19 Syndromes in equine dermatology

Alterations in hair quality and quantity (hair follicle disorders and alopecia)

Cutaneous nodules (the ‘lumpy’ horse)

Scaling and flaking (dry dermatoses/seborrhoea) syndrome (the ‘scaly’ horse)

Weeping and seeping/crusting (wet) dermatoses (the ‘eczematous’ horse)

Coronary band disease (coronitis syndrome)

I have six honest serving men,

their names are What and Why and When

From: The Just So Stories (1902) by Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936)

Key to coloured tables

Pruritus (the itchy horse)

Pruritus can be defined as the (unpleasant) sensation that encourages the animal to itch and is one of the commonest dermatological clinical presentations. It is vitally important to recognize that pruritus is a phenomenon attributable to both central and peripheral neural mechanisms (Blood & Studdert 1988). Nerve endings in the region of the dermo-epidermal junction transmit the sensation of ‘itchiness’ via slow-conducting C-fibres to a central region where the itch sensation is modulated. ‘Scratching’ at the site of itch is transmitted via fast conducting fibres and results in a temporary suppression of the sensation by down-regulating the peripheral input (the so-called Wall’s gate phenomenon). Pruritus is a common symptom of local peripheral and central pathology and can be triggered by many factors. In addition pruritus such as that associated with insect bites in particular may continue until there is a marked local inflammatory response arising from self-trauma. Only then does the pruritus abate – preventing self-trauma can therefore prolong the ‘itchy’ state. A diagnostic complication can therefore arise when the pruritic state results in masking of the original signs and this aspect should not be forgotten.

The extent or severity of the pruritus exhibited by an individual animal is very variable – there is no consistent degree of pruritus for any particular condition. Some horses will show mild signs with severe disease and others will show marked pruritus with mild disease of the same type. This is possibly the main reason why grading pruritus has not gained any credibility in horses at least; however, a scale of 0 (no itch) to 10 (extreme itch) has been suggested and it can sometimes be helpful in assessing progression and the effects (positive or negative) of therapeutic interventions in a particular individual (Scott & Miller 2003). This can be difficult to apply when there is variability of signs at different sites and under different conditions such as warmth, cold, etc. Often the severity of the itching can be determined – sometimes simply by asking the owner and at other times by assessing the severity of the secondary changes. Thus, an animal with a severe localized allergic response to the bite of an insect may cause severe self-trauma at the site – often the induced skin damage and inflammation is more extensive than the original bite/sting or insult. Pruritus can therefore be self-perpetuating and triggered by a relatively minor episode of intense itchiness. This can be followed by rubbing, biting and self-mutilation which, in turn, cause further local inflammation and irritation. The instigating factor may not therefore be present at the time of the examination or may be significantly masked by the changes. Most pathologists do not relish the assessment of a chronically rubbed/itched and self-traumatized skin. The more prolonged the effects the more difficult it is for the clinician to be sure of the original cause and the more damaged the skin the less the pathologists will be able to glean from biopsies (Fig. 19.1).

The location of the ‘itching’ can, however, be a marker for the location of the pathology but there are some circumstances such as rabies, for example (see Fig. 15.2), when the clinical response can be referred, i.e. the pathology is in a different place to the itch. Similarly, head-shaker horses often rub the side of the face suggesting pruritus but this may be a response to pain or irritation within the nasal cavity, or to numbness or to ‘tingling’ sensations (see Fig. 15.3). If the horse could just tell us where and what it is feeling, the diagnosis of pruritus in horses would be far simpler!

Cutaneous infections may also cause self-itching – it is important to differentiate this from a pain response; some horses will bite or chew at a painful locus. Bacterial infections do rarely cause pruritus but the fungal infections (superficial dermatophytosis) or deep (mycetoma) are somewhat more likely to be pruritic. In the former case itch is not one of the main signs but gentle (and carefully protected) rubbing of the lesion may elicit the ‘pleasure’ response manifest by muzzle twitching, grimacing and arching of the back towards the site. Deep fungal conditions such as pythiosis (see p. 183) can cause enough irritation to cause severe self-trauma.

