CHAPTER 158 Skin Grafting

Traumatic wounds are common in horses and can range from superficial abrasions requiring little or no care to those that are extremely labor intensive and expensive. Veterinarians play a critical role in the treatment of equine wounds and can provide pivotal guidance to owners regarding which wounds can be managed conservatively and which require immediate, aggressive veterinary care. The effects of this decision can mean the difference between a successful return to athletic soundness and chronic lameness or euthanasia. Wound management can be extremely rewarding. One of the key tools in achieving a successful outcome is the use of appropriate skin grafting techniques. Skin grafts provide functional and cosmetic coverage, stimulate wound contraction, and speed the overall healing process. The wounds that most commonly require grafting are large wounds on the body and those on the distal portions of the limb. Degloving wounds on the distal limb segments can be especially troublesome when trying to achieve a satisfactory outcome.

GRAFT PHYSIOLOGY

Initially during the adherence phase, grafts are held in place by fibrin that is exuded from the recipient site and receive temporary nutrition via passive diffusion from surrounding fluid, also known as plasmatic imbibition. Revascularization of the grafts begins 24 to 48 hours after grafting, and eventually the host vessels anastomose with vessels from the graft to supply nutrition, a process known as inosculation. In addition, revascularization of the graft is established by capillary buds from the recipient site invading the graft. By 3 to 4 days, fibroblasts have begun to invade the graft and form adhesions between the graft and recipient site, and by 9 to 10 days grafts are firmly attached via fibrous adhesions and functional vessels crossing the graft-host interface.

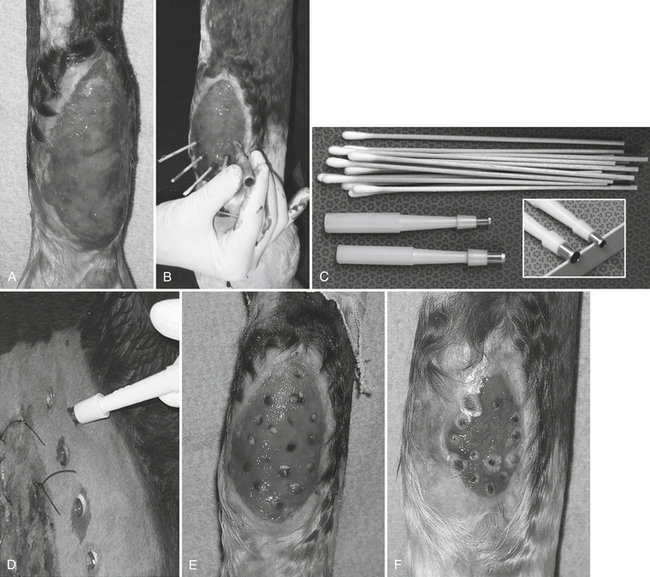

Pinch grafts initially appear as dark spots within the granulation bed approximately 1 to 2 weeks after grafting as the granulation tissue overlying the grafts sloughs. By 3 to 4 weeks after punch or pinch grafting, a ring of pink epithelium can be detected around the grafts, and by 42 to 56 days, hair begins to grow from the grafts. A 60% to 75% survival rate can be expected with either punch or pinch grafting; however, it is not uncommon to have greater than 90% graft survival. One major advantage of seed grafts is that the failure of one or several individual grafts does not translate to complete graft failure. Grafting a granulating wound stimulates contraction and epithelialization of the original wound (Figure 158-1),and this makes a significant contribution to the final outcome.

Figure 158-1 Granulating wound over the plantar aspect of the metatarsus undergoing a punch graft procedure. A, Recipient site before grafting, after having been trimmed once. Notice exudate accumulation on wound surface, protrusion above the level of the skin, and irregular surface. This wound is one trim away from being ready for punch grafts. B, Punch graft in progress with cotton-tip applicators in recipient sites and 4-mm skin biopsy punches being used to create holes. Notice that the wound bed is now level with the skin, is smooth, and deeper red, and that the wound has contracted significantly in the 7 days from the photo in A. C, Supplies for punch graft, including cotton-tip applicators and biopsy punches in two sizes. D, Harvest of the 6-mm punch grafts from the neck with both sutured and unsutured wounds. E, Punch grafts 1 day after grafting. F, Progression of wound healing 3 weeks after the grafting procedure. Notice the tremendous epithelial proliferation around the wound margin, the wound contracture, and the halos of new epithelium that are developing around the grafts. Several of the grafts were placed more deeply than was ideal within the wound and are therefore slower to begin to emerge. The wound has migrated from the midline around to the medial aspect of the limb, presumably as a result of the lines of tension in the area.