Chapter 23 Surgery of the Swine Reproductive System and Urinary Tract

Male

CASTRATION OF OLDER PIGS

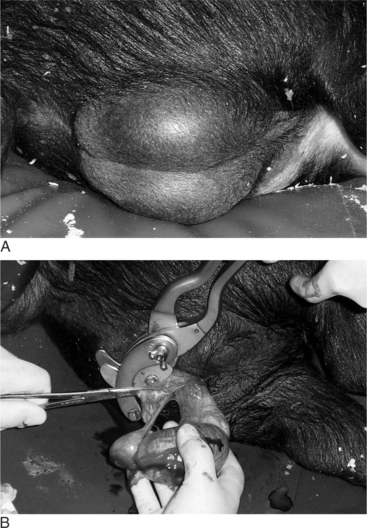

Veterinarians may be asked to castrate older pigs intended for show or mature boars that will no longer be used for breeding. Castration of older pigs is best performed with the pig sedated or under general anesthesia. The boar is restrained in lateral recumbency, and the surgical site is aseptically prepared (Figure 23-1A). A 4- to 6-cm incision is made overlying the testis at the ventral aspect of the scrotum. The testis should be removed with the vaginal tunic intact (Figure 23-1B). Inguinal fat and soft tissue are stripped from the spermatic cord and evaluated for the presence of an inguinal hernia. The vaginal tunic and spermatic cord are twisted until the cord is tightly compressed to the level of the external inguinal ring (see Figure 23-6). Two circumferential ligatures (No. 1 synthetic absorbable suture material) are placed around the vaginal tunic and spermatic cord. An emasculator (see Figure 4.4-8A and B) is used to complete the castration (see Figure 23-1B). Closure of the surgical wound is rarely done and should only be performed if asepsis has been maintained. We prefer to administer antibiotics for 3 days, beginning the day of surgery, to reduce the incidence of postoperative infection. Also, the animal should be kept in a clean, dry stall during this period.

UNILATERAL CASTRATION

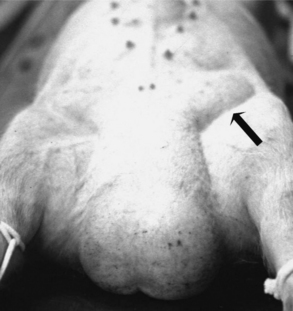

Indications for removing only one testis include testicular trauma, torsion (Figure 23-2), hematoma (Figure 23-3), seroma, and orchitis or periorchitis. The damaged testis may cause enough swelling, heat, and pressure to reduce fertility. The boar is placed under general anesthesia, a 6-cm incision is made over the testis starting at the most ventral aspect of the scrotum, and the testis is removed by circumferential ligation and excision. The wound should be left open for drainage and second intention healing. Antibiotics are administered for 5 to 7 days, and daily hydrotherapy is used to minimize postoperative swelling. Affected boars may return to productive service 30 to 60 days after surgery.

Figure 23-2 Boar with testicular torsion. Note swollen hemorrhagic testis.

(Courtesy of Dr. Andre Desrochers; University of Montreal.)

INGUINAL HERNIA

Inguinal hernia results when a defect permits intestines or other abdominal organs to pass into the inguinal canal. The hernia develops when an abnormally large and patent vaginal ring allows free communication between the vaginal tunic and peritoneal cavities. Organs protrude into the scrotum to form a scrotal hernia, a more exaggerated form of the defect (Figure 23-4). These hernias are common in swine. The frequency of inguinal hernia among the porcine population varied between 0% and 15.7%, with a realistic estimate of approximately 1%. The development of these hernias seems to be genetically influenced. One study indicated that the variation associated with anatomic structures relevant to scrotal hernia is influenced polygenically. In that study, the heritabilities of susceptibility to scrotal hernia development were estimated to be 0.29, 0.34, and 0.34 in Duroc, Landrance, and Yorkshire-sired pig groups, respectively. Inguinal (see Figure 23-4) and scrotal hernias need to be differentiated from hydrocele, scirrhous cord, and hematoma (see Figure 23-3) of the testis. Diagnosis is made by historical data (e.g., a pig that has been castrated before is more likely to have a scirrhous cord) and direct manipulation. If necessary, ultrasonography and needle aspiration can be used. Inguinal hernias often are encountered at the time of castration. Some of these hernias will reduce spontaneously but recur later. With chronic inguinal hernia, intestinal incarceration and strangulation may be observed.

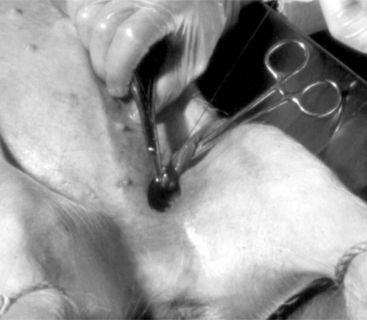

Surgical repair of an inguinal or scrotal hernia is easier before the pig is castrated. With the pig restrained in dorsal recumbency and its rear quarters elevated, the inguinal and scrotal area is thoroughly cleaned and prepared for surgery. An oblique incision is made over the affected superficial inguinal ring (Figure 23-5). Once the incision pierces the skin, the subcutaneous tissue is dissected bluntly. The tunica vaginalis is also isolated by blunt dissection (see Figure 23-5). The tunica vaginalis should be kept intact, because this will keep the intestine contained. While external pressure is put on the scrotum, the tunics are gently pulled free from their scrotal attachment. The tunic and testis are then twisted to force the intestines into the peritoneal cavity (Figure 23-6). The tunics and spermatic cord are transfixated as close to the superficial inguinal ring as possible. The tunic and cord are cut, and the superficial inguinal ring is closed with interrupted or horizontal mattress sutures. The herniorrhaphy site is checked by applying external pressure on the abdomen. The skin is closed using absorbable sutures. The authors recommend checking the opposite inguinal ring for possible bilateral herniation before performing a castration. If the surgery was done to repair a large hernia in which marked serum accumulation in the scrotum is expected, an incision in the most ventral aspect of the scrotum should be performed to provide ventral drainage. If intestinal adhesion and incarceration are observed during surgical correction, the vaginal tunic should be opened and the intestine dissected free or an intestinal resection and end-to-end anastomosis performed. If an inguinal hernia occurs after castration, one needs to clean and lavage the herniated bowel, enlarge the vaginal and superficial inguinal ring, and replace the prolapsed intestine (if it is judged still viable) before suturing the superficial inguinal ring closed.

PREPARATION OF TEASER BOARS

Vasectomy or epididymectomy is done to produce teaser boars—which are used to detect sows in heat for artificial insemination or breeding to valuable boars—or to promote onset of cyclicity in confined gilts (young females). For vasectomy, the boar is placed in dorsal recumbency under general anesthesia, and a 4-cm incision is made over each spermatic cord approximately 6 cm cranial to the ventral aspect of the scrotum. Each spermatic cord is elevated and incised, and the ductus deferens isolated. The ductus deferens is firm and pale, and an arterial pulse is not present (see Figure 19.1-10). A 3- to 4-cm segment of the ductus deferens is excised and each end ligated. The incision through the tunic is sutured with No. 2-0 PDS synthetic absorbable suture material, and the skin is sutured with No. 0 nonabsorbable suture material in a simple interrupted pattern. Epididymectomy is done by making a 2-cm incision in the scrotum overlying the tail of the epididymis. The tail and 1 cm of the body of the epididymis is isolated. Ligatures are placed between the testis and the tail of the epididymis and around the exposed portion of the body of the epididymis. The epididymis is excised between these two ligatures. The skin is closed with No. 0 nonabsorbable sutures in an interrupted pattern.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree