Chapter 21 Surgery of the Swine Digestive System*

Swine industry economics often limits veterinarians’ options for surgical management of disease. The main task is to relate production unit economics and disease control to increase profits. Veterinarian services should meet enterprise needs because the individual pig versus the population in large-scale operations often has a minimal value. Surgery on an individual pig is not always cost-effective. However, some conditions—like hernia, prolapse, dystocia, and atresia—that can occur in large numbers of animals can be very costly and need to be investigated so a solution and treatment can be applied. In a commercial swine operation, the veterinarian often teaches the manager and experienced personnel how to perform minor surgical procedures, including castration, ear notching, canine teeth clipping, and tail amputation in a cost-effective fashion. The veterinarian’s role is to ensure these procedures are properly and humanely performed. Among purebreds, pets (such as Vietnamese potbelly pigs), or biomedical research animal model pigs, the individual animal often has a high perceived value, and surgery is often requested. Also, genetically valuable breeding stock allow for more sophisticated treatment of disease. A veterinarian who offers excellent surgical service to swine producers will have greater credibility as a herd consultant.

Digestive tract

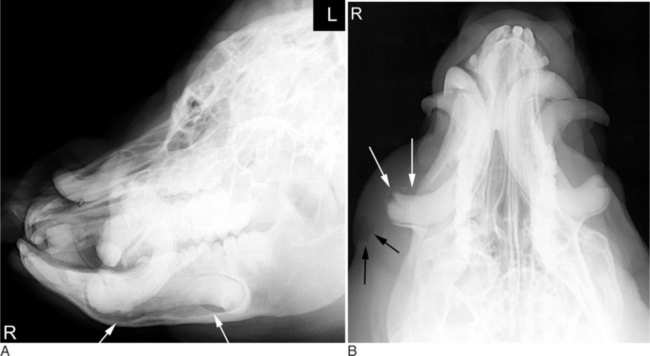

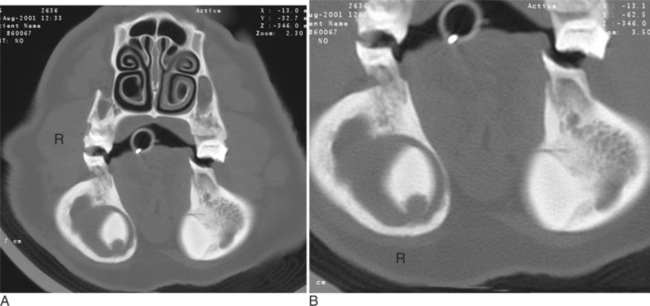

Infected mandibular canine teeth (tusks) result in local swelling and purulent drainage. The local swelling along the mandible is difficult to detect on physical examination because of the normally thick jaw of pigs. Purulent drainage can be seen at the lateral aspect of the mandible, generally over the caudal aspect of the tooth root. Some animals have decreased appetite and drooling of saliva from the affected side. Halitosis can be a feature if the infected tooth is draining into the oral cavity. The diagnosis is confirmed by radiography under general anesthesia or heavy sedation. On radiography, one can document the soft tissue swelling and areas of lysis surrounding the affected canine tooth (Figure 21-1A and B.) CT examination is more precise and allows confirmation of osteitis surrounding the infected tusk (Figures 21-2 and 21-3A and B.)

Treatment of an infected tooth requires removal. However, this is a difficult surgery and should only be undertaken if one can definitively confirm the diagnosis. The owners should be warned of the possibility of mandibular fracture, and appropriate equipment should be ready if repair is necessary. After induction of general anesthesia, the animal is placed in sternal recumbency. Lateral recumbency can also be used. To give access to the crown of the affected tooth, a mouth gag (block of wood or a canine mouth gag) (Figure 21-4) is placed between the contralateral cheek teeth. A dental elevator is placed around the crown as far caudal as possible to separate the tooth from the alveolus. A second approach is made over the most caudal aspect of the root as follows. First, a 3- to 4-cm vertical incision is made over the most caudal aspect of the affected tooth. Electrocautery is helpful in providing hemostasis. A Gelpi retractor is placed, and the incision is bluntly extended to the root. A dental elevator is used to free the root circumferentially as far rostrally as possible. Using a mallet and 1-cm tooth punch, the veterinarian gently taps the tooth while the assistant applies traction on the crown. The tooth’s comma shape necessitates moving it in a semicircle for extraction (Figure 21-5). The extraction is difficult, and repulsion and traction must be applied in the correct direction to minimize the possibility of mandibular fracture. If the tooth was draining caudally, the incision is left open to heal by second intention. If no drainage is present caudally, the incision can be closed in two layers with absorbable suture material, preferably monofilament.

Postoperatively, antimicrobials are continued for 2 weeks, and the draining tracts are kept clean with warm water and dilute Betadine solution. Vitamin A and D ointment is placed around the draining tract to prevent scalding.

If a mandibular fracture occurs, the latter is fixed with wires placed in a figure-eight pattern around the crown of teeth adjacent to the fracture site (see Chapter 10 for further details.) These wires will need to be removed 2 to 4 months later.