Chapter 19 Surgery of the Sheep and Goat Reproductive System and Urinary Tract

19.1 Anesthesia and Restraint

Most elective surgeries in small ruminants can be done by using a combination of chemical and physical restraint. In nonemergency situations (e.g., teaser preparation in rams and bucks, laparoscopy), food should be withheld for 24 to 48 hours and water for 12 to 24 hours. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given 2 hours before surgery. Mild sedation can be obtained with 0.05 mg/kg xylazine. Chemical restraints most commonly used include a combination of xylazine, telazol, and ketamine. A xylazine (0.11 mg/kg) and telazol (13.2 mg/kg) IV combination provides 90 to 120 minutes of anesthesia with good smooth muscle relaxation. Telazol (6.6 mg/kg IV) and ketamine (6.6 mg/kg) IV provide 20 to 40 minutes. Telazol (6.6 mg/kg), ketamine (6.6 mg/kg), and xylazine (0.11 mg/kg) IV provide 60 to 90 minutes of anesthesia time.

Surgery of the Female Reproductive Tract

CESAREAN SECTION

Cesarean section should be considered to manage dystocia when vaginal delivery is not possible (oversized fetus or failure of cervical dilation “ring womb”). Occasionally the technique can be used to terminate pregnancy in ewes that are suffering from pregnancy toxemia or ketosis.

VENTRAL ABDOMINAL PARAMEDIAN APPROACH

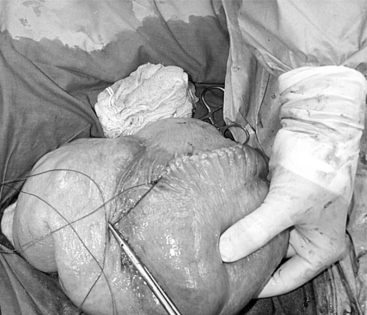

The 25-cm skin incision extends from the base of the udder toward the umbilicus. The incision should be made between the linea alba and subcutaneous abdominal vein, which is very prominent in late pregnancy. The approach is continued by using a combination of blunt and sharp dissection through subcutaneous tissues. The external rectus abdominis sheath is sharply incised, the rectus muscle bluntly separated along its fibers, and the internal rectus sheath tented, along with the peritoneum, and incised. The abdominal incision may be extended, if necessary, to allow easy exteriorization of the uterine horn. The operator should be careful not to incise the greater omentum, which lies deep into the peritoneum. The greater omentum and abdominal viscera are retracted cranially to expose the uterus. The uterine horn is grasped and exteriorized gently to avoid perforation (Figure 19.1-1). Hysterotomy is performed on the greater curvature of the uterine horn, starting at the upper third and extending towards the uterine bifurcation. Care should be taken to avoid incising through cotyledons, which prevents excessive bleeding. In most cases, ewes carry more than one fetus. Therefore a uterine incision large enough to allow a fetus in the other horn to be exteriorized through the same incision should be placed along the caudal aspect of the horn. If this is too difficult, a second hysterotomy may be performed on the other uterine horn. Depending upon the presentation, the fetuses are exteriorized by traction on the front legs and head or on the hind legs. During exteriorization of the fetus, the surgeon should be careful not to tear the uterine wall. Excess fetal fluid should be removed from the uterus. The placenta should be removed only if it is already detached. The uterus is sutured with an atraumatic needle with chromic catgut (No. 0 or 1-0) or similar synthetic absorbable suture in a continuous inverting suture pattern (Figure 19.1-2). If the uterus is compromised, a two-layer closure may be indicated. The sutured uterus should be checked for tears and lavaged copiously with sterile fluids before it is replaced into the abdominal cavity. Some authors suggest intrauterine and intraabdominal antibiotic therapy, but this is not usually necessary if the surgery is performed under aseptic or very clean conditions and systemic antibiotics are provided.

Ventral Midline Approach

The ventral midline approach to cesarean section in small ruminants differs from the paramedian approach in that the skin and abdominal incisions are made directly over the linea alba. Incision of the skin starts at the base of the udder and is extended about 20 cm cranially towards the umbilicus. The subcutaneous tissue is incised to expose the linea alba, which should be evident as a small concave line. The abdominal wall is grasped with tissue forceps and tented, and a small incision is made on the linea alba (Figure 19.1-3). The incision is continued through the linea alba and peritoneum, with scissors guided by the operator’s index and middle fingers to avoid damaging the omentum or intestinal loops. Exteriorization of the uterus and delivery of fetuses is done in the same manner as described for the paramedian approach. The linea alba and peritoneum are sutured in an interrupted or continuous pattern with synthetic absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures (again, the choice is surgeon’s preference). Subcutaneous tissues and skin are closed routinely. Postsurgical care is similar to the paramedian technique.

OVARIECTOMY AND OVARIOHYSTERECTOMY

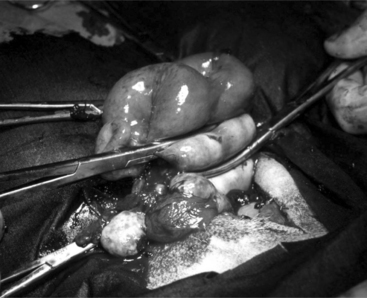

An ovariectomy or ovariohysterectomy performed as an elective surgery should be done during the luteal phase of the cycle or during anoestrus so that the uterus is relaxed and bleeding problems that would be associated with a toned, well-vascularized uterus during estrus are prevented. Ovariectomy is easily performed on the anesthetized animal placed in dorsal recumbency. A small 6- to 8-cm incision is made in the ventral midline just cranial to the udder and continued into the abdominal cavity as described for cesarean section. The surgeon introduces two fingers into the abdominal cavity. The urinary bladder is identified, and the uterus is recognized in its dorsal aspect by following one of the horns to the uterine bifurcation. Once the uterine horn is grasped between the fingers, it is pulled towards the surgical incision. Both horns are exteriorized by gentle traction (Figure 19.1-4).

For hysterectomy or ovariohysterectomy, the mesometrium and round ligament of each uterine horn are transected after ligation of small blood vessels. Transfixation ligatures are placed proximal to the cervix; the surgeon should make sure to include the large uterine vessels located on each side. The uterus is transected at the level of the body between two hemostatic forceps (Figure 19.1-5). A circumferential transfixation ligature of absorbable suture material is placed close to the cervix. If the remaining portion of the uterine body is large, it should be closed with an inverting suture pattern before replacing it in the abdomen. Removal of one horn or part of a uterine horn, a partial hysterectomy, is sometimes used in reproductive experimentation or for pathology confined to one side of the abdomen. The technique is similar to a total hysterectomy, although a flank approach would be possible. The vasculature supplying the ovary and horn on one side are ligated and transected. The remaining uterus is closed with an inverting pattern. Some advocate a two-layer uterine closure. For successful reproductive performance, it is essential the remaining ovary and uterine horn are normal.

Laparoscopy

An area 25 cm by 25 cm cranial to the mammary gland is prepared by clipping and surgical scrubbing. For most reproductive procedures, two or three portals are necessary: one each for the laparoscope, a manipulation instrument, and special instruments (insemination gun, suture material) (Figure 19.1-6). For insemination and embryo transfer, only two portals are necessary: one each for the laparoscope and insemination gun. The site of the desired portals is infiltrated with local anesthetic before introducing a trocar and cannula. For simple techniques, the portals are created by making a small skin incision to allow trocar introduction. The trocar is advanced 4 cm subcutaneously before the abdominal cavity is penetrated by applying pressure on the abdominal wall muscle and peritoneum. This provides portals into the abdomen not directly aligned with the skin incision, which helps to prevent contamination of the abdominal cavity. This technique does not require suturing the abdominal muscle. Visualizing the abdominal viscera requires insufflation with CO2 and elevating the hindquarters to a 40° angle.

Figure 19.1-6 Laparoscopic artifical insemination: location of the portals for the light source (left) and insemination gun (right).

Surgery of the Male Reproductive Tract

CASTRATION

Young animals are usually sedated and restrained in a sitting position with the legs on the same side held together. The bottom third of the scrotal sac is excised, and the testes are removed by stripping while maintaining pressure on the inguinal ring (Figure 19.1-7).

Figure 19.1-7 Castration in a billy goat. The bottom third of the scrotum has been resected and the testes are stripped.

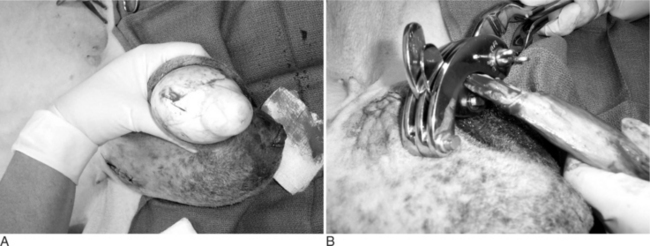

In the adult ram or buck, general anesthesia is recommended. The animal is placed either in lateral or dorsal recumbency. The scrotum and surrounding area are clipped and prepared for surgery. An incision is made on the lateral surface of the testis through the skin and tunica dartos. The testis and its envelopes are separated by blunt dissection. The vaginal tunic is excised to expose the testis. The cremaster muscle is separated from the vascular testicular cord. Each of these structures is ligated by transfixation suture. Some practitioners prefer to ligate the spermatic artery and vein separately. The cord is transected distal to the ligatures. Use of an emasculator can be indicated if the testes are normal size (Figure 19.1-8, A and B). The vaginal tunic is transected distally enough to allow the tunics to be closed over the remaining cord. An inverting suture pattern is used with an absorbable suture material. The tunica dartos muscle is closed over the wound with a simple continuous pattern. Excess skin may be trimmed. The subcutaneous tissues and longitudinal skin incision are closed. Bandaging the scrotum is recommended if bleeding is observed. Alternatively the incisions can be left to close by second intention if preferable or if the conditions are unsanitary.

VASECTOMY

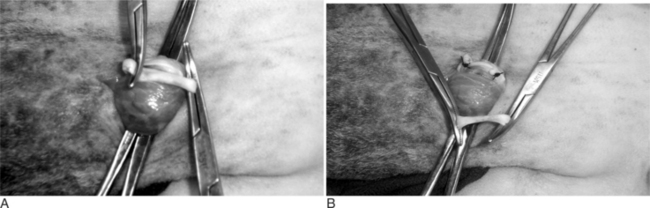

The scrotal skin is prepared by clipping and surgical scrubbing. Surgical drapes are placed around and underneath the scrotum. A 3- to 4-cm vertical incision is made slightly medial on the cranial surface of the scrotal skin above the testicular cord. The spermatic cord is freed by blunt dissection and exteriorized with the help of hemostatic forceps (Figure 19.1-9). The vas deferens can be easily identified by palpation or visually by its white color and the presence of adjacent vein and artery. The vas deferens is exteriorized by using forceps or a spay hook through a small nick made in the vaginal tunic. A 3-cm portion of the vas deferens is removed after ligating each end (Figure 19.1-10, A and B). The vaginal tunic does not need to be sutured. The skin is sutured or stapled, and the same procedure is repeated on the other side. Excised tissue should be submitted for histological confirmation. Flushing and observing spermatozoa under the microscope is another quick way to confirm the excised tissue was in fact the vas deferens.

Figure 19.1-9 Vasectomy in a ram: exteriorization of the spermatic cord and identification of the vas deferens.

EPIDIDYMECTOMY

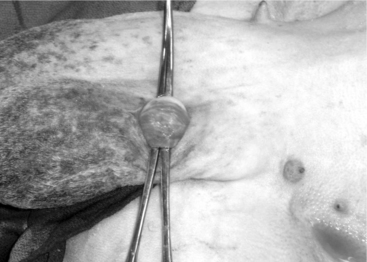

The animal is prepared as for castration. A local block is provided by infusing 2% lidocaine in the ventral scrotal skin directly over the caudal epididymis. The testis should be held firmly within the scrotum to better visualize the prominent tail of the epididymis (Figure 19.1-11). The skin is incised (2.5 to 3 cm) on the ventral, posterior aspect of the scrotum (just above the caudal epididymis). Using blunt dissection, the veterinarian isolates the epididymis and holds it with an instrument or stay suture. The tail of the epididymis is transected after ligating each border with a nonabsorbable suture material. The skin is sutured by using a simple interrupted suture pattern. Semen should be collected at least three times before the male is used as a teaser.

TRANSLOCATION OF THE PENIS

The objective of this surgery is to translocate the preputial opening laterally to render vaginal intromis-sion of the penis impossible during normal erection and mounting behavior. It is preferable to perform penile deviation under general anesthesia or deep sedation/analgesia. The animal is placed in dorsal recumbency, and the area from the umbilicus to the base of the scrotum is clipped, scrubbed, and draped for surgery. Special attention should be given to thoroughly flushing the prepuce with diluted iodophor. A skin incision is made about 1.5 to 2 cm around the preputial orifice and continued caudally towards the sigmoid flexure (Figure 19.1-12). The prepuce is entirely freed from the skin and surrounding tissue with blunt scissors dissection. Placing a catheter in the prepuce helps orient the surgeon. Once the desired length of the prepuce is completely freed, a site is selected on the abdominal wall at a 45° angle from the base of the penis to create the new preputial location. A circular skin flap is removed at this site (Figure 19.1-13). A closed long forceps is used to create a subcutaneous tunnel that extends from the circular skin incision to the base of the scrotum. The freed prepuce is placed in a sterile plastic sleeve, grasped with the forceps, inserted into the subcutaneous tunnel, and transferred to the new location. The surgeon must be sure that the organ does not twist. The preputial opening is sutured to the skin with synthetic nonabsorbable suture material in an interrupted simple or horizontal mattress pattern. The midline abdominal skin incision is closed routinely (Figure 19.1-14). Postoperative care includes systemic antibiotics. Ventral edema may develop in some animals and persist, generally for a few days. Urination should be verified, and the patient should be examined carefully if there is a large amount of persistent preputial edema. Skin sutures may be removed 10-to-14 days after surgery.

Figure 19.1-12 Translocation of the penis: skin incision around the preputial orifice continuing caudal towards the sigmoid flexure.

Figure 19.1-13 Translocation of the penis: removal of a circular flap of skin at the site where the preputial opening is to be relocated.

Boundy T, Cox J. Vasectomy in the ram. Practice. 1996;18:330-334.

Harrison FALaparotomy and hysterotomy. Surgical techniques in experimental farm animals, ed 1. Oxford University Press; New York; 1995

Janett F, Hussy D, Lischer C, Hassig M, Thun R. Semen characteristics after vasectomy in the ram. Theriogenology. 2001;56:485-491.

Mobini S, Heath AM, Pugh DG. Theriogenology of sheep and goats. In: Pugh D, editor. Sheep and goat medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2002.

Riddle MG. Castration of the normal male. In Wolfe DF, Moll HD, editors: Large animal urogenital surgery, ed 3, Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins, 1999.

Riddle MG, Wolf DF. Embryo transfer. In Wolfe DF, Moll HD, editors: Large animal urogenital surgery, ed 3, Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins, 1999.

Smith M, Sherman DReproductive system. Goat medicine and surgery, ed 1. Lea and Febiger; Baltimore; 1994

Williams CSF. Routine sheep and goat procedures. The veterinary clinics of North America: food animal practice. 1990;6:737-758.

Wolfe DF. Surgical preparation of estrus detector males. In Wolfe DF, Moll HD, editors: Large animal urogenital surgery, ed 3, Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins, 1999.

19.2 Urolithiasis

Urinary calculi, or uroliths, cause disease in ruminants through trauma to the urinary tract and obstruction of urine egress. Calculi are mineral/mucoprotein aggregates that may be a single or multiple mass(es) that measures several millimeters in diameter or numerous fine, sandlike particles that pack together to fill the urethral lumen.

Preoperative Considerations

If an animal is to be culled, slaughter should be delayed for 4 to 6 weeks after surgery for animals that are suffering from bladder or urethral rupture. This delay allows debilitation and uremia to pass and provides ample time for healing of tissues damaged by urine. In cases of urethral rupture, small stab incisions into the skin of swollen areas around the perineum, prepuce, and ventral abdomen may facilitate urine drainage. A sterile instrument can be inserted into the stab incisions to gently spread the skin apart, thereby opening fascial planes for better drainage of extravasated urine.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree