Chapter 6 Surgery of nasolacrimal apparatus and tear systems

Nasolacrimal apparatus

Nasolacrimal anatomy in dogs and cats

The nasolacrimal apparatus consists of the upper and lower lacrimal puncta, the upper and lower canaliculi, the lacrimal sac, and the long nasolacrimal duct that empties into the rostral nasal cavity (Fig. 6.1). Although there are considerable variations in head shape and size in the different breeds of dogs, the predominant anatomic variation of the nasolacrimal apparatus is the variable length and diameter of the nasolacrimal duct.

Clinical diagnostic tests for the nasolacrimal drainage apparatus

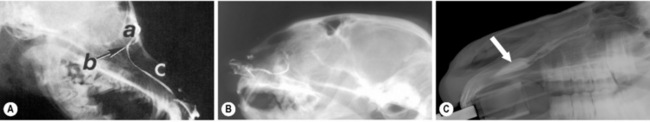

Visualization of the nasolacrimal system is possible in all animal species with dacryocystorhinography (Fig. 6.2). Observation of the system may be necessary when there is medically non-responsive or recurrent nasolacrimal sac or duct obstructions, or the possibility of nasal cavity masses. For dacryocystorhinography, general anesthesia of the patient and at least two radiographic views of the nasolacrimal system are necessary. A viscid cardiovascular radio-opaque solution (0.2–0.7 mL) is slowly injected into the upper lacrimal punctum in small animals and about 4–6 mL in foals and adult horses; 10–30 s later at least two radiographic views are taken. Dacryocystorhinography can detect irregularities in both the system’s diameter and course, and is generally most useful prior to consideration of surgeries of the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct.

Nasolacrimal catheterization

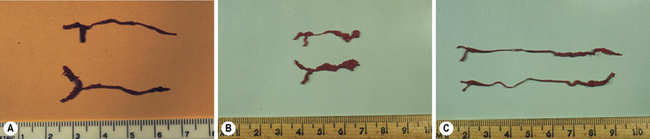

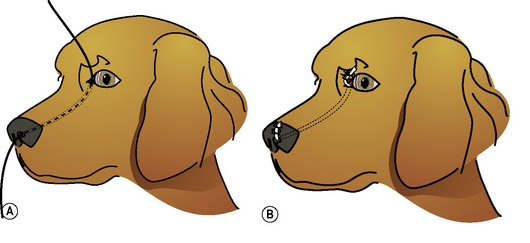

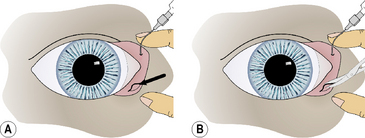

With the dog or cat under short-acting general anesthesia, a blunted (smooth melted end) 2-0 to 3-0 monofilament nylon suture is carefully inserted into the upper lacrimal punctum, upper canaliculus, lacrimal sac, and nasolacrimal duct to emerge from the external nares (Fig. 6.3a). The nylon suture can potentially become halted temporarily at the base of the lacrimal sac and at the accessory opening of the nasolacrimal duct immediately above the root of the upper canine tooth. Gentle turning and twisting of the suture can pass these barriers en route to the external nares. Once the nylon suture has traversed the system, PE 90 polyethylene, fine polyvinyl, or silicone tubing is slid over the entire length of the suture if a larger diameter cannula is preferred. The suture is removed leaving the tubing within the nasolacrimal system; both ends are attached by one or two simple interrupted non-absorbable sutures to the skin of the medial canthus and lateral of the external nares (Fig. 6.3b,c). In foals and adult horses, the entire nasolacrimal system from the upper or lower lacrimal punctum to its distal orifice can be easily traversed by a No. 5 French catheter.

Surgical procedures for the nasolacrimal apparatus

Surgery for imperforate lacrimal punctum

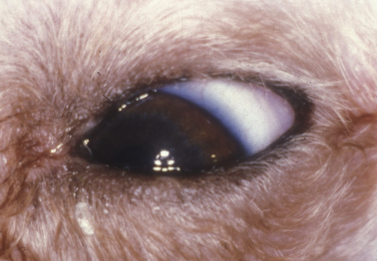

With the impaired drainage of tears with lower lacrimal punctum obstruction, excessive moisture and rust-colored staining of the medial canthal skin and hair are usually present (Fig. 6.4). Concurrent conjunctivitis is usually absent, but variable amounts of dermatitis of the eyelids and face may be present.

Close inspection of the medial lower palpebral conjunctiva detects the absence of the lower lacrimal punctum. The topical fluorescein test is usually delayed or negative. The nasolacrimal flush performed through the upper lacrimal punctum exits from the nasolacrimal duct and external nares, but not through the lower punctum. Observation of the medial lower palpebral conjunctiva during the initial injection of saline may reveal a slightly raised or ballooned area during the initial flush that corresponds to the orifice of the lower punctum (Fig. 6.5a).

The mucosa overlying the lower punctum may be excised, leaving an oval to round defect, or a cruciate incision may be performed in the area (Fig. 6.5b). The nasolacrimal flush is again performed to confirm patency. Topical antibiotic/corticosteroid solutions are instilled six to eight times daily for 10–14 days to maintain patency and prevent the orifice wall from healing together. Intracanalicular gelatin implants may also be used to maintain the punctum’s patency.

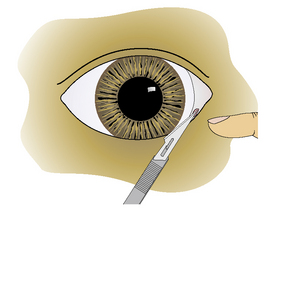

Enlargement of the lower punctum

Treatment consists of surgical enlargement of the lower punctum. Under short-acting general anesthesia, the opening of the micropunctum is incised with the Bard–Parker No. 11 scalpel or Beaver No. 6500 or 6700 microsurgical blade (Fig. 6.6). The knife blade is slid further into the lower canaliculus, and an additional 3–5 mm of canaliculus wall is incised. Alternatively, the mucosa around the lower punctum is incised into three sections and excised. Postoperative treatment consists of topical antibiotics and corticosteroids administered six to eight times daily to control the healing process and prevent fibrosis.

Dacryocystotomy

Surgical procedures of the canine and feline lacrimal sac are infrequent, as the sac is poorly developed, partially covered by the lacrimal bone, and caudal of the medial aspects of the orbicularis oculi muscle. Dacryocystitis is not infrequent in the dog. Foreign bodies, bacterial infections, and obstruction of the lacrimal sac characterize dacryocystitis. Occasionally a fistula may develop from the lacrimal sac onto the skin of the medial canthus (Fig. 6.7). Dacryocystitis usually responds to a combination of nasolacrimal flushes and antibiotic therapy. For recurrent dacryocystitis, nasolacrimal catheterization is recommended. In those patients that do not respond to these treatments, an exploratory dacryocystotomy for foreign bodies is recommended.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree