19 Specialized dietary supplements

Introduction

There are various definitions in the published literature for a “dietary supplement”. In a recent review for the National Research Council’s (NRC 2009) Safety of Dietary Supplements for Horses, Dogs and Cats. The Committee on Examining the Safety of Dietary Supplements for Horses, Dogs and Cats defined an animal dietary supplement as:

Another definition from The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines a dietary supplement as:

by the Foundation for Innovation in Medicine (1991). Under such a description nutraceuticals could include nutrients (e.g., vitamin E), derivatives of nutrients (e.g., glucosamine), or herbs. Herbal medicine, also called “phytomedicine”, is the use of therapeutic plants, plant parts or plant derived substances to aid in fighting against infections, diseases or enhancing overall health. However, in many countries, feed products with claims related to the prevention or treatment of disease are not legally allowed to be sold (exceptions include defined dietetic feeds).

Nutrients with established requirements (but fed in amounts far greater than minimal requirements, as defined by the NRC 2007)

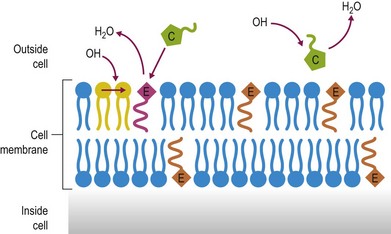

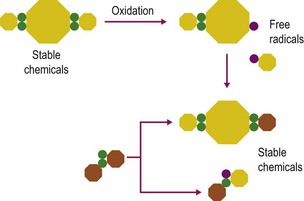

Antioxidants including many vitamins (e.g., vitamins E and C), minerals (e.g., selenium), enzymes (e.g., superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase) and nutrient derivatives (e.g. glutathione, lipoic acid) are often included as various mixes or cocktails within specialized supplements. The aim is to counter the negative effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or free radicals (see Figs 19.1 and 19.2 for an illustration of antioxidant action). Oxidative stress occurs when the antioxidant defense system in the body is overwhelmed with ROS (McBride & Kraemer 1999). ROS are primarily generated within the mitochondrial electron transport chain. An increase in ROS may occur due to a) increased exposure to oxidants from the environment, b) an imbalance in antioxidants, or c) increased production within the body from an increase in oxygen metabolism during exercise (Clarkson & Thompson 2000). Antioxidants are most effective when acting in combination with each other as some have the ability to recycle antioxidant radicals that are formed during the scavenging of ROS. For example, vitamin E forms a tocopherol radical that is inactive until glutathione or ascorbate reacts with the radical and returns it back to its active form. For detailed discussion on the mode of action of these antioxidants please refer to the relevant chapters in this book dealing with each nutrient.

Vitamin E

Potential rationale for use

Vitamin E has strong antioxidant properties that are postulated to help support muscle and nerve as well as immune function (see also Chapter 17). Vitamin E is the major lipid-soluble, chain–breaking antioxidant of the body and provides antioxidant defence in cells, playing an important role in maintaining the integrity of cell membranes (see Chapter 9).

Data on efficacy

Vitamin E is the most commonly supplemented antioxidant in horses. One study found that a single bout of submaximal exercise did not affect plasma α–tocopherol concentration, but horses conditioned for several weeks may require higher levels of vitamin E supplementation than routinely recommended (Siciliano et al 1996). Also, humoral immune response to vaccination was improved by supplementing horses 50 IU/kg dry matter per day as compared to a basal diet containing 18 IU/kg dry matter (Baalsrud & Overnes 1986).

Vitamin E intake was calculated in competitive endurance horses via a pre–ride nutritional survey detailing intake 2 weeks prior to the 80–km endurance race (Williams et al 2005). Horses were estimated to consume 1150 to 4700 IU/day of vitamin E in their total diet during this time period. This level is 1.2 to five times higher than the recommended levels given by the NRC (2007); which, for these animals estimated intake, averages 1000 IU/day. In this particular study a negative correlation was found between vitamin E intake and the activities of creatine kinase (CK) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and a positive correlation was found with intake and plasma α–tocopherol activity during the endurance ride (Williams et al 2005). These findings suggested that vitamin E intake may affect muscle membrane permeability and/or injury in horses during endurance exercise.

Safety

High dietary intake may interfere with the absorption of other fat–soluble vitamins such as vitamins A, D and K, although this has not been proven. Measures of oxidative stress were unchanged in horses supplemented with vitamin E at nearly 10 times the NRC (2007) recommended amount, but were found to have lower plasma β–carotene levels than both the control or moderately (5000 IU/day) supplemented group, which may indicate that vitamin E, has an inhibitory effect on β–carotene metabolism (Williams & Carlucci 2006).

Recommended dosage

For antioxidant effects, supplementation at 5 times the NRC (2007) minimum dietary inclusion, or about 5000 IU/day for an average 500 kg horse, is recommended. The vitamin E content of vegetable oils is variable and the vitamin is included to help stabilize the oil itself. Additional vitamin E is recommended to be added to the diet when including increased levels of vegetable oil. The author recommends ~150 IU/100 ml of added oil.

Vitamin C

Potential rationale for use

Vitamin C is another commonly added antioxidant, primarily included to help support respiratory health and immune function. Vitamin C scavenges antioxidant derived radicals and therefore can recycle or regenerate other components of the antioxidant system, particularly vitamin E (Chan 1993). Vitamin C is the primary antioxidant to neutrophil–derived oxidants in the lung and vitamin C concentrations in plasma as well as the epithelial lining fluid of the lungs have been shown to be reduced in horses with lung inflammation and in particular recurrent airway obstruction (RAO) (see Chapter 9). Under maintenance conditions horses have the ability to synthesize sufficient ascorbate, but the demand may increase as “stress” on the body is increased.

Data on efficacy

One study looking at the vitamin E and C interaction used 40 endurance horses competing in an 80–km race for the purpose of research (Williams et al 2004b). Plasma ascorbic acid concentrations were lower in the horses supplemented with vitamin E alone (5000 IU/day α–tocopheryl acetate) than those receiving the vitamin E plus C (same vitamin E dose, plus 7 g ascorbic acid/day) at rest. A study of polo ponies showed that throughout the polo season plasma α–tocopherol and ascorbic acid were higher in those given vitamin C in combination with vitamin E in the hard–working ponies, but this was not found with those in only light work or only supplemented with vitamin E (Hoffman et al 2001).

Recommended dosage

A recommended dosage for vitamin C is 10–20 mg/kg BW per day for high stress conditions, including prolonged transportation, exercise training, multiple days of competition, extreme climate changes, parturition, chronic separation from herd mates, or introduction to a new environment, where immune function may be decreased. For respiratory health, beneficial effects have been observed when vitamin C is provided at 9–10 mg/kg BW (Deaton et al 2004, Kirschvink et al 2002) as part of an antioxidant cocktail also including vitamin E (5 mg/kg BW; Deaton et al 2004).

Substances with no known nutritional requirement

Carnitine

Data on efficacy

Studies in horses have not confirmed that carnitine availability is rate–limiting during exercise. Horse skeletal muscle contains high levels of L–carnitine. Foster and Harris (1992) reported muscle carnitine concentrations between 18.5 and 26.9 mmol/kg dry muscle, with highest values observed in trained horses. Although L–carnitine is poorly absorbed, supplementation with 10–60 g/day did increase plasma but not muscle concentrations (Foster et al 1988, Harris et al 1995). Similar levels of supplementation (10 g/day) to 2–year–old trotters for 5 weeks of training and 15 weeks of detraining, however, were reported to increase the carnitine concentration in the gluteal muscle by 50%. The exercise–induced decrease in muscle glycogen and increase in blood lactate tended to be lower in the L–carnitine–supplemented horses (Harmeyer et al 2001). Other studies have also reported an apparently beneficial effect of feeding L–carnitine on the blood lactate response to exercise (Zeyner & Harmeyer 1999) but this finding has not been consistent. For example, feeding 9 and 12 g/day L–carnitine to young thoroughbred horses had no effect on post–exercise lactic acid and ammonia concentrations, nor CK/AST activities, although a faster return to basal values of lactic acid was reported (Falaschini & Trombetta 2001).

L–carnitine supplementation of young Standardbred horses (10 g/day) during conditioning was reported to increase the proportion of type IIA fibers in middle gluteal muscle (Rivero et al 2002) suggesting possible metabolic advantages. In a later study, however, no affect on training induced changes in heart rate or lactate during exercise or recovery were seen following 10 weeks of L–carnitine supplementation (10 g L–carnitine) in two year olds (Niemeyer et al 2005).

More recent work in humans has suggested that although carnitine supplementation may not affect performance per se, it might modulate markers of metabolic stress and mitigate muscle soreness (Spiering et al 2007) according to the authors by attenuating the “hypoxic chain of events leading to muscle damage after exercise”. This has not been explored to the author’s knowledge in horses.

Creatine

Potential rationale for use

Phosphocreatine provides a rapid but brief source of phosphate for the resynthesis of ATP during intensive exercise, acts as the “low ADP threshold sensor” as well as a buffer to ADP accumulation, and supports high-energy phosphate transfer. Recent reviews have concluded that creatine supplementation may exert benefits by: (1) influencing skeletal muscle directly through increasing muscle glycogen and phosphocreatine contents; (2) facilitating faster phosphocreatine resynthesis; (3) increasing expression of endocrine and growth factors mRNA; or (4) working indirectly through increased training volume (Rawson & Persky 2007, Safdar et al 2008).

Data on efficacy

Creatine is an amino acid derivative (methylguanidine–acetic acid) that occurs naturally in carnivorous diets. Horses, however, are likely reliant on synthesis from arginine, L-methionine and glycine. Creatine appears to be poorly absorbed from the intestinal tract in horses. A twofold increase in plasma concentration but no change in muscle content was observed when horses were fed 50 mg creatine/kg BW per day (Sewell & Harris 1995), a dose that results in a marked increase in muscle creatine content in man. Schuback et al (2000) also reported no change in muscle creatine content following creatine supplementation (100–120 mg/kg BW creatine monohydrate per day for 14 days), and observed no effect on performance parameters or muscle metabolic responses to exercise. A more recent study found no ultrasound changes in cross-sectional area and the thickness of the layer of fat of the longissimus dorsi muscle when 75 g of creatine monohydrate (about three-times that of the previous study by Sewel & Harris, 1995) was fed to Arabian horses for 90 days during aerobic training (Angelis et al 2007). Overall, there currently is no evidence to support the use of creatine as an ergogenic aid in horses.

Lipoic acid

Potential rationale for use

α-Lipoic acid (LA) and its reduced form, dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA), have received widespread attention as antioxidants with putative preventative and therapeutic implications for humans and experimental laboratory animals. α–Lipoic acid is an eight–carbon structure that contains a disulfide bond as a part of a dithiolane ring with a five–carbon tail. It is a cofactor in the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl CoA as part of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and also in α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (Reed et al 1951).

Lipoic acid is unique compared with other antioxidants because it is both water and fat soluble. It therefore can have activity in the cell membrane as well as in the cytoplasm. The carboxylic acid end allows it to be more water–soluble than tocopherol, and it contains more carbon atoms than ascorbic acid so it is more lipophilic (Biewenga et al 1997). Two sulfhydryl moieties allow for radical scavenging with both the reduced and oxidized form of LA (Dikalov et al 1997). Lipoic acid protects membranes by interacting with vitamin C and glutathione, which may also recycle vitamin E. Supplementing LA has found to be beneficial in a number of oxidative stress models, ischemia–reperfusion injury (Serbinova et al 1992), diabetes (Ziegler et al 1995), cataract formation (Maitra et al 1994), radiation injury (Ramakrishnan et al 1992), aging (Hagen et al 1999) and exercise (Khanna et al 1999).

Data on efficacy

Khanna et al (1999) compared rested and exercised rats supplemented with or without LA. The LA supplemented rats, both rested and exercised, had a higher glutathione (GSH) concentration, and a lower lipid peroxidation level measured by thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) as compared to non–supplemented rats. Aged rats supplemented with LA had a higher mitochondrial membrane potential, ambulatory activity, GSH and ascorbate concentration; furthermore, the malondialdehyde concentration was five times higher in the non–supplemented rats (Hagen et al 1999).

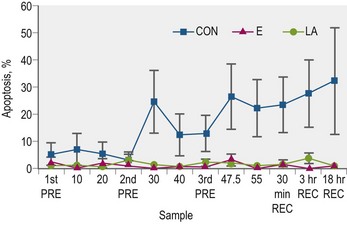

In trained Arabian horses, supplementation with either lipoic acid or vitamin E mitigated measures of white blood cell apoptosis during a simulated endurance exercise test (Williams et al 2004a; Fig. 19.3); although it should be noted that this was not a crossover study. Lipoic acid supplemented horses also had increased whole blood total GSH concentrations when compared to the control group (Williams et al 2004a) and increased plasma levels of ascorbic acid and α–tocopherol. Both the vitamin E and lipoic acid supplemented groups had about 40% more total GSH, 30% more α–tocopherol, and 15% more ascorbic acid than the control group. This illustrates the collaborative nature of the recycling and scavenging of antioxidant radicals as such increases were found using either vitamin E or lipoic acid.

Recommended dosage

A dose of 10 mg/kg BW/day DL-α-lipoic acid is the dose typically used in research studies (Williams et al 2002) without evidence of any adverse effects but has never been put into a commercial antioxidant supplement at this concentration due to its high cost and bitter taste.

Probiotics

Potential rationale for use

Probiotics were first defined as, “substances secreted by one organism that stimulates the growth of another” (Lilley & Stillwell, 1965). Later, the US Office of Regulatory Affairs of the FDA and AAFCO defined probiotics as “a source of live, naturally occurring microorganisms” (Yoon & Stern 1995) and which are now called “direct–fed microbials” (DFM). In the EU within the category “zootechnical additives”, the following functional group is included “ ‘gut flora stabilizers’: microorganisms or other chemically defined substances, which, when fed to animals, have a positive effect on the gut flora.” This would include probiotic bacteria as well as yeasts. Their use is directed at maintaining, enhancing or re-establishing “beneficial” bacteria and other microflora within the gastrointestinal tract. However, there has been no evidence to prove that providing probiotics to animals with healthy thriving GI flora will have any beneficial effect.

Data on efficacy

Studies have investigated if bacteria will survive transit through a horse’s GI system and shown that orally provided Lactobacillus rhamnosus bacteria will survive transit through a foal’s GI system and colonize the hindgut when fed at extremely high doses (Weese et al 2003). This group also showed that provision of Lactobacillus pentosus, a strain of bacteria isolated from the equine intestine, actually increases the severity of foal diarrhea, which raises concerns over the choice of bacteria in probiotics and/or the quality control of the probiotic used (Weese & Rousseau 2005). However, another study showed that providing five strains of Lactobacillus, also isolated from the equine intestine, did decrease the incidence of foal diarrhea (Yuyama et al 2004).

Yeast cultures have also been evaluated for their probiotic properties. Specifically after feeding horses Saccharomyces cerevisiae, viable yeast cells were found in the large intestine (Medina et al 2002), which indicates that yeast can survive transit through the GI track. It is theorized that yeast supplementation will increase the pH of the GI track and help improve fiber digestion (e.g., Morgan et al 2007, Jouany et al 2009). However, not all studies show a significant beneficial effect (Hall et al 1990) and it is hard to make a recommendation for its use in aiding fiber digestion in horses provided typical forage based rations. Although the use of Saccharomyces boulardi has been reported to significantly reduce the duration and severity of acute enterocolitis in one study in hospitalized horses (Desrochers et al 2005), much more work is needed to evaluate the potential for live yeast supplementation to help in cases of colic, laminitis and diarrhea.

Recommended dosage

Optimal dosages have not been determined; however, Weese (2001) gives a starting point of 1 × 109 to 1 × 1011 colony-forming units (cfu) per 50 kg BW per day, which was determined by extrapolation from human research.

Superoxide dismutase

Potential rationale for use

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is an enzymatic antioxidant, which catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide ions into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. A number of reports have indicated that supplementation with SOD may be effective in reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and inhibiting neutrophil infiltration to sites of tissue damage in several models of inflammation (Salvemini et al 1999, Masini et al 2002).

Data on efficacy

Although studies in rats (Radak et al 1995) and humans (Arent et al 2009, 2010a) have reported apparent beneficial effects with respect to exercise-associated oxidative stress and inflammation, limited research to date in horses has not demonstrated an effect of SOD supplementation on local (synovial fluid) or systemic markers of inflammation (Lamprecht & Williams 2012).

Complex materials that contain a mixture of putative active ingredients

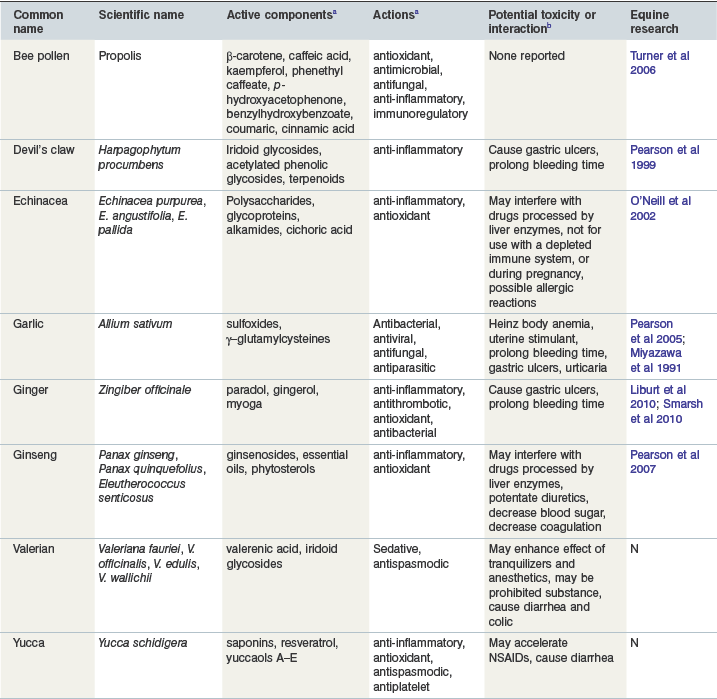

This group includes herbal supplements that contain active ingredients that are purported to affect the immune system among other various properties (antioxidant, anti–inflammatory, sedative, etc.). Some of these herbs can be classified as adaptogens, immunostimulants or both. Adaptogens increase resistance to stressors, physical, chemical or biological, whereas immunostimulants activate the nonspecific or innate defense mechanisms against viral, bacterial or cellular infections. Most of the studies to date in laboratory animals, humans and other species have determined that the immunologic effect of herbal supplements does not enhance normal immune response but may have beneficial effects if the immune system is compromised (Schulz et al 1998). A more recent reference suggests that very little scientific evidence is available for efficacy of herbal products use in humans, and only four of the top ten herbs in the United States have evidence based on randomized controlled trials (Bent & Ko 2004). Table 19-1 summarizes the active component, action, drug interactions, and equine research present for the major herbs described below.

Table 19-1 Herbal Supplements and other Functional Foods

a For references regarding ingredients or actions see text for the specific herb.

b Information compiled from Miller 1998, Poppenga 2001, Harman, 2002, Izzo et al 2005.

Reproduced with kind permission from Williams and Lamprecht (2008).

Bee pollen

Potential rationale for use

Bee pollen and propolis are similar resinous substances collected from various plant sources by honeybees. Propolis contains polyphenols and flavonoids, as well as several specific antioxidant compounds including beta-carotene, caffeic acid and kaempferol (Ahn et al 2004, Gomez-Caravaca et al 2006, Christov et al 2006). Reported biological properties include antioxidant, antimicrobial, antifungal, anti–inflammatory, and immunoregulatory actions (Liebelt & Calcagnetti 1999). Propolis with strong antioxidant activity was also found to have high total polyphenol content (Ahn et al 2004). Antimicrobial effects have been observed against Gram-positive bacteria and yeasts (Uzel et al 2005). Anti-inflammatory effects of propolis may involve nitric oxide inhibition (Tan–No et al 2006).