Chapter 162 Sedation of the Critically ill Patient

PATIENT EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

On presentation, immediate attention should be paid to the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation; see Chapter 2, Patient Triage). These should be deemed adequate before proceeding. Evaluation of neurologic status, including mental status and evidence of spinal cord or head trauma, should be included. A complete history should be obtained if possible, including presenting complaint, known medical conditions, any current medications, and previous anesthesia history.

Cardiac arrhythmias, especially premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), are seen commonly in critically ill patients, including those with gastric dilation-volvulus, hemoabdomen, and/or thoracic trauma. In addition, they can occur secondary to electrolyte abnormalities, hypoxemia, or hypercarbia. The type and significance of arrhythmias should be determined and the underlying cause treated, if possible. Indications for antiarrhythmic therapy before drug administration include frequent multiform PVCs or paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia that adversely affects blood pressure (see Chapter 47, Ventricular Tachyarrhythmias).

When time and the animal’s condition permit, electrolyte abnormalities should be normalized before drug administration. Severe hyperkalemia (potassium >6 mmol/L) is seen frequently in patients with renal compromise, urinary tract obstruction or rupture, massive tissue trauma, or severe dehydration with metabolic acidosis (see Chapter 55, Potassium Disorders). Drug administration in a patient with hyperkalemia is associated with a high incidence of arrhythmias and cardiac arrest, and therefore appropriate treatment should be instituted before proceeding. Hypocalcemia may be seen transiently after citrated blood product administration, although this generally self-resolves.

CHOICE OF AGENT

The choice of sedative agent will depend on the patient’s current physical status, reason for presentation, pertinent history, and the procedure to be performed. Special attention should be paid to both cardiovascular and respiratory effects of these agents, but contraindications to drug use should also be considered. Intravenous administration allows for titration of the drugs and is generally preferred. Intramuscular sedation may be helpful, especially in the fractious patient or one with severe respiratory distress that becomes easily stressed with restraint. A complete list of commonly used sedative drugs can be found in Table 162-1.

Table 162-1 Commonly Used Sedative Drug Dosages

| Drug | Dosage (mg/kg) | Route |

|---|---|---|

| Anticholinergic Agents | ||

| Atropine | 0.02 | IM, SC |

| 0.01 | IV | |

| Glycopyrrolate | 0.01 | IM |

| 0.005 | IV | |

| Sedatives and Tranquilizers | ||

| Acepromazine | 0.005 to 0.1 | IM, IV, SC |

| Diazepam | 0.2 to 0.5 | IM, IV |

| Midazolam | 0.1 to 0.5 | IM, IV |

| Flumazenil (reversal agent) | 0.01 to 0.02 | IV |

| Medetomidine | 0.001 to 0.03 | IM |

| Atipamezole (reversal agent) | 0.1 to 0.25 | IV, IM |

| Opioid Agonists and Partial Agonists | ||

| Buprenorphine | 0.005 to 0.02 | IM, IV |

| Butorphanol | 0.1 to 0.5 | IV |

| 0.2 to 0.5 | IM | |

| Fentanyl | 0.025 to 0.01 | IV |

| Hydromorphone | 0.05 to 0.2 (½ dose in cats) | IM, IV |

| Morphine | 0.2 to 2 (½ dose in cats) | IM, IV |

| Methadone | 0.1 to 0.5 (½ dose in cats) 0.2 to 2.0 (½ dose in cats) | IV SC, IM |

| Nalbuphine | 0.1 to 2.0 | IM, IV |

| Oxymorphone | 0.02 to 0.2 (½ dose in cats) | IM, IV |

| Naloxone | 0.01 to 0.04 | IV, IM (reversal agent) |

| Other Agents | ||

| Ketamine | 2 to 8 (cat only) | IM |

| 2 to 5 | IV | |

| Telazol | 2 to 4 | IM (may have prolonged recovery) |

| Propofol | 1 to 6 | IV (titrate slowly to effect) |

IM, Intramuscular; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous.

Opioids

Most sedative techniques in the critically ill patient involve a sedative or tranquilizer in combination with an opioid analgesic (see Chapter 184, Narcotic Agonists and Antagonists). This neuroleptanalgesic combination generally produces a greater degree of sedation and analgesia with less cardiovascular depression than that achieved by comparable doses of either drug alone.

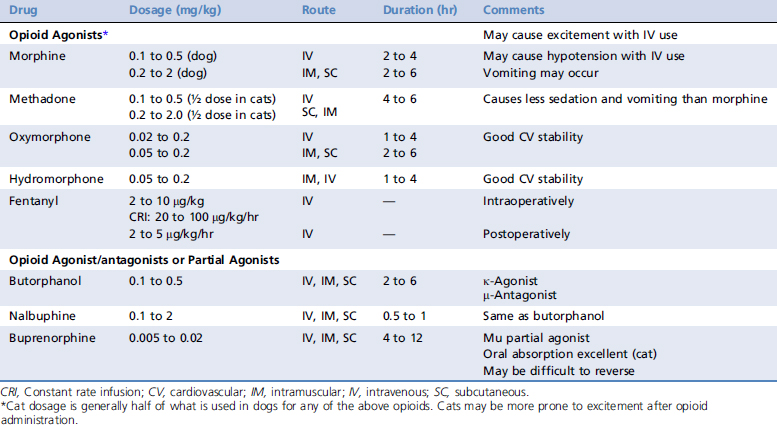

Before administering an opioid (or any other drug), the veterinarian should carefully observe the animal and consider the underlying disease process. Commonly used opioid drugs and their pertinent information can be found in Table 162-2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree