Chapter 5 Surgery of the eyelids

Preoperative examination procedures 93

Surgical considerations of the eyelids 94

Surgical preparations of the eyelids 95

Tarsorrhaphy in small animals 95

Aftercare for eyelid surgery in the horse 97

Surgical procedures for eyelid agenesis 98

Surgical procedures for distichiasis 100

Surgical procedures for ectopic cilia 103

SURGICAL PROCEDURES FOR ENTROPION IN SMALL ANIMALS 103

Non-surgical treatment of entropion 103

Surgical management of entropion 105

Postoperative management and complications 111

ADAPTATIONS IN LARGE ANIMALS AND SPECIAL SPECIES 112

Entropion and periocular fat pads in the Vietnamese potbellied pig (Sus scrofa) 113

SURGICAL PROCEDURES FOR ECTROPION 114

Surgical procedures for combined ectropion and entropion 117

Surgical procedures to decrease palpebral fissure size 120

Surgical procedures to increase palpebral fissure size 122

Nasal fold trichiasis and resection in dogs 123

Surgical treatment of chalazion 123

Surgical repair of eyelid lacerations 123

Surgical procedures for minor eyelid neoplasms in small animals 126

Reconstructive blepharoplasty after removal of eyelid masses in small animals 128

Surgeries for eyelid neoplasia in the horse 132

Blepharoplastic procedures for the horse 133

Introduction

Anatomy

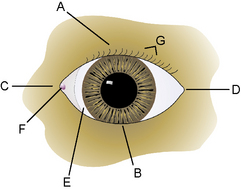

The morphology of the eyelids in domestic animals is quite similar, with size being the major variable. The eyelids represent the transition of the integument system and the beginning of the ophthalmic apparatus with the initiation of the palpebral conjunctiva. The eyelids surround the palpebral fissure, through which the eye contacts the environment. The eyelids are divided clinically into the dorsal, superior, or upper eyelid; the ventral, inferior, or lower eyelid; the medial or nasal canthus; and the lateral or temporal canthus (Fig. 5.1). The dorsal eyelid is the largest, most mobile, and 2–5 mm longer than the lower lid. Distinct ligaments, the septum orbitale, and certain muscles attach at both sides of the palpebral fissure, resulting in an oval rather than round eyelid opening. The medial canthal eyelid area is relatively fixed to the subcutaneous tissues and periosteum by the medial palpebral or canthal ligament. Protected immediately behind the medial canthal ligament is the nasolacrimal sac. The lateral canthal region is more mobile, especially in dogs. The lateral canthal ligament is poorly developed in the dog and is replaced by the retractor anguli oculi lateralis muscle. Hence in dogs, defects often affect the lower lid and lateral canthus.

Eyelid skin, cilia (eyelashes), and glands

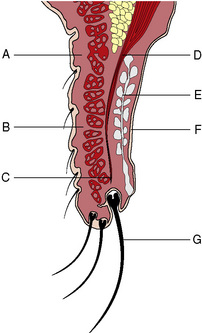

The skin of domestic animal eyelids is thinner than other parts of the integument system (Fig. 5.2). Eyelid movements require both thin and pliable skin. Fine short hairs normally cover the eyelid skin. The subcutaneous tissues under the eyelid skin are relatively thin and attach the lid skin to the deeper orbicularis oculi muscle. Cilia or eyelashes occur primarily on the canine upper eyelid, usually in two or four irregular rows. These cilia are usually the same color as the adjacent eyelid hair coat. Long tactile hairs (pili supraorbitales or vibrissae) appear as a tuft along the dorsal medial orbital margin in several animal species. Eyelashes are not present in cats, although the eyelid hair next to the dorsal eyelid margin may be considered a substitute. Two types of gland, the glands of Moll and glands of Zeis, are located about the cilia follicles. The gland of Moll is a modified sweat (apocrine) gland and the gland of Zeis is a modified sebaceous gland. These glands can become inflamed and abscessed in young animals, resulting in the formation of a stye or external hordeolum. The margo-intermarginalis represents the free margin of the eyelids.

Eyelid muscles

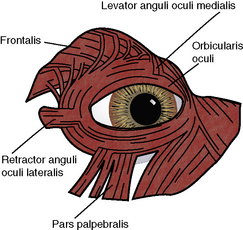

Several muscles are involved in opening the eyelids and increasing the size of the palpebral fissure in the dog and cat. In the canine upper eyelid these muscles consist of (medial to lateral) the levator anguli oculi medialis, levator palpebrae superioris, and the frontalis, and in the lower lid, the pars palpebralis of the sphincter colli profundus (Fig. 5.3). The levator palpebrae superioris muscle has its origin deep within the orbit, along with the rest of the extraocular muscles, and lies immediately above the dorsal rectus muscle that inserts several millimeters from the dorsal limbus of the globe. Fascial attachments between the dorsal rectus and levator palpebrae superioris muscles result in simultaneous upper movements of the globe and retraction of the upper eyelid. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle seems to be the most important muscle for upper lid retraction as damage to this muscle or its insertions into the tarsal layer results in ptosis (or drooping of the upper eyelid). The levator anguli oculi medialis muscle elevates the medial upper eyelid and erects the long tactile hairs of the eyebrow. In some of the large breeds of dogs, the action of this muscle results in a noticeable notch at the junction of the medial and middle one-thirds of the upper lid. In the dog, Müller’s smooth muscle fibers, innervated by the sympathetic nerves, attach to the upper tarsus; in the cat, these muscle fibers also attach to the nictitating membrane. With the release of endogenous adrenaline (epinephrine), or during the fight-and-flight reflex, these adrenergic innervated smooth muscle fibers can immediately increase the size of the palpebral fissure.

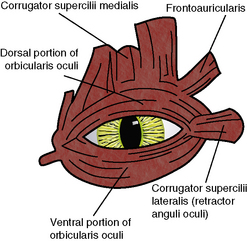

The lateral palpebral or canthal ligament is poorly developed in dogs and cats, and usually consists of an irregular thickened lateral septum orbitale. In the large breeds of dogs the lack of or a poorly developed lateral canthal ligament contributes directly to lateral canthal lid diseases in these breeds. The major component of the lateral canthal support system has been replaced by the retractor anguli oculi lateralis (dog) or corrugator supercilii lateralis (cat) muscle (Fig. 5.4). This results in a somewhat mobile but unstable lateral canthus in dogs, and contributes to the frequent involvement of the lateral canthus and lateral lower and upper eyelids with entropion and ectropion. The lateral one-half of the lower eyelid in the dog also has the pars palpebralis muscle, a subdivision of the sphincter colli profundus muscle, which can depress the lateral lower lid.

Preoperative examination procedures

In the dog, a few milliliters of local anesthetic are injected subcutaneously along the dorsal aspects of the middle portion of the zygomatic arch to block the palpebral branch of the facial nerve and the primary innervation to the orbicularis oculi muscle that closes the palpebral fissure (Fig. 5.5). Within a few minutes, total loss of eyelid muscle tone will occur, and the extent of the eyelid problem to be corrected surgically can be determined.

In the horse, the auriculopalpebral nerve can be blocked at at least two sites (see Fig. 3.5, p. 44). The auriculopalpebral nerve can be blocked by infiltrating local anesthetic in a fan-like manner subfascially in the depression just caudal to the posterior ramus of the mandible at the ventral edge of the temporal portion of the zygomatic arch. The hypodermic needle is directed dorsally just caudal to the highest point of the arch. Before injecting local anesthetic, aspiration is performed to prevent injection into the rostral auricular artery or vein. This procedure may also result in akinesia of the ear muscles as well as gravitate ventrally and affect other branches of the facial nerve. Within a few minutes, total loss of eyelid muscle tone will occur, but lid sensation is still present.

Surgical instrumentation

The instrumentation for eyelid surgery usually consists of a mixture of general soft tissue instruments, as well as selected ophthalmic instruments. The recommended ophthalmic instruments include small straight and curved strabismus or tenotomy scissors to cut tissues and sutures, both teeth (1 × 2) and serrated thumb forceps (such as Bishop–Harmon forceps), small scalpel blades (Nos 6400 and 6500 microsurgical), small wire eyelid speculum, and a standard ophthalmic needle holder (often with lock). Special thumb forceps, such as chalazion and entropion forceps, are useful to clamp and stabilize the eyelids during surgery (see Table 1.3, p. 12).

Tarsorrhaphy in small animals

Permanent tarsorrhaphy

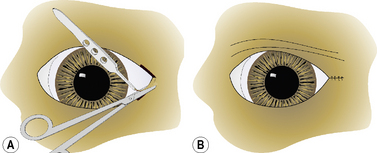

In the permanent tarsorrhaphy procedure the upper and lower eyelid margins are trimmed by curved Metzenbaum scissors 3–5 mm from the lid margins (Fig. 5.6a). This area is usually where the eyelid pigmentation stops and the eyelid hair appears. For complete permanent tarsorrhaphy the entire eyelid margins are excised for 360°, with special care to adequately excise the lid margins at the two canthi. For partial permanent tarsorrhaphy any section of the eyelid may be used, but most often the lateral and medial canthal areas are involved. At a depth of 4–5 mm, the bases of the meibomian glands are excised. The eyelids are usually apposed by two layers of sutures in most dogs (Fig. 5.6b); however, in miniature breeds, a single suture layer may suffice. The deeper tarsopalpebral layer is apposed with either 4-0 to 6-0 simple interrupted or a simple continuous absorbable suture placed submucosally to avoid corneal contact. The eyelid skin–orbicularis oculi layer is usually apposed with 4-0 to 6-0 simple interrupted or interrupted mattress non-absorbable sutures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree