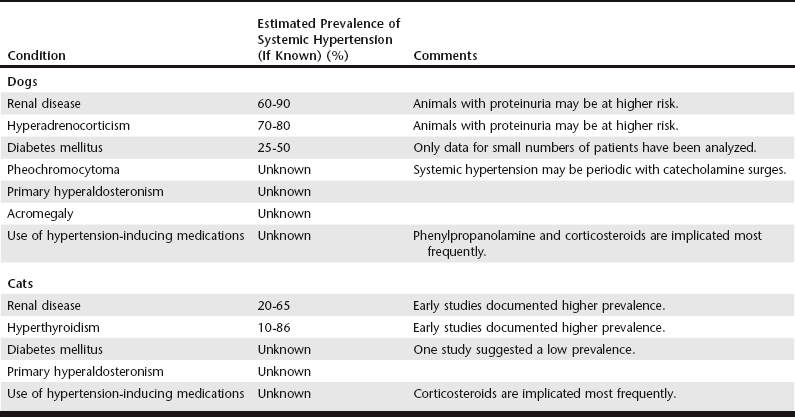

Chapter 169 Persistent elevation of systolic BP to values higher than 160 mm Hg is associated with progressive renal injury in dogs, and the severity of renal injury has been correlated with the degree of elevation (Finco, 2004). Potential renal pathologic changes induced by systemic HT include both glomerular and tubulointerstitial changes with resulting ischemia, necrosis, atrophy, and exacerbation of proteinuria. These gradual and additive changes may be difficult to quantify in living animals with preexisting renal disease, but systolic HT (>160 mm Hg) at the time of presentation increases the odds of uremic crisis and death in dogs with renal disease (Jacob et al, 2003). Systolic BP higher than 180 mm Hg has been associated with ocular injury, including retinal or intraocular hemorrhage; retinal vascular tortuosity; and retinal detachments and retinal degeneration that may cause acute blindness, especially in cats. Neurologic abnormalities, most often intracranial—including seizures, mentation changes, and vestibular signs—have been noted in dogs and cats with HT and are more likely when systolic pressures exceed 180 mm Hg. Although variable cardiac hypertrophy has been documented in cats with naturally occurring HT (Chetboul et al, 2003; Henik et al, 2004; Nelson et al, 2002) and has been shown to regress with successful antihypertensive therapy (Snyder et al, 2001), the degree of hypertrophy has not been shown to correlate with severity of HT. In dogs with experimentally induced HT, hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction without fibrosis occurred within 12 weeks (Douglas and Tallant, 1991). Although congestive heart failure caused by systemic HT appears to be rare in either species, hypertensive veterinary patients may exhibit signs of congestive heart failure or circulatory volume overload in response to excessive intravenous fluid administration. The onset, development, and clinical repercussions of cardiac changes resulting from sustained HT await further study in cats and dogs with naturally occurring systemic HT. Systemic HT may be recognized when BP is measured as part of a diagnostic evaluation in animals known to have, or suspected of having, systemic diseases associated with the development of HT. Alternatively, elevated BP may be detected when clinical signs of HT-related target organ damage (typically retinal detachment or intracranial neurologic signs) lead to BP measurement (Box 169-1). Although periodic BP evaluation in healthy patients has been advocated by some authors, the moderate sensitivity (53% to 71%) and specificity (85% to 88%) of oscillometric and Doppler methods of detecting systolic BP higher than 160 mm Hg in conscious dogs increases the risk of false-positive and false-negative readings (Stepien et al, 2003). However, in cats these concerns may be modulated by the increased prevalence of diseases (chronic renal insufficiency and hyperthyroidism) associated with the development of systemic HT in older cats. Because these diseases may have an insidious onset, annual BP screening of apparently healthy older cats may be warranted. Diagnosis of systemic HT as a complication of systemic disease requires an understanding of the diseases likely to produce systemic HT as a comorbid factor. The rate of HT in the general canine population is thought to be low, approximately 1% to 10% (Bodey and Michell, 1996; Remillard et al, 1991), and the prevalence of HT in the healthy feline population is unknown. In both species, systemic HT is more common in subpopulations affected by particular diseases (Table 169-1). Published prevalence rates are highly variable for many diseases based on the criteria used for diagnosis (i.e., the BP value used as a cutoff for normal), advances in the early recognition of some diseases, and variability in BP measurement techniques. In cats, renal disease is the most likely cause of systemic HT. Renal disease is highly prevalent in the feline population, and HT occurs