The site of the itching is usually a really good indicator of the location of the problem. A horse affected by the spinose ear tick (Otobius megnini) or aural (Otodectes) spp. mites or the bites of the Simulium fly (see p. 210) or certain species of Culicoides may itch and worry at the ear and indeed an affected horse may develop a non-neurological head-shaking syndrome with rotatory movements of the head and ‘ear shaking’. A common symptom in equine practice is perineal itching. Here the differential diagnosis may include the insect bite hypersensitivity (‘sweet itch’) syndrome, lice (the tail base being one of the preferred sites for both the major species of louse), or oxyuriasis (due to the combined effects of adult worm activity in and around the anus and perineal skin as well as the presence of the eggs). There are several species of fly, such as Hippobosca equinum (see p. 210) and Haematobius spp., and some mosquitoes that prefer to feed at this site also. The physical presence of the insects may be enough to cause localized worry but there may also be some direct localized hypersensitivity responses.

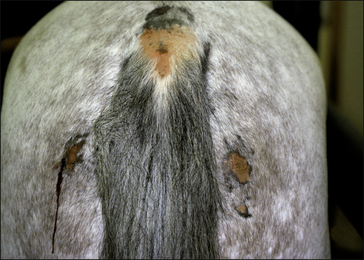

Another quite common perineal or rump rubbing/’pruritic’ condition is associated with the accumulation of skin debris and grease in the intermammary region of mares. It is always therefore worth checking for this condition in a mare that rubs her rump region (Fig. 19.2).

There are also a few conditions that are characterized by pruritus with minimal or at least easily overlooked reasons. For example, there are horses that have a psychogenic itch – these cases may be distracted from the ‘neurosis’ (see p. 331). A well-recognized form of this occurs in bored stallions where they develop a so-called ‘self-mutilation syndrome’; they will actively bite and chew at a defined location (often on the flank or stifle region). It is very important to investigate such cases very thoroughly because there are significant differences in management and treatment between the various diagnostic possibilities.

Investigation of the pruritic horse

A full general history should be obtained during which the presence of systemic disease or other chronic conditions and any concurrent medications that may mask or alter the clinical signs may be identified. For example, it might be possible to establish that the horse had been losing significant weight recently; the non-dermatological signs may be due to a second disease but they may be part of a wider syndrome. In the latter case the skin may be the best and possibly the only visible indication of a systemic disorder. A suggested list of preliminary questions is shown in Table 19.1.

Table 19.1 The significant aspects of the clinical investigation of a pruritic horse

A further fundamental question is related to the presence of a defined lesion prior to the onset of itching or whether any visible lesion actually developed after the pruritus. The latter may be due then to self-trauma and subsequent biopsy of this region may be very misleading (see Fig. 19.2). This can be very difficult to establish simply because the owner may not have examined the horse closely enough to detect a lesion before or soon after the horse started to rub or scratch the site. It is possibly unfair to expect owners to be able to answer this question but if it can be answered it is a big help.

As might be expected, a full dermatological examination must then be performed (see p. 25). This is particularly important because of the possibility of helpful signs in other body systems. An old horse affected, for example, by pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID/equine Cushing’s disease) may show characteristic features and this condition may suppress immune processes sufficiently for ectoparasites and bacterial skin diseases to develop. Failure to recognize the underlying primary condition may waste time, effort and money. It is often very helpful for the veterinarian to observe the responses that the horse shows; if this cannot be achieved within the normal time scale of a clinical visit a video recording taken by the owner may help enormously; there are ‘secret scratchers’ who only show the signs when they alone and others that only show the signs at night! Of course such a manifestation may be a strong indicator of possible causes also. A horse that rubs or scratches its legs and face when it is only in a stable may be exposed to biting or worrying parasites in the bedding.

As pruritus is simply a sign of many possible diagnostic options, further samples and diagnostic tests are commonly undertaken. The commonest overall cause of pruritus in the absence of a defined pre-existing lesion in the general population are the ectoparasitic conditions and so a common early test is the collection of brushings from both affected zones and from the animal generally (see p. 60).

No diagnostic technique can be completely precluded from an investigation of the pruritic horse because some cases can arise from highly unusual disorders such as a cervical vertebral fracture (see p. 332) or a serious internal neoplasm. In some cases even rectal examination, ultrasonographic examinations, or radiography (conventional or computed tomography) may be justified.

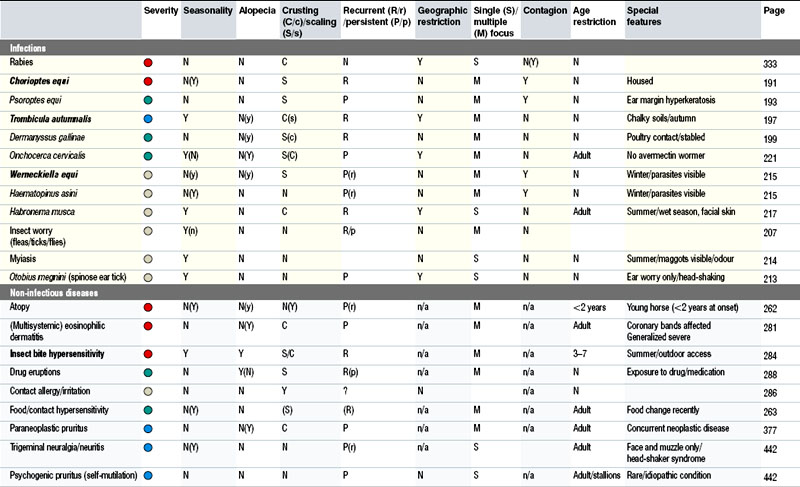

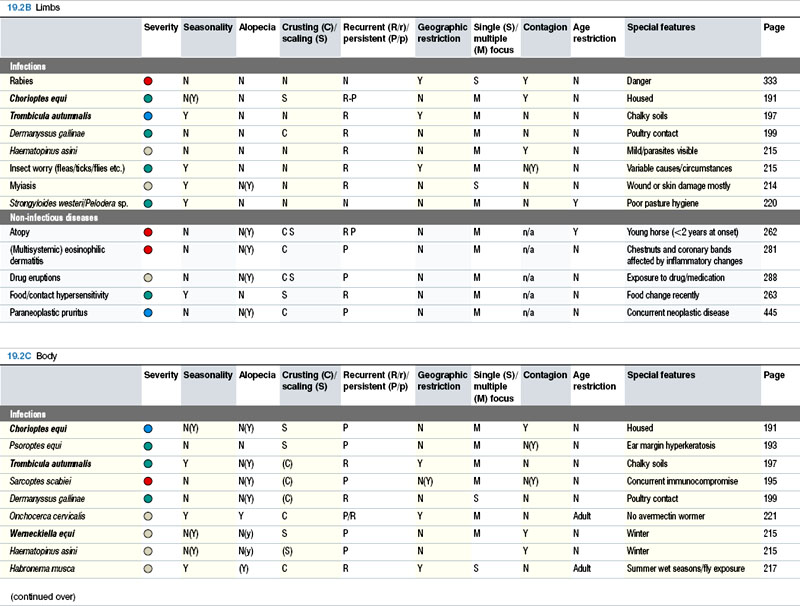

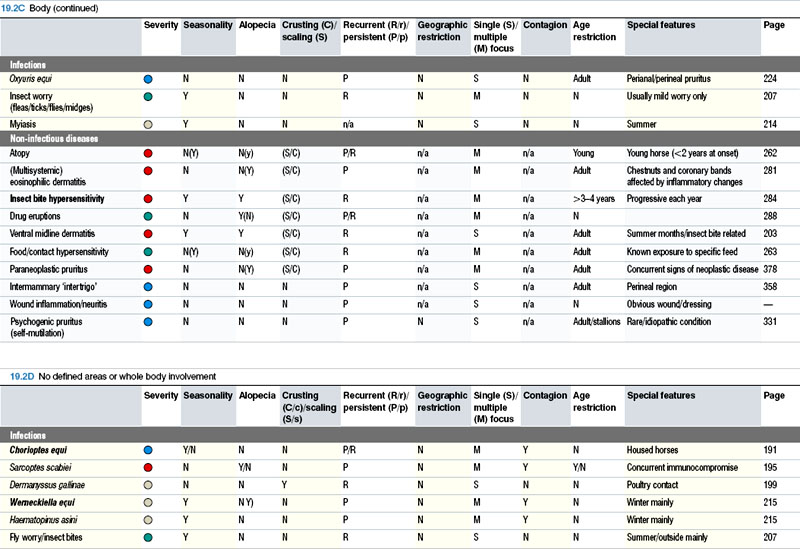

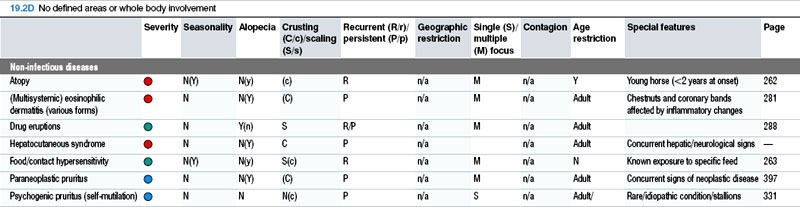

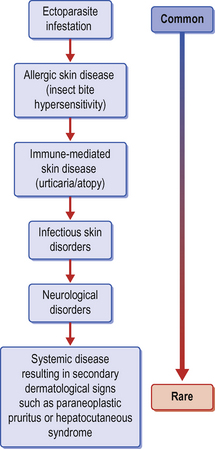

A good working knowledge of the main and less common disorders associated with pruritus can help enormously. Table 19.2 and Fig. 19.3 outline the main diagnostic possibilities for the pruritic horse; there will, however, inevitably be some rare conditions that are not shown here.

Alterations in hair quality and quantity (hair follicle disorders and alopecia)

Alopecia is defined as the absolute loss of hairs or the reduction in hair length or diameter when the number of hairs per unit areas may be normal (Fig. 19.4). Alopecia can be congenital (and sometimes also hereditary), when it is termed hypotrichosis, or acquired. The name alopecia does not apply to the simple rubbing away of hairs to the extent of an apparently bald patch such as occurs when rugs or other tack/harness rub hairs away. In these cases the skin is normal and the hairs are themselves normal in number, density and quality (Fig. 19.5).

Congenital hypotrichosis is very rare in horses but it does occur – of course there are some disorders that are hereditary and congenital where the alopecia becomes evident at a later age. There are some circumstances such as neonatal hypothyroidism and prematurity when an apparent hypotrichosis/alopecia can be detected at birth but although these are therefore congenital they have no genetic foundation and are classified as acquired congenital disorders. Perhaps the best example of a true hereditary/genetic alopecia is the relatively common mane and tail dystrophy of the Appaloosa horse (see p. 245). Another syndrome of adult-onset facial hypotrichosis (often to the extent of complete hair loss) is recognized by clinicians but is poorly described (Fig. CD19 • 1A and B) . There is no known aetiology and biopsies of the skin simply identify atrophic non-functional follicles.

. There is no known aetiology and biopsies of the skin simply identify atrophic non-functional follicles.

Loss of hair without any other accompanying clinical signs such as pruritus, scaling, crusting, erosion or ulceration occurs in relatively few conditions (see Fig. 11.33). However, as these other clinical signs very frequently occur with loss of hair, they should always be considered as part of the hair loss syndrome. Acquired forms of alopecia have been divided into two groups depending on the cause and whether the hair will grow back once the condition has resolved (Stannard 2000):

Cicatricial alopecia

results when the hair follicles are completely destroyed by a pathological process such as physical, chemical or thermal injuries, infections or tumours and results in a complete and permanent alopecia. A typical example is a scar from a wound or chemical burn (Fig. 19.6 and Fig. CD19 • 2) . This same effect is sometimes used to create identification marks on horses using thermal branding. The resulting alopecia and scarring enables firm identification to take place (Fig. 19.7 and Fig. CD19 • 3

. This same effect is sometimes used to create identification marks on horses using thermal branding. The resulting alopecia and scarring enables firm identification to take place (Fig. 19.7 and Fig. CD19 • 3 ; see also Fig. 16.1A).

; see also Fig. 16.1A).

Severe viral (see p. 129) or bacterial skin infections (see p. 141) and some tumour conditions such as the equine sarcoid (see p. 387) also cause localized alopecia in which there is seldom any recovery of hair growth.

In non-cicatricial alopecia

1. Traumatic injuries that result in epidermal and/or superficial dermal damage (as a result of either direct trauma, chemical or thermal injuries or self-inflicted trauma including the effects of pruritus and cutaneous ‘worry’). Even pressure applied to the skin under bandages, etc. can cause significant hair loss – sometimes with more overt epidermal or dermal damage but sometimes without these. Often there is a dramatic shedding of hair as a result of contact with urine, diarrhoeic faeces, saliva, wound exudate, etc.) (see p. 299).

2. Alterations in the function of hair follicles including several dystrophic conditions that incorporate the dramatic effluvium or gross shedding of hairs at defined stages in the growth cycle (see p. 346). Alopecia areata is also a good example of a sterile folliculitis resulting in localized or sometimes generalized alopecia (see p. 278).

3. Bacterial and fungal infections resulting in hair follicle suppression or hair shaft damage are important causes of alopecia – dermatophilosis, staphylococcal and streptococcal dermatitis and dermatophytosis are good examples of this type of response.

Abnormally long/dense hair coat

The hair coat quality and quantity varies widely between breeds and individuals. Most horses have a ‘typical’ pattern of hair growth with isolated whorls and increases and reductions in coat density at different sites. For example, the hair density on the side of the face is usually much less and the hairs are much shorter here than on the main body. Some horses have ‘unusual’ patterning of hair growth that can at first glance be misinterpreted as an abnormality. A good example is shown in Fig. 19.8, in which the lie of the hair creates an impression of abnormality. A brief examination will show that this is a normal healthy coat that has been present from birth. This is a relatively common occurrence but is very variable in extent.

There are individual horses that have hair length variations and some breeds that have longer hair coats than others. Some have isolated ‘tresses’ of longer hair in summer and these same sites usually have a normal length winter coat but sometimes a summer coat hair growth can be identified at these sites (Fig. 19.9).

There are also some individuals that may have a very dense wavy, curly coat in winter and more normal hair coat in summer – the important point about all these animals is that they shed normally and usually have shown the same pattern of hair growth throughout their lives without any concurrent primary or secondary pathology. An interesting ‘curly coat’ genetic variation is being encouraged by some breed societies (see p. 233).

For all practical purposes the only disease that is characterized by acquired generalized hirsutism (overgrowth of hair) is pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) (pituitary adenoma/equine Cushing’s disease) (see p. 322). This symptom is almost pathognomonic for the disease in older horses and occurs in a high proportion of cases.

Investigation of equine skin with either altered density or length of hair

As is usually the case, a full history will be very helpful. Indeed, in most of the major syndromes much of the differential diagnosis can be achieved directly from this. The full range of possible aetiological states also exists for cases showing hair loss and alteration in hair density and structure so it is in fact always wise to explore the history to the fullest possible extent. For example, diagnosis of a genetically based disorder occurring in a known specific breed, such as the mane and tail dystrophy condition in Appaloosa horses, can usually be assumed from the history and the physical appearance (Fig. 19.10). Of course such intuitive supposition can also be misleading. The loss of mane and tail hairs may simply be a matter of hair pulling by either another horse or even cattle (see Fig. 19.10A). Chronic ingestion of selenium (either in inorganic feed-supplement form, or in seleniferous plants and grains) may result in significant more-or-less symmetrical alopecia and hoof wall growth alterations (see Fig. 12.11). If the history includes dietary supplementation or the environmental conditions suggest that plant feeds might be involved, the process of diagnosis can be shortened dramatically. This also emphasizes the importance of understanding the local environmental conditions – are potentially toxic plants prevalent in the area and available to the horse? Has the horse received any abnormal nutrients? It is possible to draw effective diagnostic conclusions from the historical features and clinical appearance alone in most cases.

Having completed the history, a full clinical examination is important. The objective is to try to establish whether the hair loss is primary (true alopecia) or secondary (false alopecia). Skin rubbing by tack or harness or contact with walls and other solid objects can induce changes that closely resemble alopecia. Viewing the skin with an illuminated magnifying glass can usually confirm the nature of the problem. Furthermore, the correlation of the hair loss with obvious trauma is a key factor. Careful questioning can be very helpful (Table 19.3).

Table 19.3 Possible questions for the investigation of hair loss in horses

= very mild

= very mild = mild

= mild = moderate

= moderate = severe

= severe