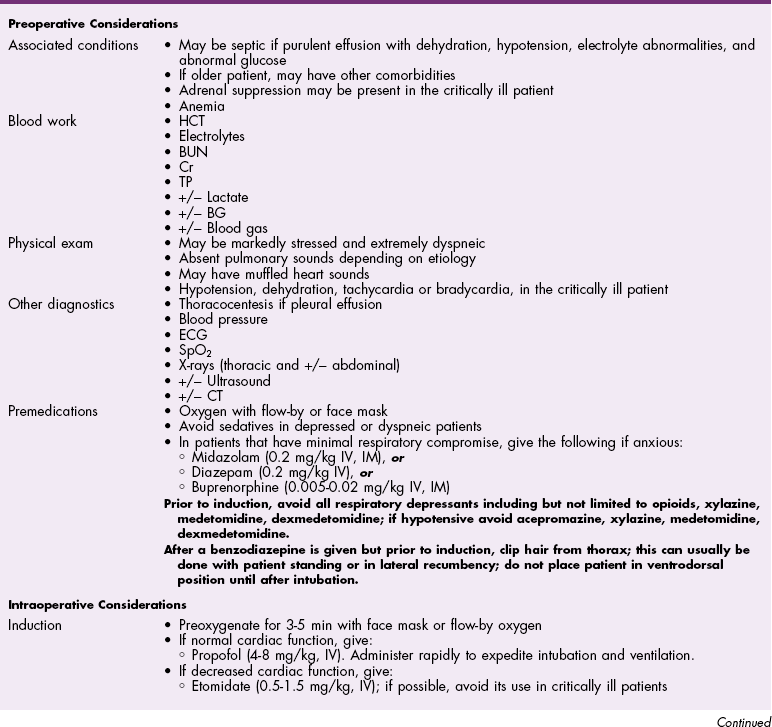

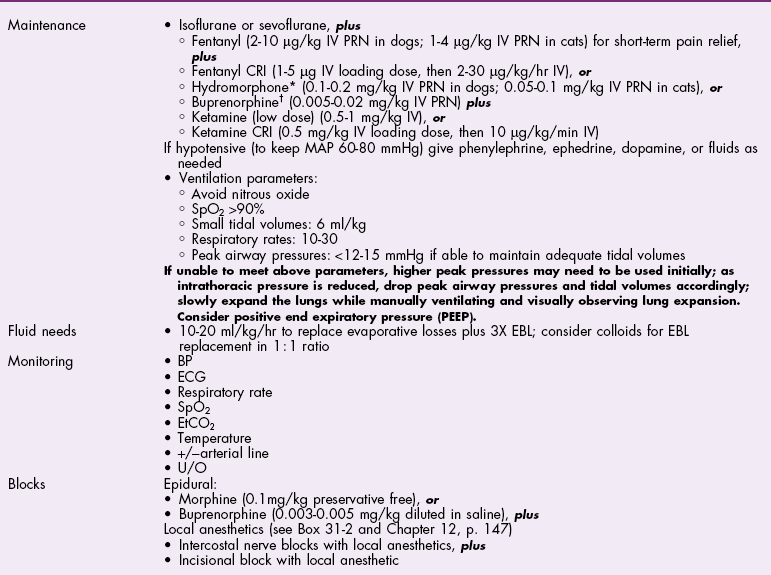

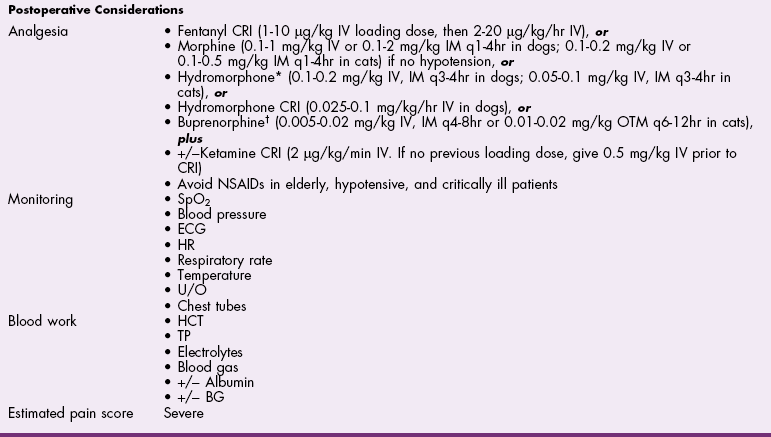

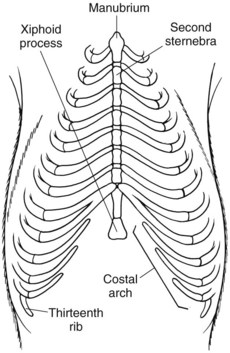

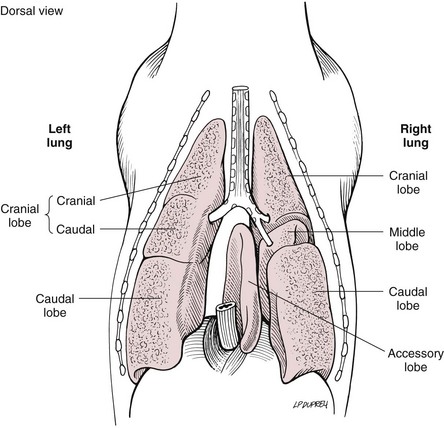

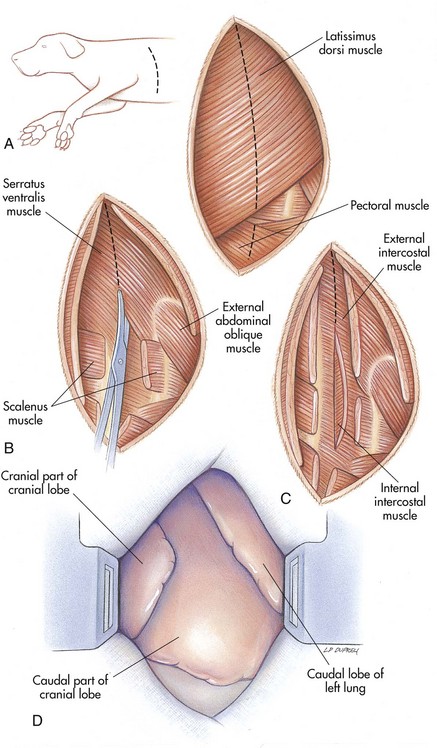

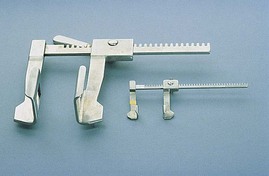

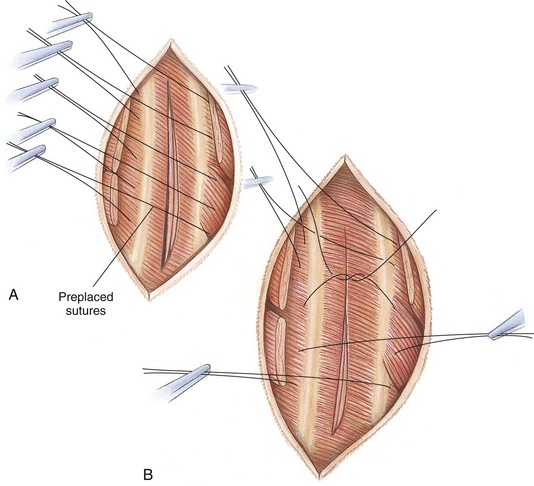

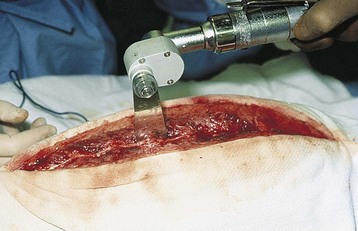

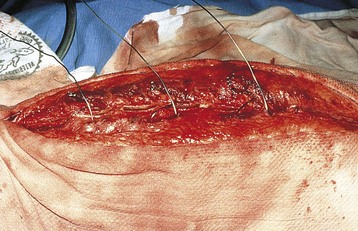

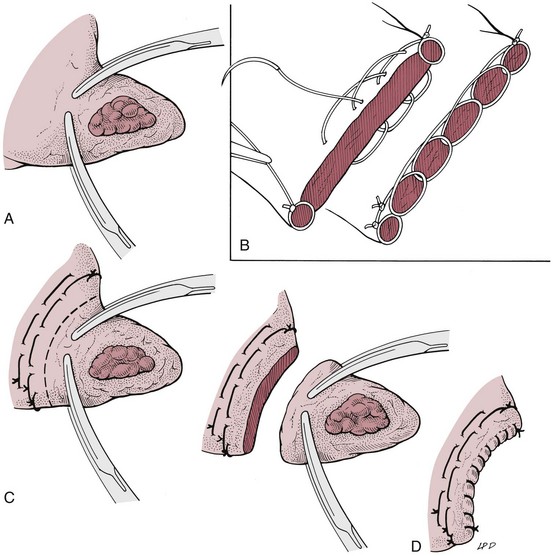

Chapter 30 General Principles and Techniques Animals with traumatic lesions that impair respiration (e.g., flail chest) or those with acute respiratory impairment (i.e., ruptured bulla or ruptured pulmonary abscess) often require emergency stabilization (e.g., stabilization of rib segments, thoracentesis, and oxygen therapy) before surgery. Equipment for thoracentesis and chest tube placement should be readily available, and clinicians should be familiar with these techniques (see pp. 996-997). The thorax is one of the most common regions injured following blunt trauma; thoracic injuries were identified in over 72% of patients in a recent study (Simpson et al, 2009). Concurrent abdominal and chest injuries were found in 50% of injured animals. With large neoplastic lesions, positioning the animal in sternal recumbency or in lateral recumbency with the affected side down and providing oxygen (i.e., nasal insufflation or oxygen cage) often is beneficial. Blood gas analysis or evaluation with pulse oximetry is warranted preoperatively in patients undergoing thoracic surgery to detect and define the severity of respiratory impairment. Unexplained abnormalities should be investigated because ventilatory impairment caused by nonsurgically correctable disease (i.e., diffuse micrometastasis) occasionally is identified. If possible, significant anemia should be corrected before surgery (see p. 84). Respiratory patients should be managed with extreme care until intubation has been accomplished and ventilation can be assisted. Premedication with any drug that causes hypoventilation is contraindicated (see Table 31-3 on p. 994). Additionally, every attempt should be made to minimize stress to the patient prior to induction. Oxygen support, even while placing an intravenous catheter, may be necessary. Pulse oximetry with a sensor that can be secured to the tail can be especially helpful with perioperative monitoring of patients in respiratory distress. Prior to induction, the anesthesia provider should be prepared with airway devices, anesthesia machine, monitors, as well as induction and emergency drugs. Preoxygenating the patient for 3 to 5 minutes prior to induction (see p. 992) should be followed with a rapid induction and intubation. Intubation of a bronchus rather than the trachea may be disastrous in compromised animals; therefore, both sides of the chest cavity should be auscultated and the endotracheal tube palpated in the thoracic inlet to ensure proper placement. Confirmation should be made with the presence of end-tidal CO2 (EtCO2). If possible, positive pressure ventilation should be performed with lower tidal volumes, lower peak ventilation pressures, and higher respiratory rates. This will decrease leakage of air through damaged alveoli if pneumothorax is present. However, if the animal has a diaphragmatic hernia or pleural effusion, tidal volumes may be kept low but peak airway pressures may need to be higher to adequately ventilate the patient. If external pressures asserted on the lung tissue are completely compressing alveoli, bronchioles, and bronchi, it may take higher pressures to ventilate until the thorax is opened. When possible, however, smaller tidal volumes, higher respiratory rates, and lower peak airway pressures should be used. Dogs and cats with respiratory insufficiency should be maintained with inhalation anesthetics (i.e., isoflurane or sevoflurane) (Table 30-1). Inhalation anesthesia is advantageous because it allows rapid recovery and more precise control of anesthetic depth than does maintaining anesthesia with longer-acting intravenous anesthetics. Nitrous oxide should not be used in patients with pneumothorax or diaphragmatic hernias because it rapidly diffuses into air-filled spaces (i.e., pleural cavity or gas-filled organs) causing further lung compression or organ enlargement. Also, nitrous oxide is comparatively less soluble in plasma than are oxygen and other inhalation anesthetics; therefore, it rapidly diffuses into the alveoli when it is discontinued, resulting in diffusion hypoxia if the nitrous oxide is not turned off 5 to 10 minutes prior to extubation. Once surgery is completed, extubation should not be rushed. Make sure the patient is awake and not overly sedated, respirations are adequate, and the patient is comfortable prior to extubation. For specific anesthetic recommendations for animals with flail chest or pectus excavatum, see pages 974 and 985, respectively. Thoracoscopy is best done without insufflation; simply establishing a pneumothorax is sufficient for almost all cases. Should intrathoracic insufflation be required for thoracoscopy, it may have profound effects on cardiopulmonary parameters. If insufflation pressures exceed central venous pressures, venous blood flow return to the heart decreases, causing a significant drop in cardiac output and systemic blood pressure. If the heart rate also decreases, this can be an ominous sign of cardiovascular collapse. Therefore, insufflation-assisted thoracoscopy should be done with care using the lowest inspiratory pressure (IP) possible. Use of 5 cm H2O of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) increases the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaCO2) by decreasing shunt fraction and dead space in dogs with one lung ventilation, but it does not affect cardiac output (Kudnig et al, 2006). Therefore, PEEP is recommended with one lung ventilation. Thoracotomy procedures often cause substantial pain, and multimodal postoperative analgesic therapy is indicated (see also Chapters 12 and 31). Performing intercostal nerve blocks prior to extubation can provide significant analgesia in the immediate postoperative period (see Box 31-2 on p. 992). Injectable analgesics may also be used (i.e., hydromorphone, butorphanol, or buprenorphine; see Table 12-3 on p. 