in approximately 20% to 30% of cats with this disease (Syme et al, 2002). In early studies as many as 86% of hyperthyroid cats had BP above the reference range, but recent evidence suggests that the prevalence rate of HT in hyperthyroid cats is much lower (≈10% to 30%), perhaps as a result of increased screening and earlier detection of hyperthyroidism (before hypertensive complications develop) (Williams et al, 2010). Many elderly cats have both chronic renal insufficiency and hyperthyroidism, which complicates analysis of the prevalence of HT in these diseases. The prevalence of HT in cats with diabetes mellitus is poorly documented, but BP screening in diabetic cats is warranted clinically, especially if proteinuria is present. Other uncommon diseases associated with systemic HT in cats are acromegaly and primary hyperaldosteronism. Numerous studies in dogs support chronic renal disease (especially glomerular disease), hyperadrenocorticism, and diabetes mellitus as the most common disorders associated with secondary systemic HT. Other uncommon endocrine diseases associated with HT in dogs are pheochromocytoma and primary hyperaldosteronism. The use of vasoactive medications such as phenylpropanolamine or corticosteroids may elevate BP primarily or additively with a causative disease. Healthy sight hounds may have resting BP values up to 15 mm Hg higher than other breeds of similar size (Bodey and Michell, 1996) and should be assessed accordingly. Studies of human hypertensive patients indicate a progressive increase in risk of target organ damage as BP increases above normal values. Although antihypertensive therapy is indicated in an individual patient as soon as target organ damage begins to occur, in veterinary patients the pressure at which an animal begins to sustain end-organ damage is usually unknown. Since recognizable injury to various organ systems has been documented when systolic BP exceeds 160 mm Hg over the long term, antihypertensive medications currently are recommended for patients in this group (Brown et al, 2007). It is likely that this current cutoff value will change as more information becomes available. Target organ injury most often is manifest as ocular injury (retinal hemorrhage, hyphema, retinal detachment), neurologic signs (intracranial signs of depression or obtundation), renal injury (proteinuria, decreased renal function), or cardiac remodeling (left ventricular concentric hypertrophy). Ocular injury is prevalent and easily detectable in hypertensive dogs and cats (LeBlanc et al, 2011; Maggio et al, 2000); for this reason, a complete ocular examination should be performed in any patient in which systemic HT is detected. (Similarly, identification of retinal lesions in a mature cat or dog with a murmur or gallop indicates the need to assess BP carefully). If elevated BP is documented at a single session and no clinical signs of HT (ocular or neurologic) or obvious target organ injury is present, BP measurement should be repeated, preferably within a week. If elevated BP is confirmed, a detailed diagnostic evaluation should be initiated to search for a causative disease (Box 169-2). If a known causative disease is evident when elevated BP first is detected, therapy for HT can be started immediately in conjunction with optimal management of the underlying disorder. If systolic BP is between 160 and 180 mm Hg and no clinical signs of HT are present, BP may be monitored until the diagnostic evaluation is complete. If BP remains elevated and causative disease is found, treatment of the underlying disease (e.g., hyperadrenocorticism) can be pursued concurrently with medical management of HT. If thorough diagnostic evaluation fails to reveal a causative disease, animals with consistently elevated BP should be treated with antihypertensive medications and monitored for development of systemic disease or complications.

Systemic Hypertension

Overview of Systemic Hypertension in the Population

Diagnosis of Systemic Hypertension

Systemic Hypertension