45 Secondary canine glaucoma

CASE HISTORY

Many dogs will have a history of previous ocular disease, although this is not always the case, and the dog might not have received veterinary treatment despite the owner being aware that there was something ‘not quite right’ with the eye for a while before it became red and painful. The most frequent previous ocular problem will be anterior uveitis – traumatic, immune-mediated or infectious – which responded to treatment initially but on cessation of anti-uveitis medication the eye deteriorated again a few days or weeks later. Sometimes owners will have restarted the previously prescribed medication but this did not improve the eye and so they returned for another examination. The cases with an acute history might be associated with lens luxation, so this should be considered in all terrier breeds (see Chapter 33 on uveitis and Chapter 42 on lens luxation).

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

On general clinical examination the dog might be slightly depressed with a mild pyrexia. It might be head shy and resent examination of the affected eye. A thorough general examination should be undertaken since the ocular problems might be associated with systemic disease (see Chapter 33). The presentation is normally unilateral for secondary glaucoma, but if a bilateral uveitis has been present, then both eyes can develop secondary glaucoma more or less simultaneously.

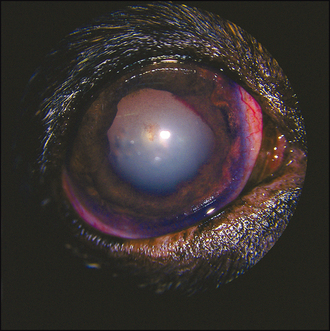

On ocular examination the affected eye might be noticeably enlarged. This is more common in long-standing cases or in younger dogs and puppies where the globe is able to stretch more easily (see Figure 37.5). The eye is likely to be red, with conjunctival hyperaemia and episcleral congestion; some peripheral corneal vascularization (ciliary flush) is also likely to be present. The eye is probably blind with no menace response, and the pupil is normally dilated and unresponsive, although if a previous uveitis has been present the pupil might be miotic, especially if extensive posterior synechiae are present. Alternatively, the pupil might be misshapen (dyscoria) (Figure 45.1). Thus the actual size of the pupil is not always useful in assisting with the diagnosis of secondary glaucoma.

The cornea will not be normal. Some corneal oedema is likely, giving a steamy appearance, such that detailed intraocular examination might be difficult. Corneal vascularization, pigmentation and ulceration are all possible (often associated with exposure keratitis). In addition, corneal striae (Haab’s striae; see Figure 44.4) might be present. These appear as a double white line on the cornea, almost like narrow train tracks, and are due to breaks in Descemet’s membrane which form as the globe stretches. If there is any ongoing uveitis, this might manifest as aqueous flare, hypopyon or hyphaema.