141). Although opioids are respiratory depressants, the analgesic effects of these drugs often outweigh the negative respiratory effects. If hypoventilation occurs after administration of opioids, oxygen should be given by nasal insufflation (see Chapter 4). Epidural administration of morphine is an effective analgesic in patients undergoing thoracic procedures and should be considered in any patient undergoing a thoracotomy (see Table 12-4 on p. 142). There is a delay of the onset of thoracic analgesia of approximately 6 to 8 hours. This coincides with the wearing off of the intercostal nerve blocks. When used together, nerve blocks and epidural morphine can provide substantial pain relief for the first 12 to 24 hours postoperatively. Epidural administration of morphine alone does not usually cause significant changes in cardiorespiratory measurements, but these patients should be monitored carefully for 24 hours for a delayed respiratory depression, especially when intravenous (IV) opioids are also administered. Obstruction of blood flow in the pulmonary vasculature by a thrombus or an embolus formed in the systemic venous system or right side of the heart is pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE). It may occur as a complication of a number of diseases (e.g., neoplasia, cardiac disease, sepsis, immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, hyperadrenocorticism, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and protein-losing nephropathy or enteropathy). It is difficult to diagnose antemortem because of the lack of specific signs. If it happens while the animal is under anesthesia, a rapid drop in EtCO2 may occur. This is followed by a significant drop in blood pressure, a rise in heart rate, and a decline in SpO2. Clinical signs associated with feline PTE include lethargy, anorexia, weight loss, and difficulty breathing. In dogs, vomiting, melena, fever, labored breathing, and lethargy have been reported. Risk factors for PTE include administration of corticosteroids, chemotherapeutic agents, or blood; indwelling catheters; and recent surgery. PTE should be suspected in animals with thoracic radiographic changes suggestive of uneven distribution of blood flow between lung lobes or patchy interstitial densities; pulmonary perfusion scintigraphy or computed tomography (CT) angiography may help confirm the diagnosis. Treatment of PTE includes anticoagulant and thrombolytic therapies plus standard hemodynamic and respiratory support (Box 30-1). Heparin acts primarily to limit the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin by accelerating the action of antithrombin III in inhibiting activated coagulation factors (II, IX, X, XI, and XII). Unfractionated heparin (UFH) has been most commonly used because of its widespread availability and low cost. It should be dosed to prolong the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) 1.5 to 2 times that of baseline. Fractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH; enoxaparin, dalteparin) differs from UFH in that it more specifically acts on factor X and is likely more effective. It also requires different monitoring than UFH and is more expensive. Prolongation of the aPTT does not occur at therapeutic doses of LMWH, but patients may be monitored by following clinical signs and assessing for anti-Xa activity. Warfarin prevents the formation of vitamin K–dependent coagulation factors (II, VII, IX, and X). It also inhibits production of protein C. Warfarin therapy is monitored using prothrombin time (PT) and the calculated international normalization ratio (INR). The traditional end point of warfarin therapy is a PT of 1.5 to 2 times that of baseline; however, due to variations in the PT assay, PT standardization is best achieved using INR (Box 30-2). The therapeutic range of warfarin is an INR of 2.0 to 3.0. Low-dose aspirin administration to inhibit platelet activity may be considered, but care must be taken to ensure that the aspirin does not cause renal or gastrointestinal complications, especially in patients receiving steroids or other nephrotoxic drugs. Appropriate use of prophylactic antibiotics depends on the length of surgery, the type of surgery being performed, the animal’s immune status, and the underlying disease process. Debilitated animals undergoing thoracotomy for removal of large neoplastic lesions (which may contain focal areas of necrosis) are likely to benefit from prophylactic antibiotic therapy. Prophylactic antibiotics should be given intravenously at induction of anesthesia and generally discontinued within 12 to 24 hours (see Chapter 9). The thoracic cavities of dogs and cats are compressed laterally; therefore, the greatest dimension is dorsoventral. The ribs, sternum, and vertebral column form the thoracic skeleton. The sternum is composed of eight unpaired bones and forms the floor of the thorax (Fig. 30-1). The first and last sternebrae are known as the manubrium and xiphoid, respectively. There are usually 13 pairs of ribs. The tenth, eleventh, and twelfth ribs do not articulate with the sternum but instead form the costal arch bilaterally. The cartilaginous portion of the thirteenth rib terminates free in the musculature. The space between the ribs, known as the intercostal space, generally is two to three times as wide as the adjacent ribs. Blood supply to the thoracic wall is provided by the intercostal arteries, which lie caudal to the adjacent rib in conjunction with a satellite vein and nerve. A typical intercostal nerve begins where the dorsal branch of the thoracic nerve divides and runs distally among the fibers of the internal intercostal muscle. In most intercostal spaces, intercostal vessels and nerves are covered medially only by the pleura. The lungs of dogs and cats have deep fissures that create distinct lobes, which allow the lungs to alter their shape in response to alterations in the shape of the thoracic cavity (i.e., that caused by diaphragmatic movement or flexion or extension of the spine). These fissures also allow individual lobes to be isolated and removed without compromising the integrity of the surrounding lobes. The left lung is divided into a cranial lobe, with a cranial and caudal part, and a caudal lobe (Fig. 30-2). The right lung is larger than the left and is divided into cranial, middle, caudal, and accessory lobes (see Fig. 30-2). The cardiac notch is a small area overlying the heart where lung tissue is not interposed between the heart and body wall. It usually is located at the ventral aspect of the fourth intercostal space and is larger on the right side. Thoracotomy may be performed by incising between the ribs or by splitting the sternum. The approach used depends on the exposure needed and underlying disease process. Regardless of the type of thoracotomy performed, a large area should be prepared for aseptic surgery to allow extension of the incision if needed. Depending on which left lobe is affected, a left lateral thoracotomy at the fourth, fifth, or sixth intercostal space provides adequate exposure for lobectomy (Table 30-2). A left fourth intercostal space thoracotomy allows exposure of the right ventricular outflow tract, main pulmonary artery, and ductus arteriosus. Bilateral removal of the pericardial sac can be difficult from this approach. A right intercostal thoracotomy provides exposure of the right side of the heart (auricle, atrium, and ventricle), cranial and caudal vena cava, right lung lobes, and azygous vein. Median sternotomy affords exposure to both sides of the thoracic cavity. Bilateral, partial lobectomy is easily performed from a median sternotomy; however, complete lobectomy often is difficult. The caudal vena cava, main pulmonary artery, and both sides of the pericardial sac can be isolated and manipulated through this approach. Recommended Intercostal Spaces for Thoracotomy* PDA, Patent ductus arteriosus; PRAA, persistent right aortic arch. *Numbers in parentheses indicate alternative surgical sites. Modified from Orton EC: Thoracic wall. In Slatter D, editor: Textbook of small animal surgery, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1993, WB Saunders. With the dog in lateral recumbency, select the site for incision. Locate the approximate intercostal space, and sharply incise the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and cutaneous trunci muscle. The incision should extend from just below the vertebral bodies to near the sternum. Deepen the incision through the latissimus dorsi muscle with scissors (Fig. 30-3, A), then palpate the first rib by placing a hand cranially under the latissimus dorsi muscle. Count back from the first rib to verify the correct intercostal space. The ribs cranial to an intercostal incision are more easily retracted than the caudal ribs; therefore, choose the more caudal space if you must choose between two adjacent intercostal spaces. Transect the scalenus and pectoral muscles with scissors perpendicular to their fibers, then separate the muscle fibers of the serratus ventralis muscle at the selected intercostal space (Fig. 30-3, B). Near the costochondral junction, place one scissor blade under the external intercostal muscle fibers, and push the scissors dorsally in the center of the intercostal space to incise the muscle (Fig. 30-3, C). Incise the internal intercostal muscle similarly. Notify the anesthetist that you are about to enter the thoracic cavity and, after identifying the lungs and pleura, use closed scissors or a blunt object to penetrate the pleura. This allows air to enter the thorax, causing the lungs to collapse away from the body wall. Extend the incision dorsally and ventrally to achieve the desired exposure. Identify and avoid incising the internal thoracic vessels, as they course subpleurally near the sternum. Moisten laparotomy sponges and place them on the exposed edges of the chest incision. Use a Finochietto retractor to spread the ribs (Figs. 30-3, D, and 30-4). If further exposure is necessary, a rib adjacent to the incision can be removed; however, this is seldom required. Close the thoracotomy by preplacing four to eight sutures of heavy monofilament absorbable or nonabsorbable suture (3-0 to No. 2, depending on the animal’s size) around the ribs adjacent to the incision (Fig. 30-5, A). Approximate the ribs with a rib approximator or have an assistant cross two sutures to appose the ribs (Fig. 30-5, B), then tie the remaining sutures. Tie all the sutures before you remove the rib approximator. Suture the serratus ventralis, scalenus, and pectoralis muscles in a continuous pattern with absorbable suture material. Appose the edges of the latissimus dorsi muscle similarly. Remove residual air from the thoracic cavity using the preplaced chest tube or an over-the-needle catheter (see p. 997). Close the subcutaneous tissue and skin in a routine fashion. In large dogs, sternotomies closed with wire are more stable, and healing is associated with chondral or osteochondral bridging. Single or double-twist figure-8 patterns centered between two sternebrae are associated with least displacement during biomechanical loading (Davis et al, 2006). With the dog in dorsal recumbency, incise the skin on the midline over the sternum. Expose the sternum by a combination of sharp incision and blunt dissection of the overlying musculature. Transect the sternebrae longitudinally on the midline with a sternal saw (Fig. 30-6), bone saw (Fig. 30-7), or chisel and osteotome. A sternal saw has a guide that sits under the sternum, making it much easier to cut the sternum without damaging the heart or lungs underneath. In young animals, heavy straight scissors may be adequate; however, avoid crushing the bone. Splitting the sternebrae on the midline facilitates closure. If using a bone saw or chisel, take extra precaution to ensure that the underlying lung and heart are not damaged while completing the sternotomy. Place moistened laparotomy sponges on the incised edges of the sternebrae and retract the edges with a Finochietto rib retractor. If a chest tube is to be placed, do so before closing the sternotomy. Do not exit the tube from between the sternebrae; exit it from between the ribs or through the diaphragm. Close the sternotomy with wires (dogs larger than approximately 15 kg) or heavy suture (cats and dogs smaller than approximately 15 kg) placed around the sternebrae in a figure-8 pattern (Fig. 30-8). Suture the subcutaneous tissue in a simple continuous pattern with absorbable suture. Remove residual air from the thoracic cavity and close the skin routinely. Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) or thoracoscopy is a minimally invasive technique for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures of the thoracic cavity. Thoracoscopy is performed in either dorsal recumbency with the camera portal placed in a paraxiphoid position or lateral recumbency with camera and instrument portals placed through intercostals spaces. To improve visualization and operative working space, one-lung ventilation or mainstem bronchial blockade can be performed. Procedures that can be performed by thoracoscopy include, but are not limited to, exploratory thoracotomy (e.g., pyothorax); biopsies of lung, mediastinum, or pleura; pericardiectomy; lung lobectomy; correction of vascular ring anomalies; thymoma removal; and thoracic duct ligation. Thoracoscopy is associated with less postoperative pain, fewer wound complications, decreased recovery time, shorter hospitalization periods, and more rapid return to function. See also Chapter 13. Identify the appropriate intercostal space, and make a 3- to 7-cm keyhole intercostal thoracotomy approach (see the previous discussion) to expose the lung. Place a small Finochietto rib retractor into the space to gain exposure to the thoracic cavity. Exteriorize the lung lobe and obtain a lung biopsy using an encircling ligature or thoracoabdominal (TA) stapler (see p. 969). Inspect the stump that remains after biopsy for evidence of hemorrhage and evaluate it for air leakage by filling the thoracic cavity with warm sterile saline solution and examining for air bubbles. Evacuate the fluid using suction. Place a chest tube if necessary, or close the chest routinely (see previous discussion) and aspirate air from the thoracic cavity with a needle or catheter (see p. 997). Identify the lung tissue to be removed, and place a pair of crushing forceps across the lobe proximal to the lesion (Fig. 30-9, A). Place a continuous, overlapping pattern of absorbable suture (2-0 to 4-0) 4 to 6 mm proximal to the forceps (Fig. 30-9, B). If necessary, place a second row of sutures in a similar manner. Excise the lung between the suture lines and clamps, leaving a 2- to 3-mm margin of tissue distal to the sutures (Fig. 30-9, C). Oversew the lung in a simple continuous pattern with absorbable suture (3-0 to 5-0; Fig. 30-9, D). Replace the lung in the thoracic cavity and fill the chest cavity with warmed sterile saline solution. Inflate the lungs and check the bronchus for air leaks. Remove the fluid before closing the thorax.

Surgery of the Lower Respiratory System

Lungs and Thoracic Wall

Preoperative management

Anesthesia

Antibiotics

Surgical Anatomy

Surgical Technique

![]() TABLE 30-2

TABLE 30-2

Left

Right

Heart

4,5

4,5

PDA

4(5)

PRAA

4

Pulmonic valve

4

Lungs

4-6

4-6

Cranial lobe

4,5

4,5

Middle lobe

5

Caudal lobe

5(6)

5(6)

Esophagus

Cranial

3,4

Caudal

7-9

7-9

Cranial vena cava

(4)

4

Caudal vena cava

(6-7)

6-7

Intercostal thoracotomy

Median sternotomy

Thoracoscopy

Lung Biopsy

Keyhole biopsy

Partial Lobectomy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Surgery of the Lower Respiratory System: Lungs and Thoracic Wall