CHAPTER 6 Gastrointestinal Tract

Gastrointestinal disorders account for approximately half of all equine medical problems.1 Cytology can be an invaluable quick, inexpensive aid in the diagnosis of these disorders. Sample procurement has previously limited gastrointestinal cytology to the evaluation of thoracic and abdominal fluid (Chapters 8 and 9), necropsy specimens, and fecal material. Endoscopy, laparoscopy, and ultrasonography have made visualization and biopsying of gastrointestinal lesions physically and economically possible.2–6 Therefore, antemortem sampling of the gastrointestinal tract has become not only feasible but also an integral part of complete diagnostic workups.

Sampling

There are authoritative texts describing endoscopic and ultrasonographic techniques.2–7 Briefly, with endoscopes that are 3 meters in length, the esophagus, stomach, and proximal duodenum of most adult horses can be examined. Restraint may be minimal (twitch or light sedation), depending on the horse. Fasting is not required for esophagoscopy if anesthesia is not used.

Esophagoscopy is commonly performed by nasopharyngeal placement. Advance the scope smoothly and observe the characteristic whitish esophageal mucosa of a collapsed esophagus. If esophageal placement is uncertain or tracheal rings observed, withdraw the scope and make another attempt. Never force the endoscope without knowing its course. Pharyngo-oral retroflexion is a serious risk to equipment, and esophageal perforation is a serious risk to the horse. Examine the stomach along with the esophagus because gastric lesions frequently accompany esophageal lesions. For adequate visualization of the stomach in the adult horse, withhold food for at least 12 hours and water for 6 hours if the horse can tolerate water deprivation.6 To examine the duodenum, pass the endoscope along the greater curvature of the stomach and through the pylorus. This takes patience and experience. For colonic and rectal endoscopy, remove the feces either manually or, in small horses, using an enema. Pass a well-lubricated endoscope into the rectum. Air insufflation distends the esophagus or gastrointestinal tract for better mucosal visualization, especially for ulcers. Transrectal (5 MHz) and transabdominal (2.5 to 3.5 MHz) ultrasonography can be used to visualize and take a transcutaneous aspiration or punch biopsy of a mass.8

Cytologic Features of Normal Tissues

Esophagus and Stomach

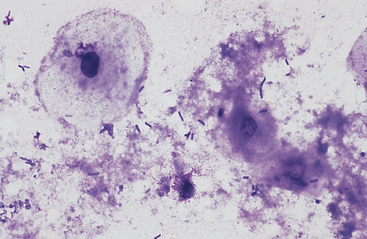

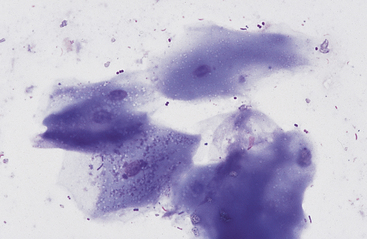

The esophagus and nonglandular anterior region of the stomach are lined by stratified squamous epithelium (Fig. 6-1). A keratinized thick outer stratum corneum overlies the deeper stratum granularis (flattened cells with shrunken nuclei and large basophilic staining cytoplasmic keratohyaline granules), stratum spinosum (flattened cuboid cells), and stratum basale (columnar cells).1 Superficial epithelial cells are large cells with abundant pale blue homogeneous cytoplasm, angular cytoplasmic borders, and sometimes small, dense, round to oval nuclei. Bacteria can adhere to the surfaces of these epithelial cells, but inflammatory cells are lacking. Deeper samples may contain some basal epithelial cells, which are round with darker blue, slightly granular cytoplasm, larger ovoid, nuclei, and a higher nucleus to cytoplasm (N:C) ratio.

Fig. 6-1 Squamous epithelial cells scraped from stomach of horse.

Bacterial flora are seen on surfaces of some cells. (Wright-Giemsa stain)

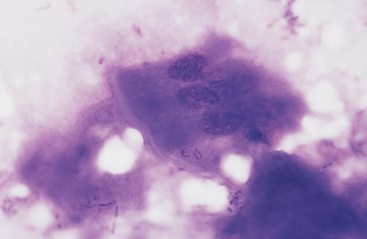

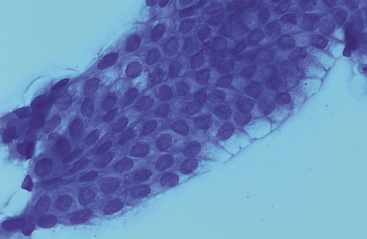

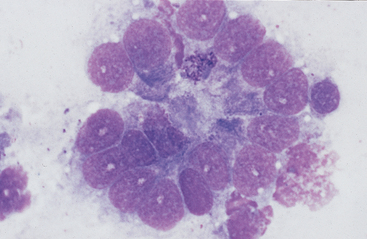

Grossly, the margo plicatus forms a distinct boundary between the white-pink squamous region and the reddish glandular region of the equine stomach. The equine glandular stomach is lined by tall, periodic acid–Schiff–positive columnar epithelial cells that overlie deeper chief cells, parietal cells, mucous neck cells, and rare enteric endocrine cells.1 Cytologic preparations from the glandular region of the stomach contain clusters and sheets of a uniform population of columnar epithelial cells. On low magnification the cells may have a honeycomb appearance (Fig. 6-2). Individualized cells exhibit a columnar shape with basal, round to oval nuclei, stippled chromatin pattern, and pale blue granular cytoplasm. Surface microvilli may give the apical margin a feathery appearance (Fig. 6-3).

Fig. 6-2 Sheet of columnar epithelial cells from pyloric portion of stomach.

The uniform size and shape of the cells give this cluster a honeycomb appearance. (Wright’s stain)

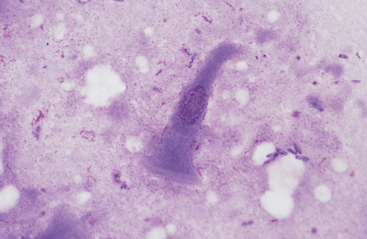

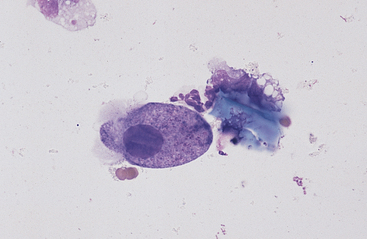

Fig. 6-3 Columnar epithelial cell imprinted from glandular region of stomach.

Cell has oval, basal nucleus and pale-staining microvillus apical border. (Wright-Giemsa stain)

Gastric fluid pH in the horse is variable. The horse appears to be a continuous, variable gastric hydrochloric acid secretor with intermittent periods of spontaneous alkalization.9 Duodenogastric reflux, which is common in the horse, can contribute to this alkalization. Gastric fluid pH values are typically less than 2.0 during feed deprivation but can be greater than 6.0 after free access to timothy grass hay.9 Cytologic examination of gastric fluid contains exfoliated and degenerating squamous and columnar epithelial cells, mixed population of bacteria, and possibly plant material (Fig. 6-4).

Small and Large Intestine

Both small and large intestinal mucosal cells resemble stomach glandular epithelium (Fig. 6-5). Cells are columnar with pale blue, slightly granular cytoplasm, basal oval nuclei, and striated border composed of apical microvilli. Goblet cells, which have a vacuolated pale staining appearance and eosinophilic staining mucus, are more common in the colon and rectum (Fig. 6-6). Squamous epithelial cells are associated with the terminal rectum and anus. Endocrine cells, Paneth cells (pyramidal-shaped cells with prominent apical, spherical, acidophilic granules), and Brunner’s gland cells (Alcian blue–positive submucosal serous-type intestinal glands) are present in the small intestine and granular cells are present in the colon, but these cells are infrequent and have not been cytologically described (Figs. 6-7 and 6-8).1 A few lymphocytes are often seen in intestinal specimens from horses because of Peyer’s patches and submucosal lymphoid tissue. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages have also been reported in the lamina propria of clinically normal horses.10 Although neutrophils were not present in the surface epithelium of the equine rectum, scattered neutrophils and eosinophils have been reported in the rectal lamina propria of healthy horses.11

Fig. 6-6 Cluster of pale-staining goblet cells from colon of horse.

Note small central to eccentric nuclei and abundant clear to vacuolated cytoplasm. These cells are most prominent in the large intestine. (Wright-Giemsa stain)

Fig. 6-8 Higher magnification of colonic epithelium.

A small granular cell with fine azurophilic granules is seen toward center of cell cluster. (Wright-Giemsa stain)

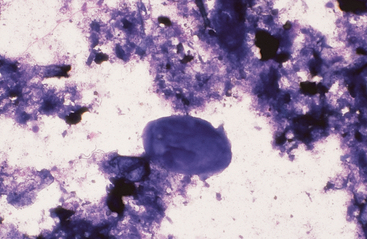

Intestinal fluid contains low numbers of squamous epithelial cells from the esophagus and stomach, a few columnar epithelial cells from the intestinal mucosa, a mixed population of bacteria, protozoa, fungal elements, food material, and rare to no inflammatory cells (Figs. 6-9 to 6-11). Minimal information is available on the microbial population inhabiting the gastrointestinal tract of the healthy horse. Proteolytic bacteria comprise a high proportion of culturable bacteria in the equine gastrointestinal tract.12 Mean pH values reported for the equine duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and hindgut are 6.32, 7.10, 7.47, and 6.7, respectively.12

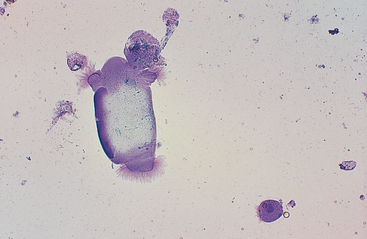

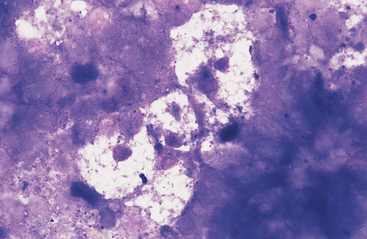

Fig. 6-10 Normal equine protozoa.

Large intestinal fluid illustrating the pleomorphic appearance of normal equine protozoa. Note large size of protozoa compared to red cells. Some plant material and cellular debris are adjacent to protozoa. (Wright-Giemsa stain)

Cytologic Features of Abnormal Tissues

Neoplasia

Neoplasia of the gastrointestinal tract of horses is uncommon and usually occurs in older horses, except for lymphoma, which often occurs in younger horses (Table 6-1). General clinical signs associated with equine gastrointestinal neoplasia include weight loss, anorexia, lethargy, intermittent colic, intermittent fever, and variable fecal consistency. Clinical laboratory findings can include malabsorption (decreased glucose and d-xylose absorption), hypoalbuminemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, anemia (hemorrhage and chronic disease), and hypercalcemia (lymphoma and squamous-cell carcinoma). Peritoneal fluid frequently has an increased nucleated cell count (neutrophilic inflammation), increased protein, and, sometimes, exfoliated neoplastic cells. Microorganisms from the gut lumen may invade gastrointestinal neoplasms, resulting in abscessation and secondary septic peritonitis.

TABLE 6-1 Tumors of the Equine Gastrointestinal Tract

Esophagus | Cecum |

Squamous cell carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma with/without osseous metaplasia |

| Myxosarcoma |

Stomach | Colon |

Squamous cell carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma with/without osseous metaplasia |

Adenocarcinoma | Lymphoma |

Leiomyosarcoma | Lipoma |

Leiomyoma | Lipomatosis |

Gastric polyp | |

Small intestine | Rectum |

Lymphoma | Lymphoma |

Adenocarcinoma | Lipoma |

Leiomyoma | Leiomyosarcoma |

Leiomyosarcoma | Polyps |

Adenomatous polyposis | |

Lipoma | |

Carcinoid |

Data from Barker et al: in Jubb et al: Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed 4, Vol 2. San Diego, 1993, Academic Press, pp 33-317; East and Savage: Abdominal neoplasia (excluding urogenital tract). Vet Clin North Am (Equine Pract) 14:475-493, 1998; Orsini et al: Intestinal carcinoid in a mare: an etiologic consideration for chronic colic in horses. JAVMA 193:87-88, 1988; Patterson-Kane et al: Small intestinal adenomatous polyposis resulting in protein-losing enteropathy in a horse. Vet Pathol 37:82-85, 2000.

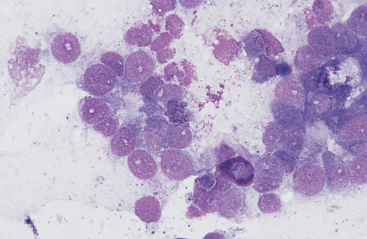

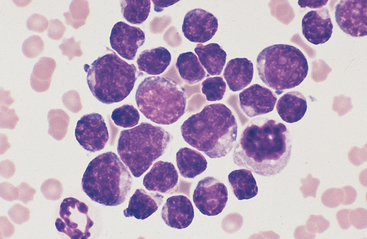

Lymphoma is the most common malignant neoplasm of the equine gastrointestinal tract.8,13 It occurs most frequently in the small intestines and may be a primary alimentary lymphoma or a multicentric lymphoma that involves the intestines in addition to peripheral lymph nodes and/or the thoracic cavity. Alimentary lymphoma is associated with local to diffuse thickening of the gut wall and marked enlargement of the mesenteric lymph nodes.14 Neoplastic infiltrates can extend from the lamina propria and submucosa to the serosal surface. The lymphocyte population can vary from sheets of lymphoblasts or granular lymphocytes to a mixed population of large and small lymphocytes (Figs. 6-12 to 6-15).14–18 Cytoplasmic granules in granular lymphoma cells are readily seen on cytology but may be poorly visible on histopathology.15 Plasmacytoid cells and plasma cells can be abundant, and giant cells can occasionally be seen in the gut wall and lymph node of horses with lymphoma.13,14

Fig. 6-12 Equine intestinal lymphoma.

Note mixed population of large, intermediate, and small lymphocytes with coarse chromatin pattern, indistinct nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm. (Wright-Giemsa stain)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree