Chapter 9 Surgery of the Bovine Respiratory and Cardiovascular Systems

Need for surgical treatment for respiratory and cardiovascular disease in cattle is not common. However, several disorders are well documented and are most expediently addressed with surgical therapy. Although some of these disorders are congenital malformations, the majority are infectious in origin. Thorough physical examination can often determine an accurate diagnosis and the treatment most likely to be successful. Several ancillary diagnostic exercises can assist physical examination findings to further direct specific treatment selection. This chapter will focus on surgical considerations in the treatment of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, but other factors such as cost, genetic potential, and other business considerations should be included in the decision-making process.

Diagnostics

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

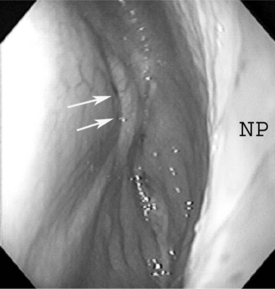

The upper respiratory tract can be evaluated relatively readily via palpation, percussion, and auscultation. The nares of cattle should be moist and readily and regularly cleaned by the tongue; therefore the presence of even serous nasal discharge is abnormal. The openings of the nares do not flare or move as much as those of horses. Patency of the nares and nasopharynx can be readily accomplished by placing cupped hands in front of the nares and assessing the volume of air flow or, in cold climates, observing the condensed expired air. Inspiration is difficult to assess, but the relative volume of expired air can be readily determined. Symmetry of air flow may be the most important aspect of expiration to be determined at the nares. The nature of any fluid at the nares should be examined. Expired air should be evaluated for odors that may be indicative of an infectious and/or necrotic process. Any abnormal sounds associated with inspiration or expiration should also be noted. Audible whistles, gurgles, or other abnormal sounds can be indicative of upper airway compromise.

The ventral aspect of the head should be visually examined and palpated. The intermandibular space should be examined for swelling and painful response to palpation. Congenital malformation, trauma associated with bawling gun injury or foreign body penetration may result in a perilaryngeal mass that can compromise the upper respiratory tract at the pharynx, larynx and proximal trachea. These can be suspected by detection of proximal cervical swelling (see Figure 10-14). The cervical locations of palpable lymphatic tissues should be closely examined visually and by hand. The trachea should be auscultated with attention to airflow, or abnormal sounds indicating the presence of fluid. The trachea and tracheal region should be palpated. Subcutaneous crepitation should be noted. Tracheal sensitivity to pressure and the ease of eliciting a cough should also be determined.

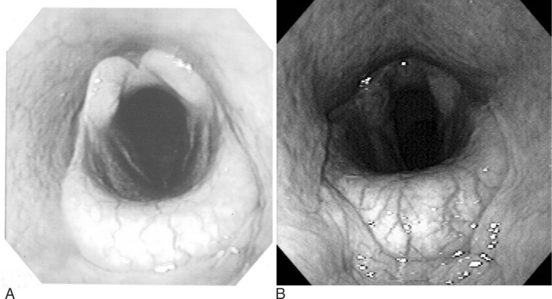

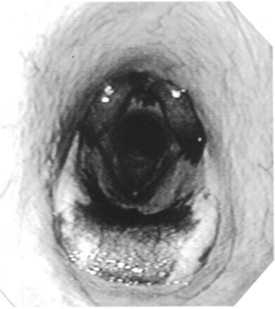

ENDOSCOPIC EXAMINATION

IMAGING EXAMINATION

Ultrasonography can be a very helpful tool in evaluating the airway for disease. It should be recalled that sound waves reflect from gas or air; therefore the aerated aspects of the respiratory tract cannot be satisfactorily imaged. However, a great deal of indirect information can be obtained with ultrasonography. Soft tissue facial distortion, peritracheal swelling, and pleural space fluid accumulation can be readily assessed. Ultrasonography is indicated anytime soft tissue or fluid-associated abnormalities are evaluated in and around the respiratory tract of cattle.

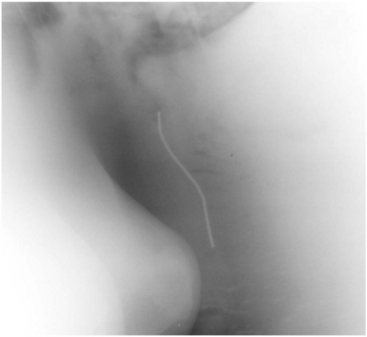

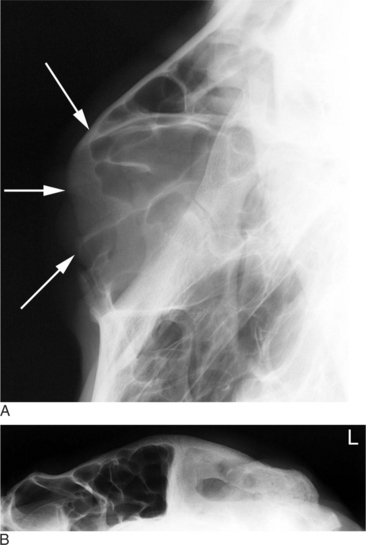

Radiography can also be critical in imaging the respiratory tract of cattle. The upper airway is best imaged with lateral and dorsoventral radiographic projections. However, various oblique views can certainly assist in defining mass lesions and lesions associated with fluid accumulation. With the increasing availability of three dimensional imaging, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can assist the clinician in completing diagnoses in cattle. However, animal size and economic considerations will likely limit the practicality of these imaging modalities. The lower airway can also be imaged with radiographs (Figure 9-6); however, animal size often interferes with the ability to identify abnormalities. It should be assumed that radiographic detail will be lost as body size increases. When one is considering the caudal thorax and cranial abdomen, positioning the bovine patient may be an important for successful radiographic assessment. Metallic foreign material that penetrates the reticulum and entering the thoracic cavity may be more easily identified radiographically with the patient in dorsal recumbency rather than standing (Figures 9-7 and 9-8). This allows for reduced tissue thickness and better detail of reticular and pericardial structures with the gas content displaced in the ventral aspect of the reticulum. Care should be exercised as some animals do not tolerate casting or the sedation needed for this position. Dorsal recumbency is not advised for very sick and/or debilitated animals or animals with impaired ventilation.

Figure 9-6 Pleural fluid accumulation in a cow with septic pleuritis.

(Courtesy of Dr. A. Yeager, Cornell University.)

Upper Airway

NASAL OBSTRUCTION

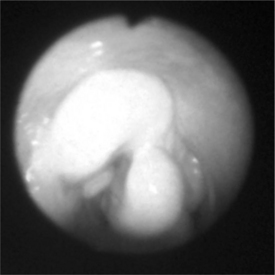

Nasal obstruction in cattle, as in other animals, is typically marked by respiratory noise, which is readily localized to the upper airway. Unilateral obstruction can usually be detected with cupped hands near the nares to evaluate symmetry of expiration. Bilateral obstruction is accompanied by severe dyspnea and often with labored open-mouthed breathing. Disease entities most commonly associated with nasal obstruction include congenital malformation—such as conchal cyst (Figure 9-9) and choanal atresia—and acquired conditions, such as granulomas, polyps, and neoplasia (i.e., adenocarcinoma).

Physical and endoscopic examinations in combination with radiography can usually delineate the presence of a discrete mass lesion (see Figure 9-9). This is desirable when surgical treatment is considered, as a specific target helps in formulating a surgical plan. Some small and pedunculated nasal masses can be resected with transendoscopically-guided long instruments, wire loop (with or without cautery), or laser. Small masses may also be amenable to traditional trephination approaches and therefore can be removed in standing cattle. It is pos-sible to resect membranous choanal atresia using a laser (Nd : Yag or diode) under video endoscopic guidance, but a well vascularized membrane can hemorrhage and obstruct vision of the surgery site.

The typical preanesthetic preparations (including acceptable antibiotic and antiinflammatory therapies), induction and maintenance of general anesthesia are recommended (see Chapter 6). Orotracheal intubation is essential to allow surgical manipulation within the nasal cavity. Lateral recumbency with the affected nasal side uppermost is usually a satisfactory position for unilateral disease. On rare occasions, sternal recumbency is desirable to reach bilateral lesions from a single incisional approach. A flap should be designed to allow as complete exposure as possible without potentially damaging vital structures. It should be noted that many—if not most—facial flaps will enter the paranasal sinuses. This is especially true in the caudal region of the nasal passages. The maxillary and frontal sinuses are often the first cavity entered in an approach to the nasal cavity.

A curvilinear skin incision is made over the underlying bone and soft tissues that require elevation. Periosteum should be sharply incised, gently elevated, and moved from the line of incision into bone. An oscillating bone saw is ideal for this procedure; however, an osteotome and mallet can also be successful in producing a bone flap. The rostral, caudal, and axial aspects of the bone flap should be completely osteotomized. The dorsal and rostral aspects should be “notched” at the corners to allow the flap to be gently hinged away from the normal position. This generally produces good exposure to allow needed manipulations of diseased tissues in the nasal cavity. The nasal passages and paranasal sinuses are highly vascular regions, and extensive hemorrhage should be expected with aggressive manipulations. Hemostasis is difficult to obtain without direct packing of gauze into the affected airways. With unilateral surgical procedures, firm packing of the affected airway with continuous rolled gauze is very effective in controlling bleeding. In our experience, nasal bleeding is not as marked in cattle in comparison to horses. If bilateral disease is present, a tracheostomy should be placed. The gauze packing can be exited from the nares and secured to the skin. Alternatively, the packing can be exited from the lateral aspect of the incision. This usually requires removal of a corner of bone with a rongeur forceps or osteotome. The bone flap can be repositioned and manually pushed back to its normal position. Periosteum, subcutaneous tissues, and skin are then closed. The facial bone of the flap can be wired to the parent bone, but this is rarely necessary if the overlying soft tissues can be successfully closed.

DISORDERS OF THE PARANASAL SINUSES

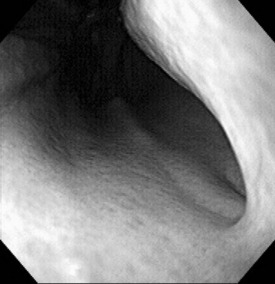

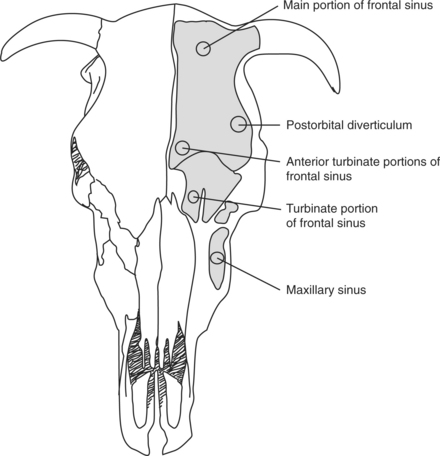

Diagnosis of paranasal sinus disease is based upon physical examination findings and imaging studies. On physical examination, bulging of the sinus and purulent exudates at the site of dehorning or nasal discharge are typical of sinusitis (Figure 9-10). Endoscopy may help rule out other sources of nasal discharge, but the best definition of sinus involvement is obtained with radiography. Lateral and dorsoventral radiographic projections will delineate abnormal soft tissue and fluid components within the airspace and walls of the sinuses (Figure 9-11, A and B). Occasionally, oblique projections may be necessary to more fully understand the extent of the disease process. Final etiologic diagnosis depends on microbial culture, cytology, and/or histology of the abnormal tissues within the affected sinus. This may be obtained from sinus centesis and aspiration after a small trephine hole is produced with a Steinmann pin (4 mm or 5/32 inch). Actinomyces pyogenes is commonly isolated after dehorning, and Pasteurella multocida is often associated with sinusitis unrelated to dehorning.

Refractory or chronic infectious sinusitis is best treated by open drainage and lavage of the affected sinus. This is most directly performed with 1 or 2 trephine holes positioned to allow drainage. The site of trephination for each sinus is indicated in Figure 9-12. This can be done with physical restraint and local anesthesia. Generally, the site of drainage is localized in the middle of the bulging frontal or maxillary bone. The frontal sinus is the most commonly affected sinus, and one needs to effectively drain the postorbital diverticulum. The drainage site is 4 cm caudal to the caudal edge of the orbit just above the temporal fossa (Figure 9-12A). The rostral site of the frontal sinus can be drained by trephining 2.5 cm from the midline on a line passing through the orbit center (Figure 9-12B). The turbinate part of the frontal sinus can be drained by trephining just caudal to the nasal bone divergence point, again 2.5 cm from midline (Figure 9-12C). The main part of the frontal sinus can also be trephined if it bulges (Figure 9-12D). A ¾-inch (19 mm) trephine is recommended. Additional trephine holes may be required, depending on individual needs. The maxillary sinus can be opened with a trephine hole immediately dorsal and caudal to the facial tubercle. It may be necessary to place this hole more dorsally in younger cattle to avoid the maxillary teeth. After trephination, large volume lavage with sterile fluid is often necessary to remove exudate and debris. Saline (0.9%), lactated Ringer’s, or tap water with povidone iodine solution can work well. Occasionally, debridement will be required to completely remove inspissated material and necrotic tissue. This can be performed though the trephine holes or a more aggressive sinus flap. The technique is the same as described for the various approaches to the nasal passages. Flaps should be elevated toward midline with sufficient exposure to accomplish the necessary excision or debridement. General anesthesia is usually required when large flaps are considered. Complete curettage and aggressive lavage are easier to perform via a sinus flap. Voluminous hemorrhage is more likely after creation of a flap and aggressive intrasinus manipulation. Therefore packing the sinus with gauze may be required before flap closure. Creating portals for lavage and drainage is recommended before closing the flap. Removing one or two corners of the facial bone flap allows easy access for subsequent lavage. This is essential to resolve septic disease pro-cesses in conjunction with systemic and local antibiotic therapy.

Cattle with infectious sinusitis appear to respond well to surgical treatment if it is performed prior to general debilitation and development of deteriorating secondary clinical signs. If a neoplastic disorder causes the sinusitis, treatment (surgical debridement of an affected sinus) is palliative, but long-term prognosis is poor because complete excision is usually not possible.

DISORDERS OF THE NASOPHARYNX

Localized infectious disease is the most common disorder of the bovine pharynx. Trauma from puncture or laceration can be problematic and can also result in abscess, hematoma, or granuloma formation in the pharyngeal and retropharyngeal tissues (see Figure 10.1-4). Lymph node abscesses can also result from delivery of bacteria to lymphatic tissue in this region. Pharyngeal polyps and various neoplastic disorders have been reported in cattle but are rare. Finally, cleft palate is occasionally seen in cattle (see Figure 10.1-20). Most cleft palates are congenital, but injury during oral administration of medi-cation can occasionally result in iatrogenic palate laceration. Animals with cleft palate typically present with nasal regurgitation of milk, water, and food material immediately after eating. They are likely to have secondary aspiration pneumonia, and signs of lower airway disease may be present.

Pharyngeal trauma that does not result in abscess formation rarely requires surgical treatment. Instead, systemic antibiotics, analgesics, and medical therapy (appropriate fluid and electrolyte supplementation) can often lead to resolution of lacerations, hematomas, and granulomas. However, if cervical cellulitis (see Section 10.1) and/or a pharyngeal abscess develops, surgical drainage is the most expedient means of returning to normal function (see Section 10.1 for management of cervical cellulitis secondary to oropharyngeal disease). An abscess can cause significant upper airway obstruction and requires immediate attention to prevent suffocation. Depending on the degree of airway compromise, a temporary tracheostomy may be needed before surgical intervention. Abscesses in—or very near—the pharyngeal wall can often be incised and drained into the pharyngeal cavity. Retropharyngeal and perilaryngeal abscesses are more common than abscesses directly in the pharyngeal wall. These abscesses usually result from trauma or esophageal rupture or develop in regional lymph nodes. As for pharyngeal abscesses, the diagnosis is usually based on clinical signs that can vary from local swelling to dyspnea, anorexia, excessive salivation, and dysphagia. Ultrasonography and radiography can help more accurately define the location, structure, and quantity of abscesses (see Figure 10.1-6, A). These imaging techniques can also confirm the presence of foreign material that requires removal. The treatment of retropharyngeal abscesses is also based on establishing good ventral drainage.

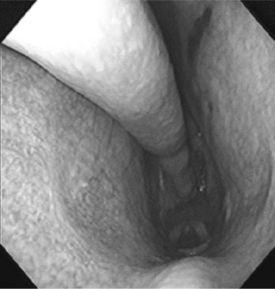

Persistent dorsal displacement of the soft palate is an extremely rare cause of upper airway obstruction in farm animals. Unlike horses, dorsal displacement of the soft palate results in respiratory noise that is most evident on inspiration, although it is apparent on expiration as well. Diagnosis is suspected on the basis of upper respiratory noise and confirmed by endoscopy. If the upper airway obstruction is significant, strap muscle resection has been shown effective in relieving DDSP. The procedure can be done with the animal standing, head tied-up, and the middle cervical infiltrated with local anesthetic. Alternatively, general anesthesia can be used. After aseptic preparation of the area, a 10-cm ventral midline incision in the cranial cervical region is used to expose the sternohyoideus and sternothyroideus muscles at the ventral and ventrolateral aspects of the trachea. These muscles are elevated and transected, and a segment (10 cm) of each muscle is resected. The subcutaneous tissues and skin are closed separately. Normal husbandry and function as well as reduction of respiratory noise have been reported within 24 hours of surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree