Chapter 3

Selected Infectious Agents

Evaluating cytologic samples often results in the observance of microorganisms, some of which may be primary etiologic agents, opportunistic secondary overgrowths, or part of the normal flora of the location sampled. In some cases, the challenge is not only the identification of the organisms but also the recognition of the significance or insignificance of the organism in the overall pathologic process. This chapter is intended to aid in recognizing selected organisms found during the cytologic evaluation of samples from dogs and cats. It is beyond the scope of this book and chapter to discuss all of the organisms noted in cats and dogs; however, this chapter is intended to serve as a reference for the more commonly encountered infectious agents in canine and feline cytopathology. Discussions of the pathologic changes and conditions that these organisms produce are found in the following relevant chapters. Sample collection, staining and submission of samples for culture were previously covered in Chapter 1.

Bacteria

Bacterial Cocci

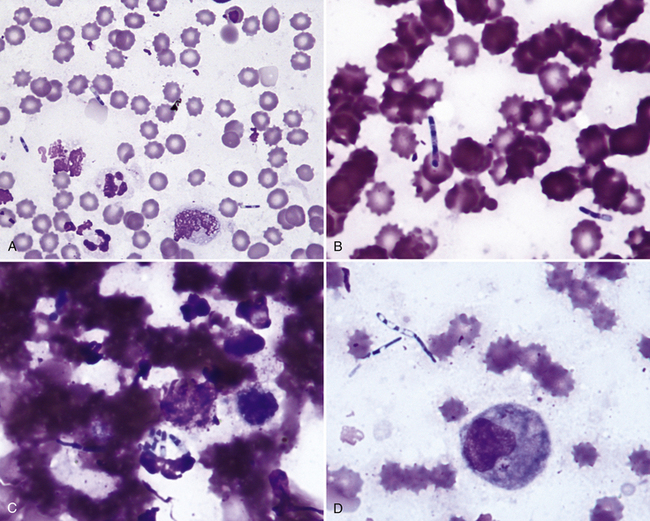

Pathogenic bacterial cocci are usually gram positive and of the genera Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, or Peptococcus (Figure 3-1). Staphylococci usually occur in clusters of 4 to 12 bacteria; however, Streptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, and Peptococcus spp. tend to occur in short or long chains of organisms. Staphylococcus and Streptococcus spp. are aerobic, and Peptostreptococcus and Peptococcus spp. are anaerobic. When cocci are identified in cytologic preparations, aerobic and anaerobic cultures and sensitivity testing should be performed to identify the organism and to guide optimal antibiotic therapy. As most cocci are gram positive, antibiotic therapy effective against gram-positive organisms should be used when it is deemed necessary to start therapy before culture and sensitivity results are received.

Figure 3-1 A, Neutrophilic inflammation with moderate numbers of bacterial cocci present both intracellularly and extracellularly. (Wright stain.) B, Higher magnification showing a neutrophil containing phagocytized bacterial cocci. (Wright stain.) C, Scattered red blood cells, two neutrophils, and a superficial squamous epithelial cell are shown. One of the neutrophils contains phagocytized bacterial cocci. (Wright stain.) D, Bacteria cocci chains. (Wright stain).

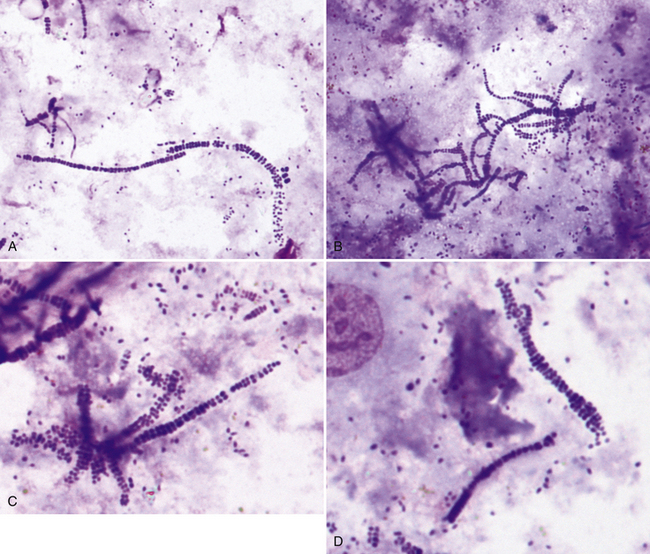

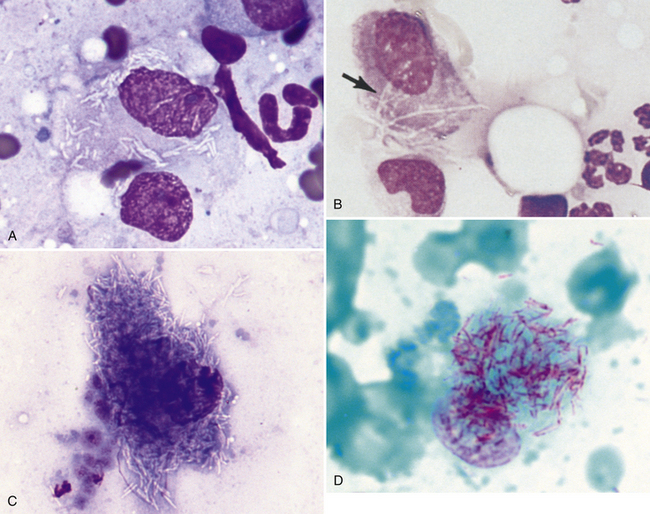

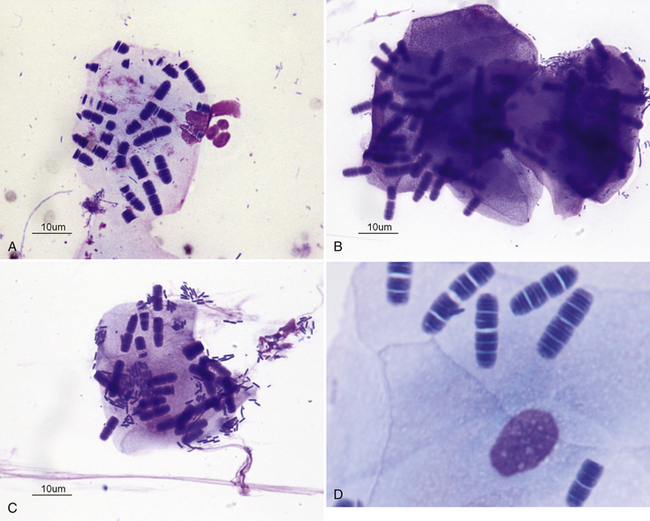

Dermatophilus congolensis replicates by transverse and longitudinal division, producing long chains of coccoid bacterial doublets that resemble small, blue railroad tracks (Figure 3-2). It infects the superficial epidermis, causing crusty lesions. Cytologic preparations from the undersurface of scabs from these crusty lesions are most rewarding in demonstrating organisms. The preparations usually contain mature epithelial cells, keratin bars, debris, and organisms. A few neutrophils may also be found.

Figure 3-2 A-D, Impression smear from skin lesions showing bacterial cocci replicating by transverse and longitudinal division, producing long chains of coccoid bacterial doublets that resemble small, blue railroad tracks. This pattern of bacterial cocci is typical of Dermatophilus congolensis. (Wright stain.).

Small Bacterial Rods

Most small bacterial rods are gram negative and some can be recognized as bipolar rods (Figure 3-3). It is safe to assume that all pathogenic, bipolar bacterial rods are gram negative. Common small bacterial rods include Escherichia coli and Pasteurella spp. Infections with bacterial rods are usually associated with a marked neutrophilic inflammatory response. When small bacterial rods are recognized in cytologic preparations, the lesion should be cultured to identify the organism, and sensitivity tests should be performed to determine the optimal antibiotic therapy. If it is necessary to institute antibiotic therapy before the culture and sensitivity results are received, the therapy employed should be effective against gram-negative organisms as most pathogenic small rods are gram negative.

Filamentous Rods

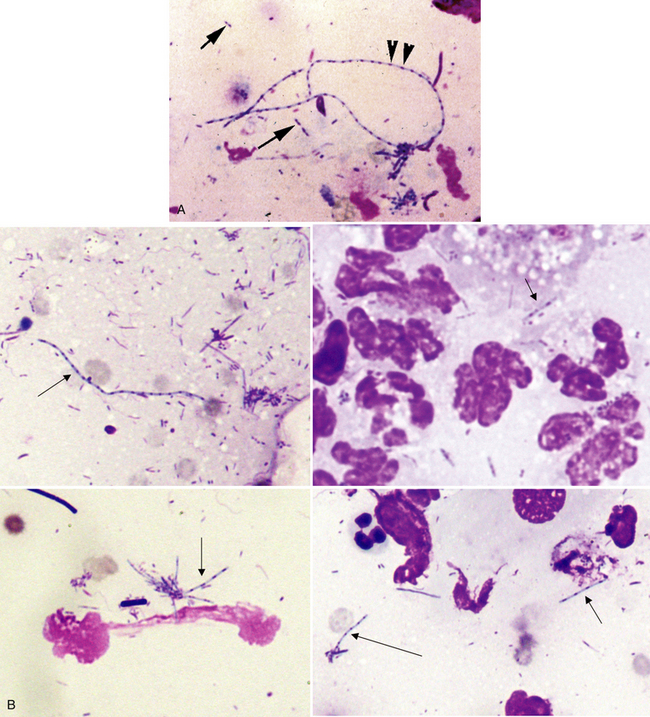

Pathogenic filamentous rods that cause cutaneous or subcutaneous lesions are typically Nocardia or Actinomyces spp. Other anaerobes such as Fusobacterium and Mycobacterium spp. may also be filamentous but are rarely so. Nocardia and Actinomyces spp. generally have a distinctive morphology in cytologic preparations stained with routine hematologic stains. They are characterized by long, slender (filamentous) strands that stain pale blue and have intermittent small pink or purple areas giving a “beaded” appearance to the organism (Figure 3-4). This morphology is characteristic of both Nocardia and Actinomyces spp. and the filamentous form of Fusobacterium spp. When these features are recognized cytologically, cultures should be performed specifically for Nocardia and Actinomyces spp. as well as for other anaerobes.

Figure 3-4 A, A long filamentous rod staining pale blue with intermittent small pink or purple dots (arrowheads) and smaller filamentous rods (arrows) are shown (Wright stain). B, Composite picture showing filamentous rods (arrows) typical of Actinomyces or Nocardia spp. (Wright stain.) C, Multiple filamentous rods and ruptured cells are shown. (Wright stain.)

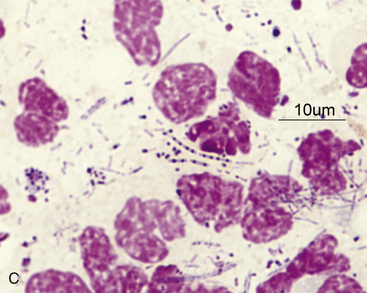

Mycobacterium spp. does not stain with routine hematologic stains. As a result, negative staining rods (Figure 3-5) may be observed in the cytoplasm of macrophages, inflammatory giant cells, or both. When epithelioid macrophages, inflammatory giant cells, or both are encountered in cytologic preparations that do not contain any obvious organisms, a careful search for negative images of Mycobacterium spp. should be made. Mycobacterium spp. stain with acid-fast stains; therefore, when the character of the lesion suggests that Mycobacterium spp. be considered, and negative images are not identified, an acid-fast stain can be performed to aid in organism identification (see Figure 3-5, C). Cultures, and/or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of tissue samples for Mycobacterium spp. may be helpful. Specific breeds of cats and dogs, including Siamese cats, Bassett dogs, and Miniature Schnauzer dogs, appear to be predisposed to Mycobacterium infections.

Figure 3-5 A, Negative images of Mycobacterium organisms in macrophage from cat liver aspirate (Wright stain). B, Fine-needle aspirate of a consolidated pulmonary mass. An alveolar macrophage, which contains nonstaining bacterial rods identified as clear streaks through the cell (arrow), is indicative of a Mycobacterium infection. (Wright stain.) C, Cat liver Mycobacterium (Wright stain). D, Cat liver Mycobacterium. (Acid-fast stain.)

Large Bacterial Rods

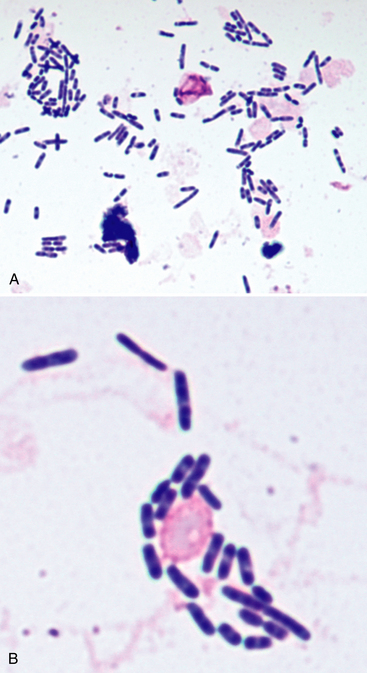

Large bacterial rods that are pathogenic and sometimes infect the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues include Clostridia spp., and infrequently, Bacillus spp. When large bacterial rods are thought to be pathogenic, both aerobic and anaerobic cultures should be performed. Also, the smears should be inspected for large rods containing spores (Figure 3-6), as this may indicate Clostridium spp. infection.

Figure 3-6 A, Scattered inflammatory cells, red blood cells (RBCs), and large spore-forming bacterial rods typical of Clostridium spp. (Wright stain.) B, Higher-power view from same case as in A. Scattered RBCs and two large extracellular spore-forming bacterial rods are shown. (Wright stain.) C, Same case as in A. Multiple phagocytized spore-forming bacterial rods are shown. (Wright stain.) D, Clostridium organisms from mass on dog (Wright stain).

Occasionally, the large nonpathogenic bacterial rods of Simonsiella spp. are observed in cytologic specimens (e.g., contaminated tracheal washes). Simonsiella spp. are part of the normal oral flora of many domestic species and divide lengthwise, yielding parallel rows of bacteria that give the impression of a single, large bacterium with the characteristic “footprint” (Figure 3-7). Finding these organisms in cytologic samples from various locations indicates oral contamination; for example, if found in nasal flush samples, it may indicate a nasal–oral fistula, or if found in a lesion on a limb, it indicates licking and potentially could complicate the interpretation of an atypical mesenchymal population as neoplastic versus reactive.

Figure 3-7 A, Superficial squamous epithelial cell with adherent bacteria. Simonsiella organisms are large striated rodlike organisms. Other bacteria are present, adhered to the squamous cell and free in the background of the smear. (Wright stain.) B, Two superficial squamous epithelial cells with many Simonsiella organisms. (Wright stain.) C, One superficial squamous epithelial cell with many Simonsiella organisms and bacterial rods. (Wright stain.) D, Higher magnification, Simonsiella organisms (Wright stain).

Yeast, Dermatophytes, Hyphating Fungi, and Algae

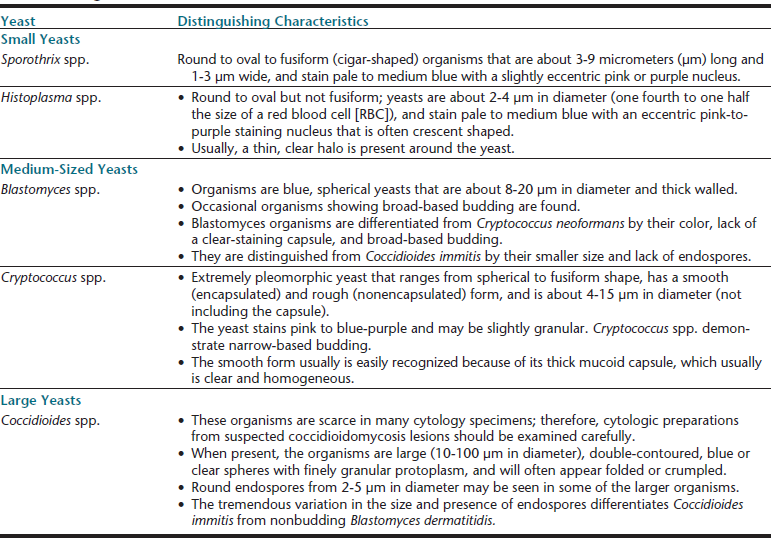

Mycotic agents produce lesions that tend to be more granulomatous; that is, the inflammatory reaction has more macrophages compared with bacterial lesions. However, neutrophils may still be the predominant cell type, and eosinophils may be plentiful with certain hyphating fungi. Mycotic lesions often contain low numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibroblasts, and smaller organisms that tend to be phagocytized by macrophages, but can be found phagocytized by granulocytic cells as well. Many factors, including the infectious agent, the animal demographics, the location of the lesion, the chronicity of the lesion, and the immune status of the animal, will influence the nature of the lesion in these infections. A comparison of the common fungi that form yeasts in tissues is presented in Table 3-1.

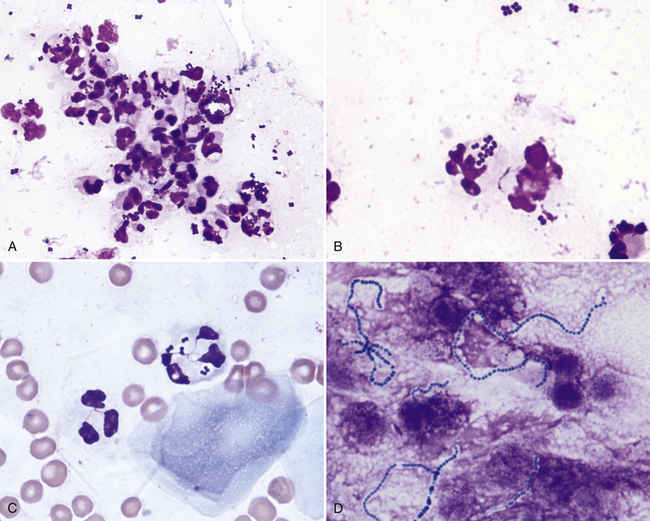

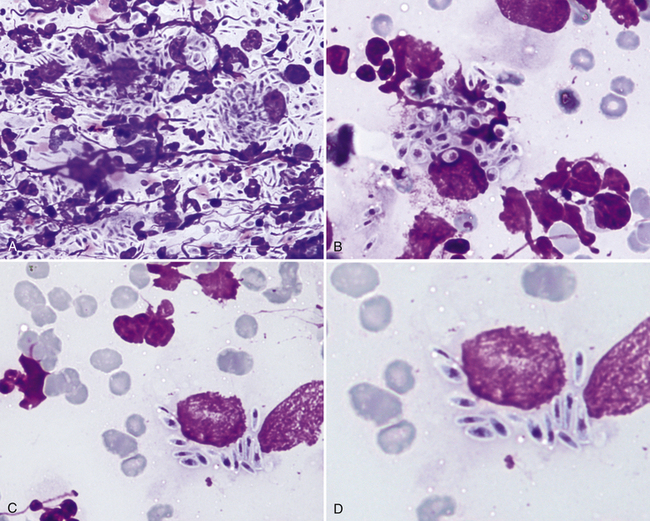

Sporothrix schenckii

In cytologic preparations stained with hematologic stains, S. schenckii (Figure 3-8) are round to oval shaped or fusiform (cigar shaped), 3 to 9 micrometers (µm) long and 1 to 3 µm wide and stain pale to medium blue with a slightly eccentric pink or purple nucleus. Caution in interpreting is warranted, as occasionally these organisms can be confused with Histoplasma capsulatum if only a few yeasts are found and if they are not classically fusiform.

Figure 3-8 A, Scraping from a skin lesion in a cat. Pyogranulomatous inflammation and high numbers of sporotrichosis organisms are present in the smear. (Wright stain.) B, Macrophage containing round, oval, and fusiform sporotrichosis organisms. (Wright stain.) C, A ruptured macrophage containing many fusiform sporotrichosis organisms. (Wright stain.) D, Higher magnification, Sporothrix organisms in cat. (Wright stain).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree