CHAPTER 10 Synovial Fluid

Diseases of the legs and feet comprise a major segment of equine practice. Many diseases causing lameness involve joints, and synovial fluid analysis is often an important part of the diagnostic process in such cases.

Normal synovial lining consists of fibrous and adipose connective tissues covered incompletely by a lining of intimal cells. Within the connective tissue is a highly vascular network of fenestrated capillaries. The lining cells are not true cells residing on a basement membrane. Instead, they rest directly on the fibrillar network of the underlying connective tissue. Two types of cells have been identified in synovial lining; these have been designated as type-A and type-B lining cells. Type-A cells are phagocytic and more numerous. Type-B cells are thought to secrete hyaluronic acid.1

Characteristics of Normal Synovial Fluid

Cellular Composition

Nucleated Cell Count: Total nucleated cell counts of normal equine synovial fluid have been reported to vary widely from one joint to another. Though counts over 2,000 cells/μl have been reported for fluid from the temporomandibular joints of clinically normal animals, fluid from the more commonly sampled limb joints of healthy horses usually contains less than 500 nucleated cells/μl.2,3

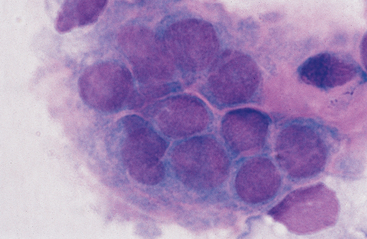

The most obvious differences in reported values are in the proportions of mononuclear cells. Most mononuclear cells in normal synovial fluid are lymphocytes and large mononuclear cells. The latter include monocytes/macrophages and, probably, some synovial lining cells. It may be possible to distinguish synovial lining cells from macrophages in cytologic preparations. Some cells that have been classified as “clasmatocytes” are probably synovial lining cells. Intact clumps of synovial lining cells are occasionally aspirated (Fig. 10-1). In our laboratory, mononuclear cells in synovial fluid are routinely classified as lymphocytes or macrophages. Macrophages usually predominate, though the proportions of macrophages and lymphocytes vary from one joint to another.4 The relative proportions of lymphocytes and macrophages seldom provide useful diagnostic information. Some laboratories routinely report all lymphocytes, macrophages, and synovial lining cells under the heading of “mononuclear cells.” Eosinophils occur infrequently (<1% of total cells) in normal equine synovial fluid.

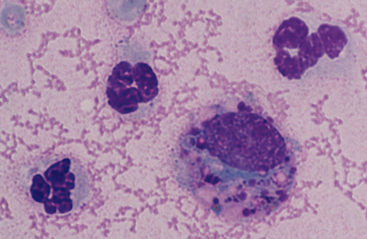

The size of macrophages and degree of cytoplasmic vacuolation in synovial fluid vary widely. Some macrophages have relatively dark blue cytoplasm with few or no vacuoles. Other macrophages, often the larger ones, have numerous clear cytoplasmic vacuoles. Some of this vacuolation is an artifact caused by delayed processing of the fluid after collection. Another morphologic feature of some synovial fluid macrophages is the presence of few to many metachromatic cytoplasmic granules (Fig. 10-2).

Techniques for Examination of Synovial Fluid

Synovial Fluid Collection

Synovial fluid can be aspirated from most joints with a 1-inch, 18- to 20-gauge needle. The skin should be prepared by clipping the hair and performing a surgical scrub to avoid introducing bacteria into the joint. Ethyl chloride spray may be used, if needed, on the overlying skin to lessen the sensation of the needle penetration. Fluid for cytologic evaluation should be placed in an EDTA tube. Note, however, that EDTA interferes with the mucin clot test. If a mucin clot test is to be run, another aliquot of synovial fluid should be placed in a tube with no anticoagulant (eg, red-top tube) or one containing heparin.

Mucin Clot Test

Hyaluronic acid content has been measured directly in synovial fluid, but this test is not performed in most clinical laboratories.5

Total Protein Concentration

Most plasma proteins, especially those with higher molecular weight, are excluded from synovial fluid by the dialyzing properties of the synovial membrane and hyaluronic acid in the perisynovial connective tissue. Some glycoprotein is synthesized by the synovial lining cells and secreted into the fluid. Values reported in the veterinary literature for the protein concentration of normal equine synovial fluid vary widely. One author, using the biuret technique, reported a reference range of 0.92 to 3.11 g/dl.6 Another investigator reported a reference range of 0.5 to 1.0 g/dl using the Coomassie blue method. This latter author attributed the different results to methodologic differences.7 In limited comparisons, we have found that the biuret and Coomassie blue methods yield very similar values and that these values are in the range reported above for the biuret method.

Refractometric measurements have also been used to qualify protein in equine synovial fluid.8 While refractometry has been suggested by some to provide at least an index of synovial fluid protein concentration, others have criticized its use.3,9

Other Tests

In addition to direct measurement of hyaluronic acid content, other chemical tests that have been performed on equine synovial fluid include measurement of creatine kinase and lactate dehydrogenase total activity and isoenzyme activity, alkaline phosphatase activity, and glucose content.6,10 None of these has been used widely in diagnosis of joint disease in animals.

Nucleated Cell Counts

Nucleated cell counts of synovial fluid can be determined manually with a hemacytometer or automatically with an electronic cell counter. The techniques give similar results with canine synovial fluid.11 Because normal equine synovial fluid often has a much lower nucleated cell count than feline or canine synovial fluid, the validity of electronically determined counts on some equine specimens is open to question. Cell counts of synovial fluid from normal equine joints may be so low that they are below the background threshold level of electronic cell counters. Manual electronic counters can provide accurate counts on specimens with at least 500 cells/μl. If the electronically determined count is near the threshold level of the instrument, a manual count should be performed.

It may be difficult to obtain counts on markedly exudative specimens because of the presence of cell clumps, fibrin, and necrotic debris. Another potential technical difficulty is that cell counts of routinely diluted synovial fluid may be falsely low because the viscous synovial fluid does not mix evenly with the diluent in the pipette. Pretreatment of such synovial fluid with hyaluronidase reportedly causes an apparent increase in the cell count of more than twofold.12 This technique is not routinely used in most clinical laboratories.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree