 160–250

Dark brown to black; thick bristly fur and white lips

The Andes central mountains from northwest Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador, to northwestern Peru

Endangered / CITES I

Tapirus terrestris

Lowland, Brazilian, or South American tapir

160–250 / 180–295

Brown in coloration with a prominent sagittal crest under a short black mane

Colombia and Venezuela to northern Argentina and southern Brazil

Vulnerable / CITES II

Unique Anatomy

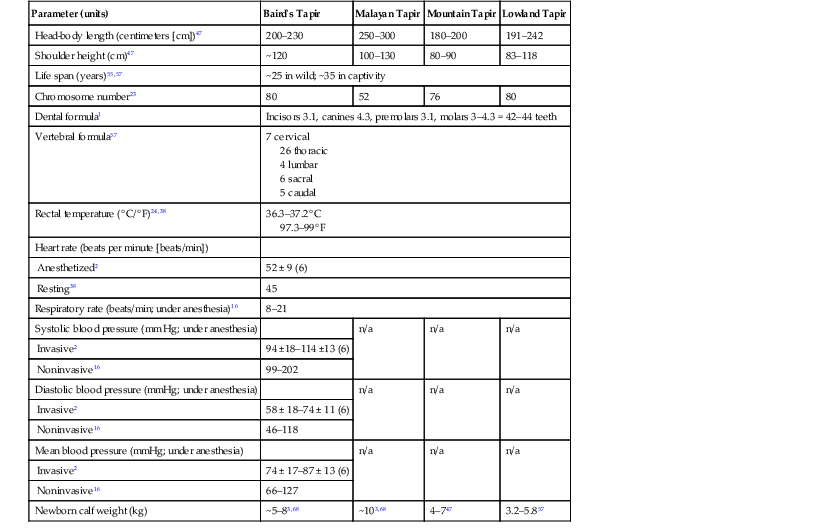

Parameter (units)

Baird’s Tapir

Malayan Tapir

Mountain Tapir

Lowland Tapir

Head-body length (centimeters [cm])47

200–230

250–300

180–200

191–242

Shoulder height (cm)47

~120

100–130

80–90

83–118

Life span (years)55,57

~25 in wild; ~35 in captivity

Chromosome number23

80

52

76

80

Dental formula1

Incisors 3.1, canines 4.3, premolars 3.1, molars 3–4.3 = 42–44 teeth

Vertebral formula57

7 cervical

26 thoracic

4 lumbar

6 sacral

5 caudal

Rectal temperature (° C/° F)24,38

36.3–37.2° C

97.3–99° F

Heart rate (beats per minute [beats/min])

Anesthetized2

52 ± 9 (6)

Resting38

45

Respiratory rate (beats/min; under anesthesia)16

8–21

Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg; under anesthesia)

n/a

n/a

n/a

Invasive2

94 ±18–114 ±13 (6)

Noninvasive16

99–202

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg; under anesthesia)

n/a

n/a

n/a

Invasive2

58 ± 18–74 ± 11 (6)

Noninvasive16

46–118

Mean blood pressure (mmHg; under anesthesia)

n/a

n/a

n/a

Invasive2

74 ± 17–87 ± 13 (6)

Noninvasive16

66–127

Newborn calf weight (kg)

~5–83,68

~103,68

4–747

3.2–5.857

Special Housing Requirements

Feeding

Restraint and Handling

Species

Animal Status

Anesthetics

Comments

Tapirus pinchaque

Captive

Carfentanil (5.4 microgram per kilogram [µg/kg]), ketamine (0.26 milligram per kilogram [mg/kg]) and xylazine (0.13 mg/kg,) intramuscularly [IM])

Reversal: yohimbine (0.2 mg/kg, intravenously [IV]); and naltrexone (100–200 mg/kg, half IV, half subcutaneously [SC])

Six immobilizations of tapirs (1 female, 3 males; 1 juvenile male immobilized 3 times) for footwork, gastrointestinal endoscopy, reproductive surgery52

Tapirus indicus

Captive

Butorphanol (0.15 mg/kg) and detomidine (0.05 mg/kg) OR xylazine (0.3 mg/kg, all IM); use ketamine if needed (0.5 mg/kg, IV)

Reversal: naloxone and yohimbine (0.2–0.3 mg/kg, IV)

Nineteen immobilizations of Malayan and mountain tapirs28

Tapirus bairdii

Captive

Butorphanol (0.15–0.2 mg/kg) and detomidine (0.06 mg/kg); ketamine (1–2 mg/kg) was used to reach or maintain recumbency and light anesthesia

Boluses of propofol (0.2–2.0 mg/kg per bolus) were used to effect as needed

Report of 11 males anesthetized for semen collection by electroejaculation in three captive institutions in Panama,16 but authors (personal communication) report similar usage in similar number of females has the same effects, and that anesthesia was antagonized with naltrexone and yohimbine

Tapirus indicus

Captive

Butorphanol (80 mg, IM) and

Xylazine (120 mg total, IM) OR detomidine (12 mg total, IM)

Reversal: naltrexone (200 mg total, IM), tolazoline (1400 mg total, IM)

Estimated body weight 340 kg; repeated immobilizations of light anesthesia for diagnosis and treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma50

Tapirus terrestris

Captive

Detomidine (0.03mg/kg, orally [PO]), 20 minutes later, carfentanil (1.85 µg/kg, PO)

One animal repeatedly immobilized for wound management; variety of combinations of α2-agonist or etorphine or carfentanil were used but eight immobilizations with detomidine/carfentanil, PO, were most useful.60

Tapirus bairdii

Attracted wild tapirs to bait stations

Total dosage for a 200–300 kg animal: 40–50 mg of butorphanol and 100 mg of xylazine in the same dart

Additional ketamine (187 ± 40.86 mg/animal) or constant rate infusion of propofol (50–200 mcg/kg/min), administered IV

Reversal: Naltrexone 50 mg, with 1200 mg of tolazoline in the same syringe IM; no sooner than 30 minutes from last administration of ketamine

Administered to animals from a tree blind via a dart

The animals had been habituated to come to bait for several days and thus were relatively calm when darted16

Tapirus terrestris

Tapirs were captive, semi-captive or wild

Ketamine (3.5–4 mg/kg) and xylazine (2–2.2 mg/kg) IM, supplemented with ketamine (1.4 mg/kg) IM

Reversal: Tolazoline (4 mg/kg)

Administered using darts projected by a blowpipe, or IV using syringe4

Tapirus terrestris

Wild tapirs captured in pens or pit-falls

Butorphanol tartrate (0.15 mg/kg) with medetomidine (0.03 mg/kg) IM, in same dart

Reversal: Atipamezole (0.06 mg/kg) with naltrexone (0.6 mg/kg) in same syringe, IV

Adequate immobilization for radio collaring, and biologic sampling71

Tapirus terrestris and Tapirus pinchaque

Wild tapirs captured in pens or pit-falls, or immobilized by dart

Dosages were calculated using allometric scaling: ketamine (0.62–0.41 mg/kg) and atropine (0.025–0.04 mg/kg), and tiletamine-zolazepam (1.25–083 mg/kg), and romifidine (0.05–0.03 mg/kg) OR detomidine (0.06–0.04 mg/kg) OR medetomidine (0.006–0.004 mg/kg) in the same dart

Reversal: atipamezole (0.06 mg/kg)

Medetomidine produced best results obtaining good muscular relaxation and more stable cardiopulmonary parameters43 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Tapiridae

Chapter 56